There’s a New Breed of Forty-Niners Rushing to the Pacific

Lured by the soaring price of the precious metal, prospectors are heading for the California hills like it’s 1849 all over again

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/America-Gold-Rush-nugget-631.jpg)

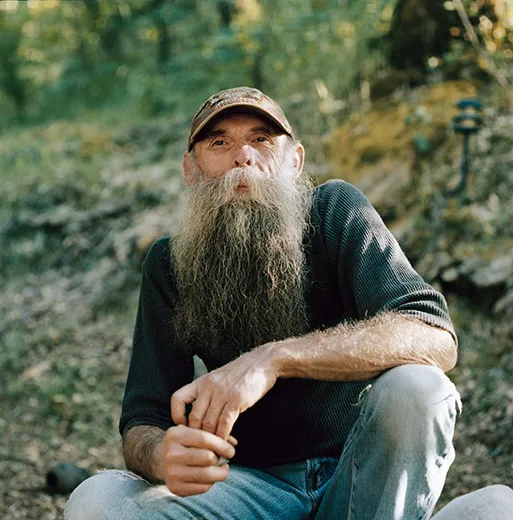

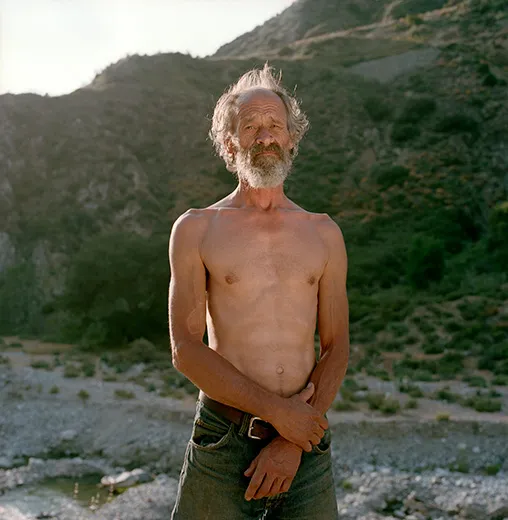

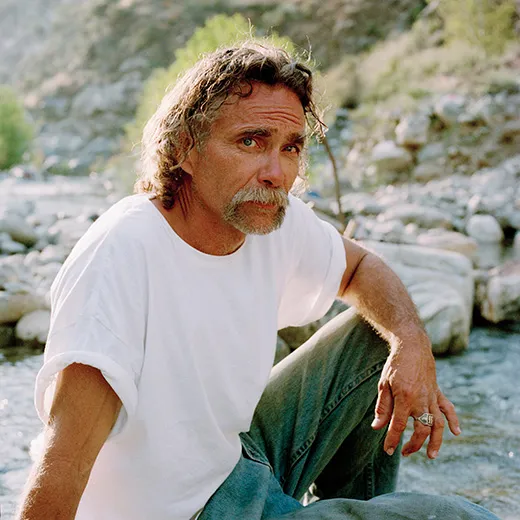

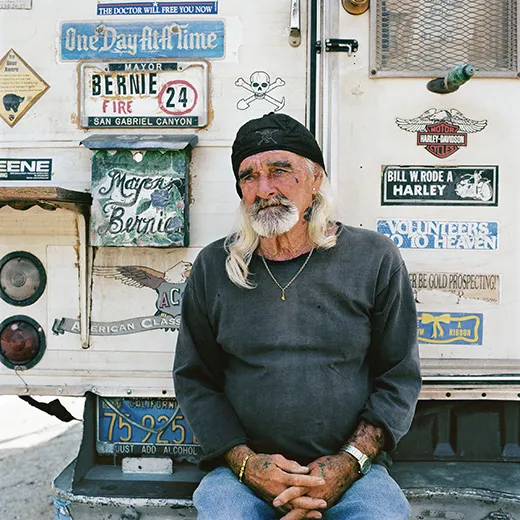

Nugget Alley is a fabled fork in the San Gabriel River just an hour outside Los Angeles. Gold prospectors with names like Backpack Dave, Recon John and the Bulldozer are again flocking there, and to California’s other strike-it-rich waterways. In previous lives they were movie lighting techs and Caribbean sport boat captains and penny-stock investors and soldiers. Now all day they hunt for color against gray river rocks.

Their ramshackle camps have, by some estimates, doubled over the past four years as the unemployment rate spiked and the precious metal skyrocketed to a record high of more than $1,500 an ounce. Scores of hard-core prospectors work the San Gabriel, and perhaps 50,000 people throughout the state prowl a few weekends a year with pans and metal detectors and dowsing rods. If they’re lucky, they find yellow powder as fine as flour, “clinkers” (big nuggets named for the pleasing sound they make on the bottom of a pan) or sculptural crystalline specimens that, stared at long enough, resemble lace doilies and dragons.

Occasionally, a five-ounce nugget comes to light, and a highly skilled and tenacious prospector might pull $1,000 out of the ground on a day fortune is with him. But most find just flecks, barely enough to keep them in groceries, for all their exertions. River miners crush fingers, toes and even teeth shoving aside huge boulders to reach the gleam beneath. “I’ve been buried under the water three times,” says Bernie McGrath, a prospector and former pipeline worker. “It’s a treacherous way to make money.” It’s also, in Nugget Alley (part of the Angeles National Forest), unauthorized.

Sarina Finkelstein, a photographer at work on a book about California’s “New 49ers,” as she calls them, wonders if something besides the dream of wealth has been driving them. “You can photograph the gold,” says Finkelstein, who previously documented street performers in New York City’s Central Park. “You can photograph the landscape. You can photograph the faces. But how do you photograph a motivation?”

California’s identity is veined with gold. The modern jackpot industries (Hollywood and high-tech) inherited their air of perpetual optimism from the myriad boys and men who, upon hearing of the gold discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January of 1848, waited for the spring prairie grass to grow, then steered their wagons for the bonanza.

“The gold was available to anybody with a pick and a pan,” says Malcolm J. Rohrbough, a historian and author of Days of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. “There was no license you had to buy. There was no central authority. This was one of the most remarkable examples of the democratization of the economy. It was open to all Americans, as our national myth says it should be.”

California wasn’t yet a state, but, thanks to the forty-niners, soon it would be. Within a few years, there were 100,000 prospectors, many of them factory workers and farmers accustomed to measuring profits in pennies. Some grew rich—a good miner could make $20 a day, compared with the national average of $1—and others made their fortunes supplying miners. Leland Stanford, founder of the university bearing his name, got his start provisioning prospectors. So did Levi Strauss.

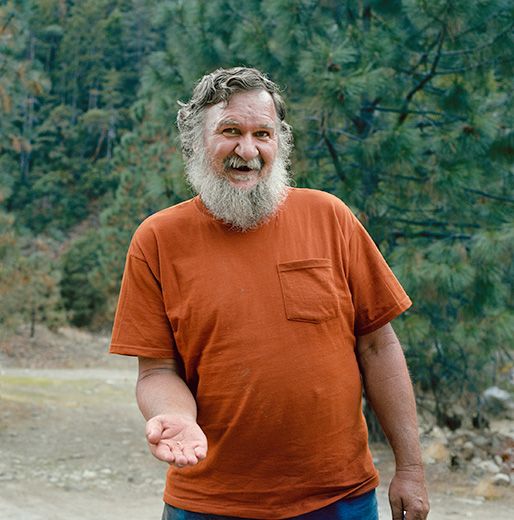

The lifestyles of the modern-day prospectors are, in some respects, not so far removed from that of the forty-niners, judging from Finkelstein’s portraits. With their streaming beards, profound sunburns and fingernails caked with river mud, they could have wandered out of the mid-19th century, even though many have outfitted themselves via get-rich-on-gold websites—apparent successors to Stanford and Strauss. There is no cellphone reception at the mining camps and few modern amenities, and the tools of the trade have barely changed: many prospectors use the pan and sluice. They scour the same rivers, often looking for gold the forty-niners missed. In fact, in 2009 California banned a popular dredging technique in part because the miners were stirring up mercury deposits that the forty-niners (who used the toxic metal to attract fine-grained gold) had left behind. California environmentalists, who also fought the first gold rush, continue to raise concerns about how gold miners affect the landscape.

The atmosphere in the camps may well be darker than in the old days. A number of miners “are desperate people and they don’t know anything about gold mining, but they have a dream that you can make a living doing this, and it’s sad,” says Gregg Wilkerson, a Bureau of Land Management gold mining expert.

“The forty-niners wanted to be a part of building a society and a community, but most of the prospectors I’ve met these days, they just want to be left alone,” says Jon Christensen, executive director of Stanford’s Bill Lane Center for the American West.

Perhaps the starkest difference between the modern prospectors and their predecessors is age. The gold rush was a young man’s game, but many of today’s miners are cash-strapped retirees trying to add a little shine to their golden years. This gives the new mining movement, Christensen says, “the feeling of being the end of something, rather than the beginning.”

Still, Finkelstein believes the latter-day miners share something of the forty-niners’ spirit. “They don’t have to be gold prospecting,” she says, adding: “There’s a certain personality to gold prospectors. In many ways it’s the personality you get from an excited 7-year-old boy who wants to go out exploring every day, to take a risk, to gamble, to get his hands dirty.”

Most on Nugget Alley are free of car and house payments. They enjoy the shade of the riverside alders and hook the occasional trout. And every night they have front-row seats to the glorious San Gabriel sunset, which gilds the river and turns the dusty mountains gold.