This Ancient Creature Shows How the Turtle Got Its Shell

The 240-million-year-old “grandfather turtle” may be part of the evolutionary bridge between lizards and shelled reptiles

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/0e/600ec612-3dca-4fa8-b74c-133802b37aef/turtle_.jpg)

Turtles are pretty mellow creatures, but they excel at causing strife among paleontologists. Researchers have long been left guessing as to how soft-backed animals somehow transitioned into the shell-carrying creatures we know so well today. Now, they have finally found fossils that help fill in the details of this critical evolutionary period.

The fossils, discovered in an ancient lakebed in Germany, belong to a newly named species called Pappochelys, Greek for “grandfather turtle.” Estimated to be about 240 million years old—putting it smack dab in the middle of the Triassic period—Pappochelys seems to hit the evolutionary sweet spot between older suspected turtle ancestors and more recent and established family members.

Rainer R. Schoch from the Natural History Museum in Stuttgart, Germany, and Hans-Dieter Sues at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., gleaned knowledge about Pappochelys by studying an assortment of 18 fossil specimens, plus one skull. As they report today in Nature, the living animal would have been about 8 inches long from nose to tail, roughly the same size as a modern-day box turtle.

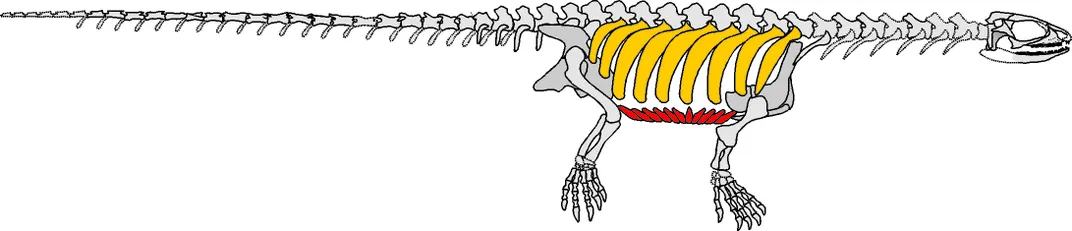

Pappochelys looked quite different than the turtles and tortoises of today, however. The animal had no shell, but it did have what appear to be the makings of one. Its ribs are broad and sturdy, and they fan out from the spine, a physiological set-up that the researchers suspect evolved not only for protection but also as a “bone ballast”—a way for the animal, which was likely aquatic or semiaquatic, to better control its buoyancy. That wasn’t the only hint of what would eventually become turtles’ trademark feature: Pappochelys also has a line of hard, almost shell-like bones along its belly.

Pappochelys is critical for understanding “a new stage in the evolution of the turtle body plan,” the researchers write. Prior to this discovery, a 220-million-year-old specimen from China, which displayed a partly formed shell and other turtle-like features, was the closest thing experts had to a seemingly sure-fire turtle relative. Other specimens, including a 260-million-year-old fossil from South Africa, were hypothesized to represent an even earlier turtle ancestor, but with such a large temporal gap separating them from the China specimen, researchers could not say for sure. Morphologically and chronologically, Pappochelys fits neatly between the two specimens, tying them together.

"At the time during which turtles evolved, all continents formed a single giant landmass known as Pangaea," Sues says in an email. "Thus, there were few—if any—major obstacles to the dispersal of animals, so [fossils of] very closely related species can be found in South Africa and China, among other places."

In addition to illustrating how the turtle's shell evolution likely took place, Pappochelys helps answer another hotly debated question: whether turtles are more closely related to lizards and snakes or to dinosaurs and birds. Based on an examination of Pappochelys’ skull, the researchers now possess evidence that turtles and tortoises fall firmly within the lizard and snake camp.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Rachel-Nuwer-240.jpg)