Apples of Your Eye

Fruit sleuths and nursery owners are fighting to save our nation’s apple heritage…before it’s too late

Sixteen years ago, when I worked at The Planters & Designers garden center in Bristol, Virginia, old-timers frequentlycame in and asked for apple varieties called Virginia Beauty and Yellow Transparent. I tried to look them up infruit tree catalogs, but I could never find them. The more they asked me, the more intrigued I became. Though I came from along line of nursery men, I knew little about fruit varieties ofthe past, a subject called historical pomology.

Of course, that was before Henry Morton drove into the gravel parking lot at the garden center in the spring of 1988. He was wearing blue jeans and a button-downshirt; I figured he was a customer who had come to buy a rose bush and a bag of manure and be on his way. But Morton, a Baptist preacher from Gatlinburg, Tennessee, slapped me on the back, cornered me in the blue rug junipers and proceeded to try to sell me a Limbertwig. A Limbertwig?

"Limbertwigs vary in size, shape, color, quality and tree habit," said Morton, "but they all have one distinguishing characteristic, and that is their distinct Limbertwig flavor." I must have looked puzzled, so he told me that a Limbertwig was an old-fashioned apple.

It turns out that Mr. Morton spread not only the Gospel but some of the best-tasting apple varieties ever grown, many of them old lines or antique cultivars, rescued from the edge of extinction—varieties such as Moyer's Spice, Walker's Pippin, Sweet Bough, and Black Limbertwig. His 11- by 17-inch price list named some 150 varieties—including the Virginia Beauty ($5 for a five-foottree) and the Yellow Transparent ($5). Our meeting was the beginning of a friendship that would add some poetry to my rootball-toting life. For I would taste these mouthwatering apples at Morton's hillside nursery, and learn that the dark red, nearly black, Virginia Beauty is one of the best late keepers (apple parlance for a variety that ripens late and keeps well into the winter) you could ever sink your teeth into: sweet and juicy, with hints of cherry and almond. Yellow Transparent, also called June Apple, is almost white when fully ripe. Its light flesh cooks up in about five minutes and makes exquisite buttermilk biscuits. Once I'd sampled these old varieties, a Red Delicious or a Granny Smith never bore a second look.

Largely because of Morton, in 1992 my wife and I opened a small mail-order nursery that specializes in antique apple trees in general and old Southern apples in particular. We started buying stock wholesale from Morton and then reselling the trees. Not surprisingly, Virginia Beauty becameone of our biggest hits.

Along the way I discovered the sheer magnitude of America's long love affair with the apple. Today, only 15 popular varieties account for more than 90 percent of U.S.production. That wasn't always so. By 1930, Southerners alone had developed nearly 1,400 unique apple varieties, while more than 10,000 flourished nationwide. They came warts and all, some with rough, knobby skin, others as misshapen as a potato, and they ranged from the size of cherries to nearly as big as a grapefruit, with colors running the entire spectrum—flushed, striped, splashed and dottedin a wonderful array of impressionistic patterns.

Sadly, more than a thousand of these old Southern varieties are thought to be extinct. But Morton, who died a decade ago, and a handful of other hobbyists and independent nurserymen clung to the idea that many of these so-called extinct apple varieties might be living on, hidden from view in some obscure or overgrown orchard. Most of the apple trees planted in the past century, called old-timeor full-size, can live 75 years or longer, even under conditions of complete neglect. The apple sleuths questioned elderly gardeners, placed ads in periodicals and, in time, discovered that more than 300 Southern apple varieties were still flourishing. Today, with most pre-World War II orchards either gone or seriously in decline, time is running out to find other lost varieties.

When my grandfather, himself a retired nurseryman, learned of my interest in historical pomology, he handed me a manila envelope full of old fruit lithographs that had belonged to his father. "Dad sold fruit trees back in the '20s and '30s, he said. "These are from the plate book he used to carry."

When I spread the images out on my grandmother's pedestal kitchen table, it was as though my family tree were bringing forth fruit in its season. I marveled at the richly colored images of Maiden's Blush (waxen yellow with its cheek reddened toward the sun); Black Ben Davis (deep red, slightly conical, prized for its high-quality preserves); Johnson's Fine Winter (orangy red, queerly lopsided—yet deemed the "imperial of keepers"). I would learn as well that my grandfather's grandfather, C. C. Davis, started out in the nursery business back in 1876—and that virtually all of the more than 100 fruit varieties he propagated are now considered rare or extinct.

In the 19th century, fruit gardens were as common as vegetable or rose gardens are today. "Fine fruit is the flower of commodities," wrote Andrew Jackson Downing, author of the 1845 Fruits and Fruit Trees of America. "It is the most perfect union of the useful and the beautiful that the earth knows. Trees full of soft foliage; blossoms fresh with spring beauty; and, finally,—fruit, rich, bloom-dusted, melting, and luscious—such are the treasures of the orchard and garden, temptingly offered to every landholder in this bright and sunny, though temperate climate."

This boast could not have been made 200 years before.When the first colonists arrived at Jamestown, Virginia, in1607, there were no cultivated fruit trees in America—save for a few scattered Indian plantings—only wild crab apples, cherries, plums and persimmons. Taking a bite into a persimmon, Capt. John Smith commented, could "draw a man's mouth awry."

How much Smith influenced the subsequent introduction of new fruits to America is unknown. What is clear is that many colonists brought seeds, cuttings and small plants on the voyage over from Europe. Among the first to take root here was the May Duke cherry, the Calville Blanc d'Hiver apple, the Moor Park apricot and the Green Gageplum. Over the course of the next 300 years, the New World would experience a virtual revolution in the number and quality of apple and other fruit varieties.

"The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to its culture," Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1821. But it was less this noble sentiment than necessity, and thirst, that propelled America's early experimentswith fruit. "The apple was not brought to this country to eat, but to drink," says apple authority Tom Burford, whose family has been growing them since 1750. Jefferson's six-acre North Orchard was typical of family farms of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These so-called field or farm orchards averaged about 200 apple and peach trees each, bearing fruit for cider and brandy making, or for use as food for livestock. Farmers made applejack by placing fermented cider outside during the winter and removing the ice that formed, leaving a potent alcoholic liquid.

Unlike Europeans, most Americans did not have the luxury of propagating apple trees by cloning existing plants through budding or grafting. Grafting, which can be expensive and is labor intensive, is the only practical way to duplicate the exact characteristics of the parent tree. (It is done by joining a cutting, called a scion, to a rooted plant, called a rootstock. The scion grows and eventually bearsfruit.) The trees that colonists did bring over from Europe didn't do well in the harsher climate. As a result, most colonists planted apple seeds, which create haphazard results."Apples have . . . a dizzying mélange of inherited characteristics," writes Frank Browning, a journalist for National Public Radio who penned the book Apples in 1998."Any one 'mother' tree can produce a broad array of similar-looking apples whose seeds will produce 'daughter' apple trees that have completely different shapes . . . and create fruit with utterly different color, sweetness, hardiness,and shape." This rich genetic heritage makes the apple the hardiest and most diverse fruit on earth. But propagating apples is unpredictable.

A tree grown from an apple core thrown over the back fence usually bears fruit of only passable or inferior quality. But every once in a while, an apple with unusual and desirable characteristics arises. That is what happened time and again in cider orchards of the 17th and 18th centuries, orchards which served, in effect, as vast trial plots for the improvement of imported Old World stocks. Thus emerged,for instance, the small Hewes' Crab, possibly a cross between an apple of European stock and the crab apple, native to Virginia. In pressing the juice-filled Hewes' Crab for cider, wrote Philadelphia farmer Henry Wynkoop in 1814, "the liquor flows from the pumice as water from a sponge."

Many of these pippins, as the tree seedlings were called, thrived. By the mid-1780s, Jefferson could boast in a letter from Paris to the Rev. James Madison: "They have no apples to compare with our Newtown pippin." In fact, Virginia's Albemarle County, which includes Monticello, enjoyed a lucrative trade in exporting the Newtown Pippin to England.

One of the first American texts on pomology was written by William Coxe and published in 1817. A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees described "one hundred kinds of the most estimable apples cultivated in our country"—many of them true natives. And in 1869, Downing's revised edition of Fruits and Fruit Trees (edited by brother Charles, and even today considered the magnum opus of American pomology) described nearly 2,000 different apples, pears, peaches, plums and a host of lesser-known fruits—most of American origin.

That was the world in which John Chapman, better known as Johnny Appleseed, spread goodwill and goodseeds, trekking barefoot in a sackcloth shirt over Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana during the first half of the 19th century. The eccentric but resourceful Massachusetts native scouted routes along which pioneers would most likely settle. He bought land along these routes, on which he planted seedlings, which he would willingly dig up to sell to arriving settlers. By the 1830s, Chapman owned a string of nurseries that spread from western Pennsylvania, across Ohio and into Indiana. He died owning 1,200 acres of land in 1845. Chapman's story is about "how pioneers like him helped domesticate the frontier by seeding it with Old World plants," writes Michael Pollan in The Botany of Desire. "Without them the American wilderness might never have become a home." Chapman's frontier nurseries no doubt produced many valuable new apples. Perhaps a few of them even made it into W. H. Ragan's USDA, Bulletin No. 56, Nomenclature of the Apple, the essential reference for apple aficionados, which in 1905 cataloged more than 14,000 different apple varieties.

But the golden age of American pomology would come to an abrupt end in the early 20th century. Inexpensive railway shipping and refrigeration enabled orchards to transport apples year-round. Home orcharding declined as suburbs emerged. And when that quintessential mass-market apple, the patented, inoffensively sweet and long-lasting Red Delicious, took hold in the early 1920s, many high-flavored heirlooms were effectively cut out of the commercial trade. Today's mass merchandisers tend to view apple varieties in terms of color, disease resistance, shelf life and their ability to be shipped long distances without bruising. Grocery stores often stock only one red, one green and one yellow variety, which usually means a Red Delicious, a Granny Smith and a Golden Delicious. And as any consumer knows, those big, beautiful and perfect-looking apples can often taste like sweetened sawdust. Still, the apple remains big business in this country: about 7,500 commercial apple producers in 36 states harvest a total volume of 48,000 tons, second in production only to China. The average American consumes some 16 pounds of fresh apples a year, making the apple second only to the banana as the nation's most popular fruit.

Creighton Lee Calhoun, Jr., of Pittsboro, North Carolina, may be the most influential heirloom apple sleuth on the job today. A retired Army colonel with degrees in agronomy and bacteriology, Calhoun started collecting old apple varieties in the early 1980s. "Early on, it was sort of like a treasure hunt," he says. "I'd go knock on doors and ask: 'What kind of tree is that?' Most of the time the people would say, 'I have no idea,' or 'Granny knew, but she died in '74.' " It took Calhoun two years to locate his first antique apple—a Southern variety called Magnum Bonum. In 1983, he found an old North Carolina apple called Summer Orange, prized for making pies. Calhoun tracked another apple to a farm owned by E. Lloyd Curl in Alamance County, in North Carolina's piedmont region. "Curl said tome, 'Yeah, back during the Depression, I would sell apple trees for a local nursery. They paid me 10 cents for every tree I sold, and this was one of the varieties the nursery had; they called it the Bivins.'"

Calhoun took a cutting from the tree and grafted it onto one in his backyard orchard. (One of his backyard trees would eventually host 36 different varieties, each new scion grafted to a different limb.) In 1986, Calhoun came across a1906 catalog from an old North Carolina nursery, which indicated that the Bivins was actually a New Jersey apple called Bevan's Favorite. It originated before 1842 and sold in the South as a high-quality summer-eating apple. But like so many others, it was neglected and eventually disappeared; if not for Calhoun, it might have been lost altogether .Eventually, he would rediscover almost 100 lost varieties: apples such as Chimney, Prissy Gum, Dr. Bush's Sweet, Carter's Blue (retrieved from the National Fruit Trust in Kent, England), Clarkes' Pearmain (grown byThomas Jefferson) and the Notley P. No. 1.

"I came to the conclusion that the South was losing an irreplaceable part of its agricultural heritage," says Calhoun.So, beginning in 1988, with the help of his wife, Edith, he poured his research into a book, Old Southern Apples, a veritable bible of old apple information. Calhounis encouraged by the new interest that his book and the work of other antique apple sleuths have generated over the past several years.

"In the past five years," he says, "people have been breaking out of the Red Delicious strait jacket and becoming more adventurous, seeking out and buying apples of different colors and flavors." In Washington State, for instance, Red Delicious production has fallen 25 percent over the past five years as commercial growers plant less well-known varieties, such as Braeburn, Jonagold, Gala, Cameo and Pink Lady.

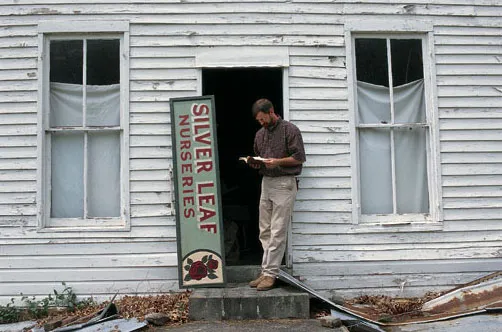

While reading Calhoun's long list of extinct varieties, I came across a reference to an apple called the Reasor Green, which I knew from one of my family lithographs: a large green apple mottled with surface discolorations known as flyspeck and sooty blotch. (Nineteenth-century illustrators unabashedly recorded both beauty and blemish.) But what really caught my eye was the source for Calhoun's description: the 1887 Silver Leaf Nurseries catalog by my great-great-grandfather C. C. Davis. I had never seen a copy of the catalog, so I eventually got myself over to the National Agricultural Library in Beltsville, Maryland, to check it out. Wearing the required white gloves, I openedit gingerly and began reading my great-great-grandfather's "Prefatory" remarks. "We have greatly extended our operations, the past few years," he wrote, "having confidence that the planting spirit already manifest will continue to increase till every table be fully supplied with wholesome refreshing fruits."

Alas, his optimism would prove misplaced. Of the 125 apple, pear, cherry, peach and plum varieties he describes, only a handful—the Winesap and Rome Beauty apples, and the Bartlett and Kieffer pears—are still grown widely today. Yet of the 60 apple varieties he lists, I now grow half of them in my nursery.

It is for me a very direct connection to the past. But some antique apple varieties live on in a more indirect form. Another old apple by the name of Ralls Genet, for example, was a favorite of Jefferson's. As the story goes, the third president obtained cuttings of it from his friend, Edmund Charles Genet, French minister to the United States, and gave some to local nurseryman Caleb Ralls. The subsequent Ralls Genet variety soon became a popular apple in the OhioValley because of its late bloom—which allows it to weather late-season frosts. It was crossed by Japanese breeders with the Red Delicious, and the resulting apple, released in 1962, went on to become the now commercially popular Fuji, which recently overtook the Granny Smith as the third most popular apple in the United States (behind the Red Delicious and the Golden Delicious). As Peter Hatch, director of gardens and grounds at Jefferson's Monticello, noted at a recent apple tasting, "We like to say that Thomas Jefferson was not only the author of the Declaration of Independence and the father of the University ofVirginia but perhaps the grandfather of the Fuji."

My own great-great-grandfather would no doubt be proud to know that I am growing the "Rawle's Janet" today—a variety that he, like many others of his time, misspelled. I suspect, however, that he would be even more pleased to know that I was able to propagate the Reasor Green in the spring of 2001. For it was my great-greatgrandfather, in 1886, who introduced that very apple to the trade after he found it in a neighbor's orchard. He grafted itonto existing trees and began selling cuttings, called whips.

Had I not read Lee Calhoun's book, I probably wouldn't have given the Reasor Green much thought. But when I saw the word "extinct" next to what amounted to a family heirloom, I was motivated to get out of the nursery and see what I could turn up. For me, that meant talking with family and any friends who might know where an old Reasor Green tree was still standing. And it didn't take long to get a hot lead. When I told my story to Harold Jerrell, an extension agent in Lee County, Virginia, where the Silve rLeaf Nurseries had been located, he said, "Yeah, I knowthat one's not extinct." He recommended that I contact Hop Slemp of Dryden, Virginia. So I called Slemp, a beef and tobacco farmer, who said that he did have a Reasor Green and invited me to stop by for a visit the third weekof October when the apples would be ready to pick. Would the Reasor Green—the regional pronunciation is Razor Green—turn out to be a "spitter," an apple so bitter that it provokes a universal response? Spitters, according toTom Burford, make up a disappointing 90 percent of all heirloom apples.

On the appointed October day, my four sons and I headed off in the family car, driving deep into the valleyridge province of southwest Virginia. By the time we pulled into Slemp's gravel driveway, the sun was already low in the hazy, autumn sky. Buckets of apples were spread haphazardly in his carport.

After a few minutes, the 65-year-old Slemp pulled up in his Ford pickup. We piled into it, headed east for a quartermile and turned onto a paved road that winds past scattered groves of tulip poplars and Virginia cedars. Finally, we pulled into a farm lane that had several apple trees planted beside it. Stopping at a heavy metal gate, we climbed out and inspected what Slemp calls an "old-timey Winesap," loaded with dull red apples. I picked one off the tree and took a bite, luxuriating in the snappy, vinous flavor. Then we gathered a couple dozen more to eat later.

We got back in the truck and followed the lane a little farther up the ridge. "This here's the Reasor Green," Slemp said, pointing to a well-branched specimen with leaves as leathery as his hands. "It's been so dry, most of the apple shave already dropped. Usually, this time of year, it's loaded." Sure enough, on the ground lay bushels of large green apples, mottled as promised with flyspeck and sootyblotch—clearly the very apple my great-great-grandfather propagated a century and a quarter ago.

What does a Reasor Green taste like? Well, I'd love to slap you on the back and let you try one of these juicy apples for yourself. But short of your visiting southwest Virginia, that's probably not going to happen. I can tell you, though, that after visiting with Slemp, we brought a whole bucketful of Reasor Greens home. And for my 39th birthday, my wife made two Reasor Green apple pies. It's not enough to tell you they tasted like manna from heaven. I give the final word, instead, to my great-great-grandfather. The Reasor Green, he wrote 115 years ago, is one of those fruits "so beneficently offered by the Creator to every husband man."