In Seattle, a Northwest Passage

He arrived unsure of what to expect—but the prolific author quickly embraced Seattle’s energizing diversity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/northwestpassage_sept08_631.jpg)

I was hired in 1976 to teach at the University of Washington, and so made the cross-country drive to Seattle from Long Island, where I'd been a doctoral student in philosophy at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. But before leaving for a part of the country completely unknown to me (I'd never been west of the Mississippi), I mentioned to my friend and mentor, the novelist John Gardner, that my wife, newborn son and I were moving to the Pacific Northwest. I remember he paused, pushed his vanilla-colored Prince Valiant hair back from his eyes and looked as if a pleasant image had flickered suddenly through his mind. Then he said, "If my daughter ever married a black man, the first thing I'd do is ask her to move to Seattle."

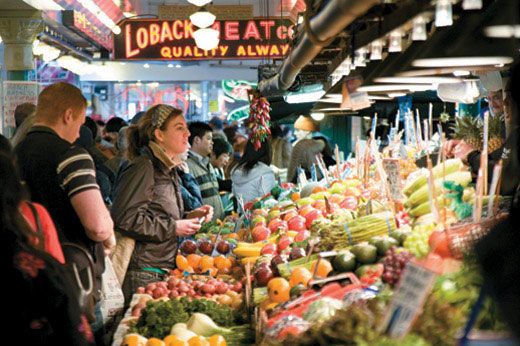

Now I knew how fiercely Gardner loved his children, but at the time I was unable to unlock his meaning. The first day I set foot in this city, however, I began to glimpse what he meant. It was peopled with every sort of American I could imagine: Native Americans, whites who sprang from old Scandinavian and German stock, Chinese and Japanese, Senegalese and Eritrean, Hindu and Sikh and Jewish, gay and lesbian, and blacks whose families settled in the territory in the late 19th century. It was a liberal city remarkably similar in texture and temperament to San Francisco (both are built on seven hills, have steep streets and have burned to the ground).

Former UW president William Gerberding once referred to the Northwest as "this little civilized corner of the world," and I think he was right. The "spirit of place" (to borrow a phrase from D. H. Lawrence) is civility, or at least the desire to appear civil in public, which is saying a great deal. The people—and especially artists—in this region tend to be highly independent and tolerant. My former student and native Northwesterner David Guterson, author of the best-selling novel Snow Falling on Cedars, recently told me that the people who first journeyed this far west—so far that if they kept going they'd fall into the Pacific Ocean—came mainly to escape other people. Their descendants are respectful of the individual and of different cultural backgrounds and at the same time protect their privacy. They acknowledge tradition but don't feel bound by it. As physically far removed as they are from cultural centers in New York, Boston, Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles (the distance from those places is both physical and psychic), they are not inclined to pay much attention to fashions or the opinions of others and instead pursue their own singular visions. I'm thinking of people like Bruce Lee, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain, Ray Charles in the late 1940s; playwright August Wilson; artists such as Jacob Lawrence and George Tsutakawa; and writers such as Sherman Alexie, Octavia Butler, Timothy Egan, Theodore Roethke and his student David Wagoner (serial killer Ted Bundy once took one of his poetry workshops). Jonathan Raban, an immigrant from England, captures the ambience of this book-hungry city perfectly:

"It was something in the disposition of the landscape, the shifting lights and colours of the city. Something. It was hard to nail it, but this something was a mysterious gift that Seattle made to every immigrant who cared to see it. Wherever you came from, Seattle was queerly like home....It was an extraordinarily soft and pliant city. If you went to New York, or to Los Angeles, or even to Guntersville [Alabama], you had to fit yourself to a place whose demands were hard and explicit. You had to learn the school rules. Yet people who came to Seattle could somehow recast it in the image of home, arranging the city around themselves like so many pillows on a bed. One day you'd wake up to find things so snug and familiar that you could easily believe that you'd been born here."

In other words, this is an ideal environment for nurturing innovation, individualism and the creative spirit. (Those words are probably somewhere in the mission statement for Microsoft, which in 1997 sent me for two weeks to Thailand to write about "The Asian Sense of Beauty" and whose campus is just a 25-minute drive from my front door.) Here we find poetry in the lavish scenery right outside our windows, which dwarfs, predates and no doubt will long outlive everything we write about it. The mountains rise up to 14,000 feet above the sea. There are magnificent, rain-drenched forests, treeless desert lands, glacial lakes, some 3,000 kinds of native plants and hundreds of islands in Puget Sound: an enveloping landscape as plentiful and prolific on its enormous canvas as I suppose we as artists would like to be on our smaller ones. Thus, it has always struck me as fitting that Sea-Tac was among the first airports in America to set aside a room specifically for meditation. (After traveling through Puget Sound or visiting the waterfront in Pioneer Square, you need to sit quietly for a while and savor being so delightfully ambushed by such beauty.)

The Pacific Northwest's geographic diversity, its breathtaking scale and our Lilliputian niche in the shadow of such colossi as Beacon Rock on the Columbia River or majestic Mount Rainier humble a person's ego in the healthiest way. It reminds me of my place as one among uncountable creatures in a vast commonwealth of beings that includes the Canada lynx, bobcat, white-tailed ptarmigan and quail. It never fails to deflate my sense of self-importance. It tips me easily toward a feeling of wonder and awe at this overly rich and inherently mysterious world in which I so fortunately find myself.

If you're standing, say, on Orcas Island, you can see whales cavorting in viridian waves, and the air out there on the islands is so clear, so clean, that each breath you draw feels like some sort of blessing. This sort of Northwest experience helps me take the long view on life's ephemeral problems. Need I add that this opportunity to step away from the hectic pace and cares of city life whenever one wishes is a stimulus for art, philosophy and spiritual contemplation? And all those inward activities are enriched by the misty, meditative mood invoked by the Northwest's most talked about feature—rain—and the wet evening air that causes portions of the geography to gleam and hazes other parts, sfumato, from November through February, in an atmosphere that is a perfect externalization of the brooding inner climate of the creative imagination. As a child growing up in Illinois, I shoveled snow. Here, you might say, we shovel rain, but with weather like this, it's easy to stay inside, reading and writing, until spring.

Being a transplant like Raban and a Buddhist practitioner means that even after living here for more than half my life, I don't take the gift of this beauty—nor the room to stretch out spirit and body—for granted. I don't mean that metaphorically. I taught kung fu for ten years at Phinney Neighborhood Center, sharing that space with a yoga class, and our students at one time included a scientist, an architect, UW professors and a Zen abbot. My wife, Joan, born and raised on Chicago's South Side in a sometimes violent housing project called Altgeld Gardens, and I happily raised our children here. They can truly call this place—accurately described as a "city of neighborhoods"—home. On Capitol Hill two years ago, our daughter, Elisheba, a conceptual artist, opened Faire Gallery/Café, which features jazz performances and the occasional play or open-mic poetry night as well as art shows and comedy performances by young local talent. Faire is where I hang out these days, conducting my classes and keeping appointments in a vibrant atmosphere—straights and gays, students and goths—that recalls the freewheeling creative vitality of Berkeley in the late 1960s.

For Seattle is, whatever else, a place where the young, single, iconoclastic and open-minded seem to thrive. Remembering Gardner's words from three decades ago, I imagine he would give that same advice today. The Rev. Samuel McKinney, once pastor of Mount Zion Baptist, the largest black church in the region, was a Morehouse College classmate of Martin Luther King Jr. and invited him to Seattle in 1961. On March 12, 2007, King County (where I live) changed its official logo from an imperial crown to an image of the great civil rights leader; MLK joins Chief Sealth (Seattle), who represents the city, and George Washington, avatar on the state's seal.

Were he alive today, King might not describe the Pacific Northwest as the Promised Land, but I believe he would be pleased by how Seattle's citizens—however imperfect we may be—strive to realize his dream of a "beloved community" in a city poised at the edge of the nation's western end.

Charles Johnson recently collaborated on Mine Eyes Have Seen: Bearing Witness to the Civil Rights Struggle.