How a Missile Silo Became the Most Difficult Interior Decorating Job Ever

A relic from the Cold War, this instrument of death gets a new life … and a new look

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Missile-before-after.jpg)

Mushroom clouds never figured into the nightmares of Alexander Michael. He was 4 years old during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 and, as a kid in Sydney, Australia, he says, "all the action in the U.S. was far enough away from us … to be amused by the goings-on, not afraid, as we didn’t really understand the scale and consequences.”

Meanwhile, halfway across the globe, Richard Somerset, a 21-year-old U.S. Air Force airman training to become a ballistic missile analyst technician, was well aware of the threat of nuclear war. Within a few weeks of the end of the crisis, he was stationed at Plattsburgh Air Force Base in northeastern New York and assigned to an Atlas F missile silo in the sparsely populated Adirondack town of Lewis.

Forty-five years later, long after the Cold War had ended, the Lewis missile silo brought these two unlikely men together.

********

The silo was one of a dozen within 100 miles of Plattsburgh Air Force Base. Completed in 1962, the 12 sites cost the U.S. government well over $200 million and two-and–a-half years of round-the-clock construction to erect—if erect is the right word for structures bored 180 feet into the earth. Somerset was on a crew of five that worked 24-hour shifts—one day on, two off—inspecting and maintaining the systems and waiting for the signal they hoped would never come.

One day in late 1964, Somerset was at the missile control console when the hair stood up on the back of his neck—a war code had come through on the radio. “Uh oh,” he recalls thinking, “Here we go.” To his relief, he quickly learned it had been a false alarm—the code format had changed and Somerset hadn’t been briefed—but those few moments were the closest he came to a test of his willingness to launch a weapon that could wipe out an entire city.

“I don’t think anyone on the crew ever felt we wouldn’t be able to do it if the time came,” he says. He points out that for people of his generation, Nazi atrocities were fresh history and they feared the Soviets had equally sinister intentions. To alleviate any feelings of guilt, the crewmen were never told the programmed destination of their missile. But they had been told that the weapon was only to be launched in retaliation for a Soviet strike, so if they were called upon to deploy it, they believed they were doing so to prevent large-scale American casualties. “I am extremely proud to have been part of it,” Somerset says.

In 1965, less than three years after they were installed, the Atlas F missiles were already deemed obsolete and were decommissioned. Somerset and the rest of the crew were reassigned and the Lewis silo, like the others nearby, sat unused and deteriorating for decades. Some were sold cheaply to local municipalities or bought by private owners who used the aboveground storage facilities or salvaged scrap metal from the silos. Most people saw the sites as Cold War relics of little value, but not Alexander Michael.

As an adult in Sydney, Michael became an architect/designer with a fascination for industrial structures. In 1996, he read a magazine article about a man named Ed Peden who lived under the Kansas prairie in a decommissioned Atlas E missile silo Peden called Subterra. Michael had grown up on American books and movies of the nuclear age, and he was enchanted by the idea of having his very own piece of military-industrial history. “I rang [Peden] up and told him how cool he was,” Michael says. “A couple weeks later he called and told me about this silo [that] was available.”

Michael’s friends thought he was crazy when he flew halfway around the world to buy a dank, decrepit 18-story hole in the ground in the Adirondack Mountains. When he got to the site in Lewis on a frigid December day in 1996 and saw the condition of the place, he was inclined to agree with them. “The wind was howling, it must have been a hundred below. It was hideous,” he recalls. The enormous steel and concrete doors to the silo had been left open for years, and the hole had filled partway with water, now turned to ice and snow. Everything was filthy and covered in rust and peeling paint.

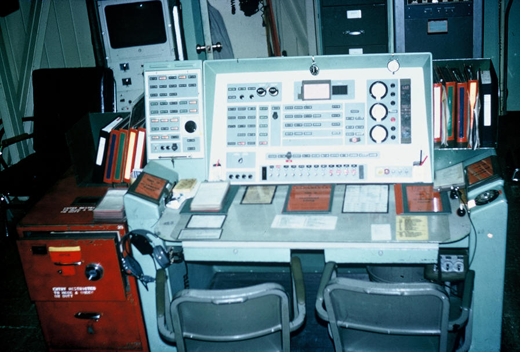

But compared with other sites that had been flooded and pillaged beyond recognition, the control center in this one—attached to the silo by a 40-foot tunnel—was in relatively good shape. Even the launch console was still intact, red button and all. Against his better judgment, Michael went through with the sale, paying $160,000 for the structure and its eight acres; he sold an apartment building he owned in Sydney to pay for it.

So began a massive restoration project that continues today. Over three-week visits each spring and fall, Michael has gradually turned the silo control center into a living space that comes close to, or at least pays homage to, its historical state. In September, a regional architectural heritage organization gave him a historical preservation award for his “long-term stewardship” and “sensitivity to the structure’s original purpose and period.”

About five years ago, Richard Somerset contacted Michael and came to see his old workplace for the first time since the 1960s. "It was exciting and yet extremely depressing,” says Somerset. “We all have memories, and then to see the deterioration of the site to the point that—how could this happen?"

“Dick was deeply upset when he first visited the site and saw the condition it was in,” Michael recalls. “He was probably lucky not to see it before I started work.”

Michael has done much of the renovation himself—no small feat. “The scale and the strength and the proportions of everything here are so enormous and so big that you can’t deal with them with domestic tools or domestic strength,” he says. “Everything has to be ten times bigger. … Things go awry so easily.”

For instance, in 2011, after scouring salvage yards for years, he finally found a replacement for the hydraulic rams that opened and closed the 90-ton silo doors. Last fall he assembled friends to watch as he closed the doors for the first time in decades. Partway down, one of the rams started spewing hydraulic fluid.

Michael has been more successful in the control center. You enter the space by descending a 40-foot staircase to the entrapment vestibule and a pair of 2,000-pound steel blast doors. The two-level control center is a 45-foot-diameter cylinder; in the center is a huge fan-vaulted concrete support column. The floors do not connect to the walls; instead, a system of four pneumatic arms was designed to absorb the shock of a direct nuclear hit. An overhead escape hatch in the top level is filled with four tons of sand, also to absorb shock. In the event a nuclear blast blocked the main entrance, the top few inches of sand would turn to glass from the extreme heat; the crew members would open the hatch to let out the rest of the sand, use a hammer to break through the glass and crawl out.

The decor is full of cheeky references to the silo’s past purpose, with a color scheme that is mostly utilitarian gray, orange and blue. A set of clocks on one wall displays the times in world cities. In the kitchen is a stack of aluminum mess kits left over from a military-themed party Michael once threw. Flight suits hang on a wall in the bedroom, the former missile control room, where he has also painted a round table with a yellow and black radiation symbol. The original launch console is still there, though, to Michael’s great disappointment, on his first return visit after the purchase he discovered the red button had since been stolen. (As it turns out, it wasn’t the launch commit button anyway—according to Somerset, the real one was kept under a flapper cover to avoid accidental activation. The red button was to sound the klaxon that would alert the crew to prepare for a launch.)

Since there are no windows, Michael has mounted a closed-circuit television to the wall so he can see what’s happening outdoors. The temperature in the control center is a constant 55 degrees; it takes a good two weeks of running the heat pump full time to bring it up to 68. But the most marked difference of living below ground instead of above is the utter silence. “I remember one night I got up out of bed thinking, there’s something humming, and I had to find it,” he says. He looked high and low for the source of the noise. “I eventually gave up and went back to bed. I finally realized it was just the buzz in my head. It’s that quiet.”

Since the 9/11 attacks, a flurry of interest in the remote, bombproof sites has left Michael feeling both vindicated and slightly unsettled. He says he has been approached by groups wanting to buy his place as a haven in which to wait out the “end times.”

Ed Peden, the Kansas man who directed Michael to his silo, operates a website advertising other missile sites for sale around the country. Many converted silo homes have been made to look like regular houses inside, with back-lit false windows, modern kitchens and other homey touches. One, an above- and below-ground luxury log home about 45 miles from Michael’s silo, includes its own airstrip and is on the market for $750,000. People have also found novel uses for the underground structures, as a scuba diving center (near Abilene, Texas); a one-man UFO investigation center (near Seattle); and, until it was raided by the Drug Enforcement Agency in 2000, an illicit drug lab that produced one-third of the nation’s LSD.

Michael has also found creative ways to take advantage of his silo’s unique space. It’s been used as a film set several times. Last fall during an open house, he staged a sculptural installation called Rapture, inspired by the doomsday groups that have contacted him. Later this month, three engineers will stage an interactive LED light show inside the main chamber of the silo.

Michael’s dream is to complete the restoration of the silo and turn it into a performance space—the acoustics are fantastic, he says. He is seeking a financial partner because, after spending an estimated $350,000 of his own money on renovations over the years, he is tapped out.

But he has no regrets. “In terms of joy and excitement and happiness,” he says, “it has paid for itself a thousand times over.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Bramen-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Bramen-240.jpg)