Beach Tourists Who Collect Shells May Be Harming the Environment

At one beach in Spain, increasing numbers of tourists have caused a 60 percent decline in shell abundance, potentially disrupting the aquatic ecosystem

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9e/1c/9e1c9973-6c95-4429-a169-6cfc7f985436/0000-shell.jpg)

Walking along the seashore in search of shells and other curios is a favorite pastime for beachgoers of all ages. When those whimsical walkers pocket the nautical treasures they find on the beach, however, there can be unintended environmental repercussions. Shells provide a diverse swath of environmental functions: they help to stabilize beaches and anchor seagrass; they provide homes for creatures such as hermit crabs and hiding places for small fish; they are used by shorebirds to build nests; and when they break down, they provide nutrients for the organisms living in the sand or for thsoe that build their own shells.

According to new research published in PLoS One, seemingly innocent shell collecting may be having an impact on these environmental functions. As tourism increases at a beach, researchers found, the number of shells found there, in turn, decreases. This might lead to a decline in beach health. This study did not explore those potential detrimental environmental impacts caused by missing shells, but the authors think the habitat changes might be "multiple," including increased beach erosion, a decline in calcium carbonate from recycled shells and a drop in diversity and abundance of animals and plants that depend on shells, such as crabs, small fishes, algae and seagrass.

Although the environmental implications surrounding vanishing shells are serious, until now, no one has evaluated the examined the extent to which shells are disappearing. “The removal of dead shell remains by tourists represents one of the most understudied and least understood processes associated with human activities along marine shorelines,” the study authors, who are from the University of Florida and the University of Barcelona, write.

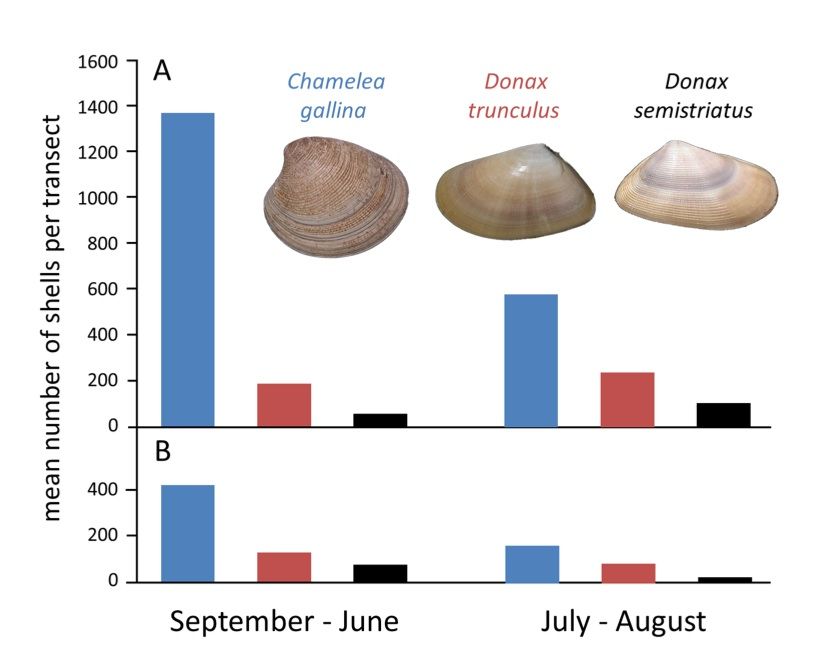

To see whether tourists really are having an effect on shell abundance, the researchers undertook a case study of Llarga beach in Spain, where they first began recording shell occurrence back in 1978. The study involved two survey periods, one from 1978 to 1981 and another from 2008 to 2010. During these years, the researchers combed the beach once a month, recording any shells or shell pieces they found on transect walks.

Over the last three decades, Llarga beach has remained surprisingly underdeveloped, with no new commercial fisheries or urban sprawl popping up. Tourism, however, has increased. Based on hotel data, the authors gleaned that the number of tourists vacationing in Llarga beach—mostly in the summer—has tripled since 1978.

The number of shells found on the beach decreased by 60 percent since 1978, the authors found. During those first transects, they turned up an average of about 1,500 shells per walk, whereas just 580 appeared on those same walks conducted 30 years later. Moreover, they found a “remarkable congruence” for the timing of shell disappearance; most shells went missing over the summer months when tourism was at its peak, whereas shells replenished and stayed put on the beach over the winter months. Weather, currents and wave action have not changed over the years, ruling out the possibility that nature rather than people was responsible for the waning shells.

While this study represents just one location in the world, the authors point out that Llarga beach isn’t a particularly hot travel destination, and that the shells found there aren’t especially beautiful. “If a relationship between increased tourism and accelerated shell removal can be detected at a place that is not famous for its shells, it is likely that beaches known for their shells and frequented by collectors have had more substantial impact,” the authors postulate. Figuring out what, if anything, that impact is will require further studies.

For places with high tourism traffic or those that house especially rare or beautiful shells, it might make sense to create laws stipulating how many shells a person may be remove from a beach, they suggest. For example, they point out that the Bahamas already has rules in place about the number of shells tourists can remove from the country.

For other, more low-key places such as Llarga beach, however, a public education campaign might be a better strategy for discouraging shell removal. Much as national parks encourage visitors not to pick wildflowers or remove animals in their “Leave No Trace” program, beaches, too, could spread the word that sunset walks are better recorded in memory, poem or photograph than in shell souvenirs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)