Are Modern Football Helmets Any Safer than Old-School Leather Ones?

Recent testing shows that, contrary to prior findings, new plastic helmets reduce the risk of concussions by 45 to 96 percent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130507091204helmet-comparison-small.jpg)

In the past century or so, football helmets have come a long way, evolving from crude “leatherheads” crafted by shoemakers to plastic-and-rubber hybrids that can be customized to fit a player’s head and have radios built in.

Nevertheless, the sport currently faces a serious and growing problem: brain injuries. Studies have shown that former NFL players are about three times more likely to die from Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Lou Gehrig’s diseases as the general population, a result of the alarming number of concussions they experience over the course of their careers. The NFL has responded by changing its rules to minimize head impacts, instituting stricter guidelines for concussed players returning to games and pouring money into attempts to develop safer helmets.

But some critics argue that, no matter how much research we undertake, there’s simply no way to create a concussion-proof helmet—no technology can stop a fundamentally violent game from inflicting harm. A 2011 study, in fact, found that with many types of impacts, modern helmets were no better than vintage leather ones at protecting players’ heads.

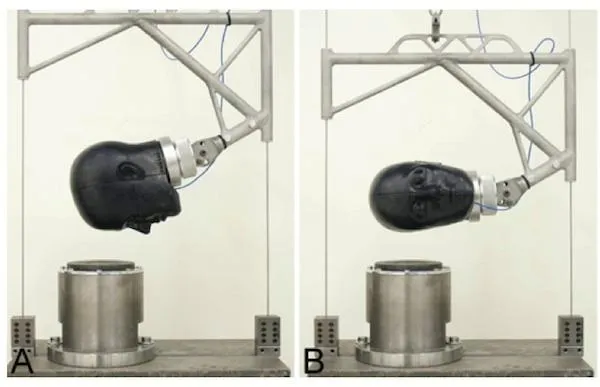

But now, fans who find their desire for a safe game at odds with their love of it can take comfort in a new study, published today in the Journal of Neurosurgery, that determines otherwise: Compared to “leatherheads,” new helmets are indeed much more effective at protecting the human head. Researchers from Virginia Tech came to the finding by using an automated head impact simulation system to test the effectiveness of a pair of vintage Hutch H-18 leather helmets from the 1930s against 10 plastic helmets currently in use, and found that, depending on the force of impact, modern helmets reduced the concussion risk by anywhere from 45 to 96 percent.

The team used the system to measure four different types of head impacts (on the front, side, rear and top of the head), and dropped the head from a range of heights (12, 24, 36, 48 and 60 inches) with each helmet on to simulate in-game impacts of a variety of intensities. Sensors inside the head were used to measure the force of each type of impact. This same type of testing, developed by the Virginia Tech team, has been used extensively to classify the safety of modern helmets on a 1 through 5-star scale.

The researchers found that there was some difference in the performance of the modern helmets—but, as you’d probably expect just from looking at them, the vintage leather helmets performed significantly more poorly than any of the plastic ones. At the lowest intensity impacts (from a 12 inch drop height), the modern helmets reduced the impact on the head by by 59 to 63 percent, and at the medium-intensity impacts (from 36 inches), they provided a 67 to 73 percent reduction. The researchers didn’t even try dropping the head with the leather helmets on from 48 or 60 inches for fear of damaging them.

At the same time, it’s worth noting that the vintage helmets tested were each about 80 years old, so their age might have meant weaker leather fibers than if pristine leatherheads had been tested. Additionally, the leather helmets had presumably taken some beating during their years of use, while the plastic ones were unused before being subjected to the drops, which might have further skewed the results.

Still, both these factors were also included in the previous 2011 finding that leather helmets were just as effective as modern ones—so what accounts for the fact that this experiment so thoroughly contradicted it? The authors of this study say that the experimental setup used in the previous one—in which two helmeted heads were smashed together, one with a modern helmet and the other with either a modern or leather one—distorted the findings and masked the differences between helmet types. Some of the impact, they say, was actually absorbed by the padding in the modern plastic helmet even when the leather one was being tested.

Of course, given the distressing numbers on the concussions suffered by football players even with the latest helmets, this sort of testing shouldn’t suggest that the goal of designing safer head gear has been achieved. But it should give us a bit of hope in showing that 100 years of helmet design has provided some benefits—and future efforts to create and rigorously test new helmet technologies might be able to cut down on concussions long-term.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)