Buckle Up Your Seatbelt and Behave

Do we take more risks when we feel safe? Fifty years after we began using the three-point seatbelt, there’s a new answer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/speeding-car-highway-safety-seat-belt-631.jpg)

In the middle of the last century, Volvo began seeking improvements to seat belts to protect drivers and passengers in its vehicles. When the Swedish automaker tried a single strap over the belly, the result was abdominal injuries in high-speed crashes. The engineers also experimented with a diagonal chest restraint. It decapitated crash-test dummies.

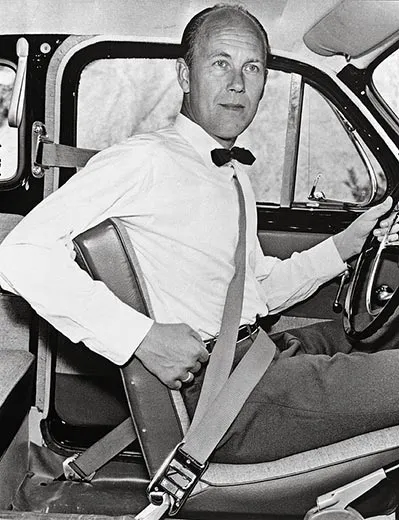

Volvo then turned to a 38-year-old mechanical engineer named Nils Bohlin, who had developed pilot ejector seats for the Saab aircraft company. Bohlin knew it would not be easy to transfer aerospace technology to the automobile. "The pilots I worked with in the aerospace industry were willing to put on almost anything to keep them safe in case of a crash," he told an interviewer shortly before he died, in 2002, "but regular people in cars don't want to be uncomfortable even for a minute."

After a year's research and experimentation, Bohlin had a breakthrough: one strap across the chest, another across the hips, each anchored at the same point. It was so simple that a driver or passenger could buckle up with one hand. Volvo introduced the result—possibly the most effective safety device ever invented—50 years ago; other automakers followed suit. No one can tally exactly how many lives Bohlin's three-point seat belt has spared, but the consensus among safety experts is at least a million. Millions more have been spared life-altering injuries.

But before we break out the champagne substitute to honor the three-point seat belt's demi-centennial, we might also consider the possibility that some drivers have caused accidents precisely because they were wearing seat belts.

This counterintuitive idea was introduced in academic circles several years ago and is broadly accepted today. The concept is that humans have an inborn tolerance for risk—meaning that as safety features are added to vehicles and roads, drivers feel less vulnerable and tend to take more chances. The feeling of greater security tempts us to be more reckless. Behavioral scientists call it "risk compensation."

The principle was observed long before it was named. Soon after the first gasoline-powered horseless carriages appeared on English roadways, the secretary of the national Motor Union of Great Britain and Ireland suggested that all those who owned property along the kingdom's roadways trim their hedges to make it easier for drivers to see. In response, a retired army colonel named Willoughby Verner fired off a letter to the editor of the Times of London, which printed it on July 13, 1908.

"Before any of your readers may be induced to cut their hedges as suggested by the secretary of the Motor Union they may like to know my experience of having done so," Verner wrote. "Four years ago I cut down the hedges and shrubs to a height of 4ft for 30 yards back from the dangerous crossing in this hamlet. The results were twofold: the following summer my garden was smothered with dust caused by fast-driven cars, and the average pace of the passing cars was considerably increased. This was bad enough, but when the culprits secured by the police pleaded that ‘it was perfectly safe to go fast' because ‘they could see well at the corner,' I realised that I had made a mistake." He added that he had since let his hedges and shrubs grow back.

Despite the colonel's prescience, risk compensation went largely unstudied until 1975, when Sam Peltzman, a University of Chicago economist, published an analysis of federal auto-safety standards imposed in the late 1960s. Peltzman concluded that while the standards had saved the lives of some vehicle occupants, they had also led to the deaths of pedestrians, cyclists and other non-occupants. John Adams of University College London studied the impact of seat belts and reached a similar conclusion, which he published in 1981: there was no overall decrease in highway fatalities.

There has been a lively debate over risk compensation ever since, but today the issue is not whether it exists, but the degree to which it does. The phenomenon has been observed well beyond the highway—in the workplace, on the playing field, at home, in the air. Researchers have found that improved parachute rip cords did not reduce the number of sky-diving accidents; overconfident sky divers hit the silk too late. The number of flooding deaths in the United States has hardly changed in 100 years despite the construction of stronger levees in flood plains; people moved onto the flood plains, in part because of subsidized flood insurance and federal disaster relief. Studies suggest that workers who wear back-support belts try to lift heavier loads and that children who wear protective sports equipment engage in rougher play. Forest rangers say wilderness hikers take greater risks if they know that a trained rescue squad is on call. Public health officials cite evidence that enhanced HIV treatment can lead to riskier sexual behavior.

All of capitalism runs on risk, of course, and it may be in this arena that risk compensation has manifested itself most calamitously of late. William D. Cohan, author of House of Cards, a book about the fall of Bear Stearns, speaks for many when he observes that "Wall Street bankers took the risks they did because they got paid millions to do so and because they knew there would be few negative consequences for them personally if things failed to work out. In other words, the benefit of their risk-taking was all theirs and the consequences of their risk-taking would fall on the bank's shareholders." (Meanwhile investors, as James Surowiecki noted in a recent New Yorker column, tend to underestimate their chances of losing their shirts.) Late last year, 200 economists—including Sam Peltzman, who is now professor emeritus at Chicago—petitioned Congress not to pass its $700 billion plan to rescue the nation's overextended banking system in order to preserve some balance between risk, reward and responsibility. Around the same time, columnist George Will pushed the leaders of the Big Three automakers into the same risk pool.

"Suppose that in 1979 the government had not engineered the first bailout of Chrysler," Will wrote. "Might there have been a more sober approach to risk throughout corporate America?"

Now researchers are positing a risk compensation corollary: humans don't merely tolerate risk, they seek it; each of us has an innate tolerance level of risk, and in any given situation we will act to reduce—or increase—the perceived risk, depending on that level.

The author and principal proponent of this idea is Gerald J.S. Wilde, professor emeritus of psychology at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario. In naming his theory "risk homeostasis," Wilde borrowed the word used for the way we humans, without knowing it, regulate our body temperature and other functions. "People alter their behavior in response to the implementation of health and safety measures," Wilde argued in his 1994 book, Target Risk. "But the riskiness of the way they behave will not change, unless those measures are capable of motivating people to alter the amount of risk they are willing to incur." Or, to make people behave more safely, you have to reset their risk thermostats.

That, he says, can be done by rewarding safe behavior. He notes that when California promised free driver's-license renewals for crash-free drivers, accidents went down. When Norway offered insurance refunds to crash-free younger drivers, they had fewer accidents. So did German truck drivers after their employers offered them bonuses for accident-free driving. Studies indicate that people are more likely to stop smoking if doing so will result in lower health and life insurance premiums.

Wilde's idea remains hotly disputed, not least by members of the auto-safety establishment. "Wilde would have us believe that if you acquire a brand-new car with air bags, you will decide to drive your new car with more reckless abandon than your old one," says Anne McCartt, a senior vice president for the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, a nonprofit organization funded by auto insurers. "You will be unconcerned that your more reckless driving behavior will increase the chances of crashing and damaging your new car because returning to your previous level of injury risk is what you really crave! Only abstract theoreticians could believe people actually behave this way."

Still, even the institute acknowledges that drivers do compensate for risk to some degree, particularly when a safety feature is immediately obvious to the driver, as with anti-lock brakes. But seat belts? No way, says McCartt.

"We've done a number of studies and did not find any evidence" that drivers change their behavior while wearing them.

Questions over risk compensation will remain unresolved because behavioral change is multidimensional and difficult to measure. But it is clear that to risk is human. One reason Homo sapiens rules the earth is that we are one of history's most daring animals. So how, then, should we mark the 50th anniversary of the seat belt?

By buckling up, of course. And by keeping in mind some advice offered by Tom Vanderbilt in Traffic: Why We Drive the Way We Do (and What It Says About Us): "When a situation feels dangerous to you, it's probably more safe than you know; when a situation feels safe, that is precisely when you should feel on guard." Those are words even the parachutists, wilderness hikers and investors among us can live by.

William Ecenbarger is a former contributing editor for Reader's Digest.