A Mine of Its Own

Where miners used to dig, an endangered bat now flourishes, highlighting a new use for abandoned mineral sites

One December afternoon, we walk straight into the hill, trading the winter woodland’s gray light for a shadow world of stone. The air grows still and moist. The tunnel divides, turns, then divides again. Suddenly, the darkness is so dense I feel I have to push it aside, only to have it close in behind me. Most of the passageways are roomy enough—about 20 feet high and 30 feet wide—to keep claustrophobia at bay.

We are inside the Magazine Mine, part of a 2,100-acre property near Tamms, Illinois, owned by UNIMIN Specialty Minerals Inc. The company worked the mine from 1972 to 1980, digging 20 acres of tunnels reaching as deep as 300 feet to extract microcrystalline silica, a fine quartz sand used in products like lens polish, paint and pool cue chalk.

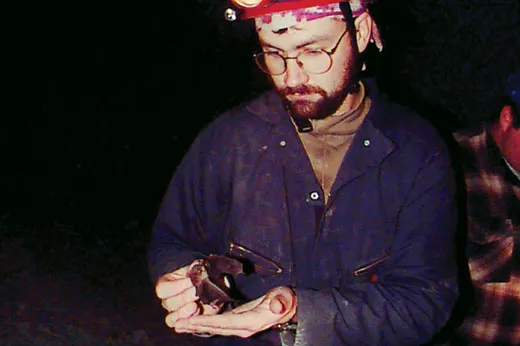

The first bats we see are tiny, grayish, thickly furred Eastern pipistrelles. They’re hibernating, hanging upside down with their wings folded. Beads of condensation coat their fur. In the light of our headlamps, they look like strange, glistening underworld fruits. Farther along are Northern long-eared bats, big brown bats and little brown bats. At last we come to Indiana bats, Myotis sodalis, no larger than mice, huddled in groups of one or two dozen. The animal’s pink nose distinguishes it from other small, brownish bats.

Then, on the upper curve of a light-colored wall is what appears to be a tacked-up beaver pelt. But in actuality, it’s more Indiana bats—about 2,000 of them, says Joe Kath, a biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and the leader of our subterranean expedition. “From photographs, we’ve counted 300 animals per square foot in clusters like this,” he says, “and sometimes as many as 500.” Each furry throng we encounter bodes well for the Indiana bat, which has been classified as endangered since 1967, and also for the Bats and Mines Project, an unusual collaboration between conservationists and industry officials.

Out of the roughly 5,416 known species of warmblooded, milk-producing vertebrates, at least 1,100 are in the order Chiroptera, Latin for “hand-wing.” In other words, about one out of every five kinds of mammal belongs to the much-reviled and still poorly understood group we call bats. North America is home to 46 bat species; most are insectivorous, with some consuming more than their weight in bugs in a matter of hours, and most have undergone substantial population declines. In addition to the Indiana bat, five North American species are officially endangered: the lesser long-nosed bat, the Mexican long-nosed bat, the gray bat, the Ozark big-eared bat and the Virginia big-eared bat.

Indiana bats, once so abundant in the East and Midwest that a single cave might hold millions, slipped below one million total population in the 1960s and at last count, in 1999, numbered only around 350,000, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Some experts predict that if current population trends continue, the species might be extinct as soon as 2030. The primary known cause of the decline is one that most bat species in the United States are facing: loss of hibernacula, or sites in which they can hibernate undisturbed.

A hibernating bat, with its heartbeat and breathing and body temperature all decreased, is exceedingly vulnerable, and people have destroyed entire wintering colonies, sometimes deliberately, sometimes inadvertently. Just rousting a bat out of hibernation may eventually kill it; its small body has just enough fat in reserve to get through the winter, and awakening the animal consumes precious fuel. Large caves have been emptied of bats by vandals, explorers, spelunkers and tourists. With undisturbed caverns becoming scarce, North American bats have increasingly turned to abandoned mines as a last resort.

As it happens, the Magazine Mine is well suited to the Indiana bat, which Kath says has the narrowest temperature tolerance during hibernation of any Midwestern bat—about 39 to 46 degrees. If the temperature gets much warmer, he says, the bat’s metabolism speeds up and it may burn through its stored fat and starve; if colder, it succumbs to the chill or wastes energy searching for a warmer spot.

Though one might think that coaxing bats to live in an old mine is no great feat, the effort has required close cooperation among parties that don’t always get along. Generally, mining companies preferred to seal off spent mines for public safety. Then, a decade ago, Bat Conservation International, Inc., based in Austin, Texas, and the federal Bureau of Land Management started the Bats and Mines Project, to make some nonworking mines accessible to flying—but not bipedal—mammals.

UNIMIN first approached the bat conservation group for advice in 1995. Workers welded a steel grid over the mine’s air-intake shaft, allowing bats to come and go. With state and federal money, volunteers erected a fence around the main entrance and installed 49 metal arches to stabilize the tunnel. The project, completed in 2001, cost nearly $130,000.

The mine’s Indiana bat colony has grown dramatically. In 1996, there were just about 100 bats, according to the initial census; by 1999, the population had increased to 9,000; by 2001, to 15,000; and by 2003, to more than 26,000. In fact, their numbers have been rising faster than the species can breed, meaning the mine must be attracting bats from other areas. “One day, this single site might hold more Indiana bats than anywhere else,” says Merlin Tuttle, president of Bat Conservation International. While the species is still declining in North America overall, populations are also flourishing in protected mines in New York, New Jersey, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The Magazine Mine is one of more than 1,000 former U.S. mines that have been turned into bat sanctuaries since 1994, safeguarding millions of bats of at least 30 different species, Tuttle says. Near Iron Mountain, Michigan, the Millie Hill Mine, formerly worked by an iron-mining company, holds hundreds of thousands of little and big brown bats. And across the West, some 200 gated mine sites have helped keep the Western big-eared bat off the endangered list.

Meanwhile, bats seem to have gained a little respect. “In ten years,” Kath says, “it’s gone from people bashing bats in the attic to people asking me for advice on how to build boxes in their backyard” to house the animals, among nature’s most efficient bug zappers.

In the Magazine Mine, it occurs to me that the project has exposed a myth as misguided as the notion that all bats are blind—that every endangered species will generate an ugly battle between conservationists and industry. Here, living, squeaking evidence that cooperation is possible covers the ceiling. What better agent to upend conventional wisdom than a flying mammal that sleeps upside down?