The Fatal Consequences of Counterfeit Drugs

In Southeast Asia, forensic investigators using cutting-edge tools are helping stanch the deadly trade in fake anti-malaria drugs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Cambodia-rural-poor-malaria-631.jpg)

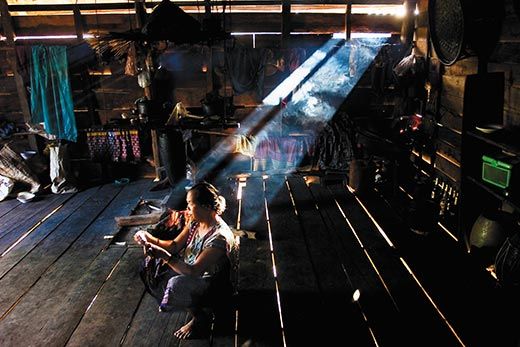

In Battambang, Cambodia, a western province full of poor farmers barely managing to grow enough rice to live on, the top government official charged with fighting malaria is Ouk Vichea. His job—contending with as many as 10,000 malaria cases a year in an area twice as large as Delaware—is made even more challenging by ruthless, increasingly sophisticated criminals, whose handiwork Ouk Vichea was about to demonstrate.

Standing in his cluttered lab only a few paces wide in the provincial capital, also called Battambang, he held up a small plastic bag containing two identical blister packs labeled artesunate, a powerful antimalarial. One was authentic. The other? "It's 100 percent flour," he said. "Before, I could tell with my eyes if they were good or bad. Now, it's impossible."

The problem that Ouk Vichea was illustrating is itself a scourge threatening hundreds of thousands of people, a plague that seems all the more cruel because it is brought on by cold, calculated greed. Southeast Asia is awash in counterfeit medications, none more insidious than those for malaria, a deadly infectious disease that is usually curable if treated early with appropriate drugs. Pharmacies throughout the region are stocked with the fake malaria medicine, which is generally cheaper than the real thing.

Artesunate, developed by Chinese scientists in the 1970s, is a leading antimalaria drug. Its active ingredient, artemisinin, comes from the wormwood plant, which ancient Chinese herbalists prized for its fever-reducing properties. Between 1999 and 2003, medical researchers conducted two surveys in which they randomly purchased artesunate from pharmacies in Cambodia, Myanmar (formerly Burma), Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. The volume of fake pills rose from 38 percent to 53 percent.

"This is a very, very serious criminal act," Nicholas White, a malaria expert at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand, says of the counterfeiting. "You're killing people. It's premeditated, coldblooded murder. And yet we don't think of it like that."

Nobody knows the full scope of the crime, although the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that counterfeit drugs are associated with up to 20 percent of the one million malaria deaths worldwide each year. Reliable statistics in Southeast Asia are hard to come by, partly because the damage seldom arouses suspicion and because victims tend to be poor people who receive inadequate medical treatment to begin with.

That dimension of the problem was made clear to me by Chem Srey Mao, a 30-year-old farm laborer in Pailin, Cambodia. She said she had been sick with malaria for two weeks before she finally visited the district's main health clinic, a one-story building with a handful of rooms. She had been dosing herself with painkillers so she could work in the fields, sometimes collapsing in the afternoon with fevers and chills. "I needed the money for medicine and food," she said. "I had to work."

The most afflicted populations live in remote, rural areas and have limited access to health facilities. An estimated 70 percent of malaria patients in Cambodia seek treatment at local village vendors, who don't have the expertise or resources to distinguish real pills from counterfeits.

"The first time they get sick they go to a private clinic or small pharmacy," Ouk Vichea says. "Only when it's severe do they go to the hospital." And then it's often too late.

Compared with what Americans typically pay for drugs, genuine artesunate is cheap in Southeast Asian countries—around $2 for the standard treatment of a dozen pills. But that's still 20 times more expensive than an earlier antimalarial, chloroquine, now seldom used because the malaria parasite has evolved resistance to it. And in Cambodia, where the average per capita income is just $300 a year, the nickels or dimes people save buying counterfeit artesunate pills represent significant savings. "It's the number one fake," says Ouk Vichea.

Bogus medicines are by no means limited to malaria or Southeast Asia; business is booming in India, Africa and Latin America. The New York City-based Center for Medicine in the Public Interest estimates that the global trade in fake pharmaceuticals—including treatments for malaria, tuberculosis and AIDS—will reach $75 billion a year in 2010. In developing countries, corruption among government officials and police officers, along with weak border controls, allow counterfeiters to ply their trade with relative impunity. Counterfeiting is "a relatively high-profit and risk-free venture," says Paul Newton, a British physician at Mahosot Hospital in Vientiane, Laos. "Very few people are sent to jail for dealing in fake anti-infectives."

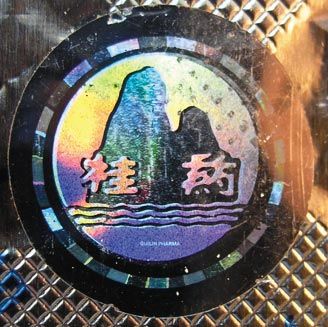

When the fake artesunate pills first appeared in Southeast Asia in the late 1990s, they were relatively easy to distinguish. They had odd shapes and their packaging was crudely printed. Even so, Guilin Pharmaceutical, a company based in southern China's Guangxi autonomous region and one of the largest producers of genuine artesunate in Asia, took extra steps to authenticate its medication by adding batch numbers and holograms to the packaging. But the counterfeiters quickly caught on—new and improved fakes appeared with imitation holograms.

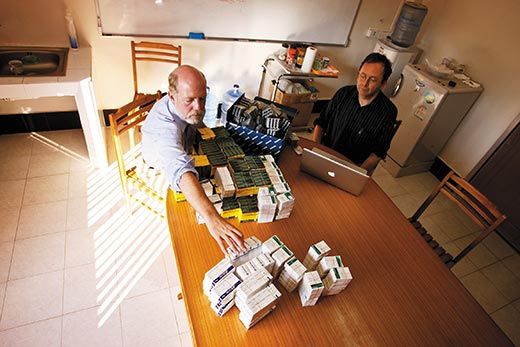

Then, in May of 2005, with the counterfeiters gaining ground, a number of physicians, officials, researchers and others gathered at the WHO regional office in Manila. Public health experts agreed to join forces with the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol). They would try to track down the sources of the bogus artesunate and disrupt the trade. They would launch an investigation like no other, drawing on an extraordinary range of authorities in subjects from holography to pollen grains. They would call it the Jupiter Operation.

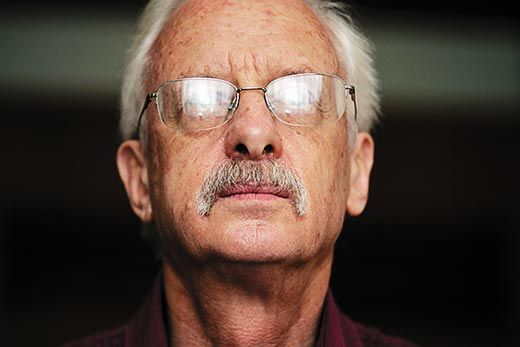

Paul Newton attended that first meeting in Manila, which he recalls was held in an atmosphere of "some desperation." He would coordinate the scientific investigation, which included experts from nine countries. "No one had tried to bring diverse police forces, forensic scientists, doctors and administrators together before," he says.

The goal was to gather enough evidence to halt the illicit trade by putting the counterfeiters behind bars. But first they had to be found. The investigators collected 391 "artesunate" samples from across Southeast Asia and subjected each pill packet to a battery of tests. "We were all working on pieces of a puzzle," says Michael Green, a research chemist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. "When these pieces—chemical, mineralogical, biological, packaging analysis—were compared and assembled, a picture of where many of these counterfeits were coming from began to emerge."

The investigators pored over each package. In some cases, a mere glance was sufficient to spot the fakes: lettering was misaligned or words were misspelled ("tabtle" instead of "tablet"). Most of the time, though, the flaws were more subtle.

To examine the holograms, Newton called in a British holography expert named David Pizzanelli. The son of a Florentine painter, Pizzanelli had studied holography at London's Royal College of Art, and his artwork has been exhibited at top British galleries. He has lent his expertise to the Counterfeiting Intelligence Bureau, part of the anti-crime unit of the Paris-based International Chamber of Commerce.

The Jupiter Operation "was extreme in several ways," Pizzanelli says. "It was the first time I'd seen such an abundance of counterfeits, probably with the exception of Microsoft." (Bogus versions of Microsoft software blanket the world, costing the company billions of dollars.) Pizzanelli identified 14 types of fake Guilin Pharmaceutical holograms. "It's a unique case in terms of how many counterfeit holograms there are. The real one just gets lost in the avalanche of images."

The hologram that Guilin itself puts on its artesunate packages—two mountains above a coastline with rolling waves—was fairly rudimentary to begin with. Some counterfeit copies were "deeply awful," he recalls. "The first two weren't even holographic," including an illustration etched into rainbow-colored foil. Some of the bogus holograms were well crafted but had clear errors: the waves were too flat or the mountains sprouted extra plateaus.

But a couple of the fake holograms exhibited flaws that defied easy detection: the colors were just slightly brighter than the genuine article, or the 3-D image had slightly more depth than Guilin's hologram. One hologram Pizzanelli studied was actually more sophisticated than the real article. Buyers would be "guided towards the fake," he says, "because the fake was better made than the genuine." That troubled Pizzanelli, who says he'd never before done holography detection with a "life-or-death implication."

Green, of the CDC, had previously developed an inexpensive field test for detecting fake artesunate pills. In Atlanta, for the Jupiter Operation, his lab separated, identified and measured the contents of the pills. The fakes contained an astonishing variety of drugs and chemicals, some of them downright toxic. There was metamizole, a drug that can cause bone marrow failure and is banned in the United States; the outmoded drug chloroquine, which might have been added to create the bitter taste that many Asians associate with effective antimalarials; and acetaminophen, a pain reliever that can dull such malaria symptoms as pounding headaches and fool patients into thinking they're getting better. Jupiter Operation analysts also found safrole, a carcinogenic precursor to MDMA—better known as the illicit narcotic Ecstasy. The traces of safrole suggested that the same criminals who produced party drugs were now producing fake antimalarials.

Making matters worse, some of the bogus pills contained small amounts of genuine artesunate—possibly an effort to foil authenticity tests—which could cause the malaria parasite, spread by mosquitoes, to develop resistance to the leading drug treatment for the disease in Southeast Asia. That would be a public health disaster, researchers say. "We were shocked to find out how serious the problem was," says Newton.

The chemists also found that the fake drugs could be identified by their excipient—the inactive substance that carries the active ingredient in a tablet. The main excipient in Guilin artesunate is cornstarch. But geochemists on the team identified the excipient in some counterfeits as a particular type of calcium carbonate mineral, called calcite, which is found in limestone. That discovery would later take on greater significance.

The Jupiter Operation was the first time that palynology—the study of spores and pollen grains—was employed to trace counterfeit drugs. Plant species produce millions of pollen grains or spores, which end up almost everywhere. If a pollen grain's dispersal patterns (what palynologists call "pollen rain") are known, along with the locations and flowering times of the plants, then pollen can indicate where and when an object originated. Trapped in air filters, pollen can even reveal the routes of planes, trucks and cars.

Dallas Mildenhall is an expert (some would say the expert) in forensic palynology. Working from his lab at GNS Science, a government-owned research institute, in Avalon, New Zealand, he is a veteran of more than 250 criminal cases, involving everything from theft to murder. In 2005, Paul Newton asked him if he could extract pollen samples from antimalarials. "I was fairly certain I could," Mildenhall says. He views the trade in fake antimalarials as his biggest case yet. "It is mass murder on a horrendous scale," he says. "And there appears to be very little—if any—government involvement in trying to stamp it out."

In the fake drugs, Mildenhall found pollen or spores from firs, pines, cypresses, sycamores, alders, wormwood, willows, elms, wattles and ferns—all of which grow along China's southern border. (The fakes also contained fragments of charcoal, presumably from vehicle tailpipes and fires, suggesting the phony drugs were manufactured in severely polluted areas.) Then Mildenhall discovered a pollen grain from the Restionaceae family of reeds, which is found from along the Vietnam coast into southernmost China. That location matched the source of the calcite identified by Jupiter Operation's geochemists.

"A mine close to the China-Vietnam border is the only place in the world where this type of calcite is mined," Mildenhall says. The investigators now had two pieces of evidence for the general location of the counterfeit-drug-manufacturing facilities.

Based on their analyses, Jupiter Operation researchers determined that 195 of the 391 random samples were counterfeits. The pollen signatures from nearly all of them suggested that they'd been manufactured in the same region of southern China. The researchers then created a map, pinpointing where each of the 14 fake holograms had been found. The locations suggested the counterfeits were made and distributed by two separate trafficking networks. One encompassed a western region (Myanmar, the Thai-Myanmar border and northern Laos); the other an eastern area (southern Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia). What's more, metronidazole (an antibiotic) and small amounts of artesunate were detected exclusively in the western samples, while erythromycin (another antibiotic), erucamide (an industrial lubricant), sulphadoxine and pyrimethamine (older antimalarials) were found only in the eastern counterfeits.

At this stage of the investigation, the Jupiter Operation had done all that it could to locate the counterfeiters' production facilities. "We were able to pinpoint only a general area," says Mildenhall. "We were now totally dependent on the local law enforcement agencies to target that area and find out the precise spot."

With evidence from the Jupiter Operation in hand, Ronald Noble, the secretary general of Interpol, met in March 2006 with Zheng Shaodong, China's assistant minister of public security. During the meeting, Noble stressed to Zheng not only the threat to public health, but the potential profit losses for Chinese pharmaceutical companies.

China's Ministry of Public Security launched its own investigation (it had also arranged for Mildenhall to analyze the samples' pollen). Finally, the authorities arrested three individuals—two buyers and a seller —in southern China for their roles in trafficking 240,000 blister packs of fake artesunate into Myanmar. They were all convicted: two of them were sentenced to one year and nine months imprisonment and one was sentenced to five months imprisonment.

But the manufacturers of the counterfeit artesunate were never found. And only one-tenth of the 240,000 blister packs were seized. The rest disappeared inside Myanmar, where nearly half of all malaria-related deaths in Asia occur, according to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

With only three convictions, was it all worth it? Yes, says Mildenhall, who notes that the number of counterfeit antimalarial tablets entering Southeast Asia dropped the following year. "Just saving a few lives would have made it worthwhile," he adds.

Newton says he was "absolutely delighted" with the Chinese government's response. "We're not suggesting that's the end of the problem," he adds. "Police action will suppress [the trade] but won't eliminate it." And while the Jupiter Operation has emerged as an effective model for investigations into counterfeit drugs, such efforts require political focus as well as money, equipment and unique scientific expertise—all of which tend to be in short supply in developing countries.

In the meantime, Newton says a number of steps could stanch the distribution of counterfeit medicines: cheap, high-quality antimalarials must be made widely accessible; medical authorities in poor countries must be given the financial and human resources to inspect supplies; and health workers, pharmacists and the public must be made aware that drug quality is a matter of life and death.

Assistance from pharmaceutical companies will also be crucial. "They're often the first people to identify fakes, but there's a disincentive for them to declare that because it destroys their market," says White. "So they hush it up."

In 2005, White and Newton wrote to 21 major drug manufacturers, asking what their policy would be if they learned that any of their products were being counterfeited. Only three companies replied that they would contact drug regulatory authorities.

Newton praised Guilin Pharmaceutical for taking part in the Jupiter Operation. Still, confidence in Guilin-made artesunate appears to have been shattered. I spoke to the owners of a dozen mom-and-pop drugstores in Pailin, Cambodia, and none stocked Guilin's artesunate. "I don't dare sell it," says Ruen Mach, whose small shack in Cheav village brims with sun-faded packets of medicine.

Local residents once claimed they could tell the real thing by the quality of the packaging, or by the steepness of the mountain peak that makes up the Guilin logo. Not any more.

In another malaria-stricken area of Cambodia, I showed a medic named Rous Saut a photo of the two blister packs that Ouk Vichea had shown me.

"This is probably fake," Rous Saut said. He was pointing to the genuine one.

Bangkok-based freelance journalist Andrew Marshall writes about Asian affairs and is profiled in "From the Editor". Photographer Jack Picone is based in Bangkok.