Hill of Beans

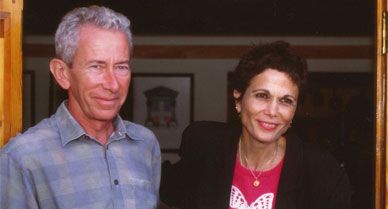

For author Julia Alvarez and her husband, starting an organic coffee plantation was a wake-up call

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/coffee631.jpg)

Eleven years ago, the Dominican-American writer Julia Alvarez traveled through the Dominican Republic's western mountain region, the Cordillera Central, to write a story about the area for the Nature Conservancy. Near the town of Jarabacoa, Alvarez and her husband, Bill Eichner, met a group of struggling farmers growing coffee the traditional way—without the use of pesticides and under shade of trees. In doing so, the organic farmers were bucking a trend at larger area plantations of clearing hillside forests to plant more crops, which destroyed the natural habitat of migratory songbirds and damaged the soil with pesticides and erosion. But they needed help.

Alvarez and Eichner offered to make a donation, but the farmers had something else in mind. They asked the couple to buy land they could farm, to help export their coffee to the United States.

Alvarez, author of books including How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents and the recent Once Upon A Quinceañera, remembers her first reaction was to ask, incredulously, "How?" The couple lived in Vermont, not to mention that neither Alvarez nor Eichner, an ophthalmologist, knew anything about coffee farming.

"I didn't even know there were berries that turned red," says Alvarez, referring to the cherry-like fruit that reddens as it ripens and holds a seed commonly known as a coffee bean. "I had no idea coffee comes from poverty. Like most people in the First World, I just wanted it in my cup in the morning." In the Dominican Republic and other developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, Alvarez learned, life is a struggle for many coffee farmers, whose success depends on the fluctuating price of their crop.

For Eichner, the question wasn't one of practicality. It was: "How can we not?" Eichner grew up on a Nebraska farm and witnessed first hand its demise as the land was bought by businesses and consolidated into larger farms in the 1960s. He saw the Dominican farm as a way to give back to the developing country of Alvarez's childhood, and to make a small difference in the lives of the farmers and the Dominican environment.

In 1996, after a bit of persuasion that Alvarez describes as "being dragged kicking and screaming," the couple purchased their first parcel of abandoned farmland some 30 minutes up a windy, country road outside of Jarabacoa. Over the next two years, they bought more land until they had a 260-acre farm, which they named Finca Alta Gracia, after the Dominican Republic's patron saint, Altagracia, or High Grace.

To the untrained eye, the coffee fields at Alta Gracia look like an overgrown jungle. Growing up and down terraced mountainsides, the coffee plants with their small, shiny leaves and spindly branches hold berries in different stages of maturation: some are green, some are pink. When these berries, which contain the precious coffee bean, turn bright red during the harvest period from November to April, they are picked by hand. Overhead is a canopy of leafy Guamas, native pines and lush banana trees. Scratching and pecking at the ground is a large group of free-range chickens.

Everything in this seeming chaos has a purpose and is the result of more than a decade of re-foresting and re-planting, Yosayra Capella Delgado, a farm employee, explained to me on a recent visit. The coffee plants, which can take up to four years to produce their first harvest, are a mix of three varieties of arabica. The trees, with their various heights, provide levels of shade that help the coffee mature slowly, enhancing its flavor. Their leaves also provide nourishing mulch.

For the farm's first eight years, Alvarez and Eichner managed things from Vermont, visiting every few months. When the plants first began to bear coffee cherries, the couple transported duffel bags full of beans back to the states to roast and give to friends. Eventually they began to sell their coffee. For Alvarez, one of the first strokes of serendipity was when they teamed up with Paul Raulston, the owner of the Vermont Coffee Company, after Eichner met him at a meeting about coffee roasting. Raulston now roasts the coffee and distributes it under his Café Alta Gracia and Tres Mariposas labels.

The response has been phenomenal. "The coffee is just so good, we've always been able to sell out of it," says Raulston, likening its taste to the Blue Mountain coffee from Jamaica. He currently imports and roasts about 16,000 pounds of Alta Gracia coffee a year—some 500,000 cups.

As farm operations progressed, its owners realized that they wanted to do more for the twenty or so coffee farmers and their families, besides paying them fair wage—around twice the region's average. None of the farmers or their children knew how to read or write. So Alvarez and Eichner arranged to build a school and library at Alta Gracia.

In A Cafecito Story, Alvarez's 2001 book inspired by her experience with the farm, she sums up this dual importance of sustainable farming and literacy in one lyrical sentence: "It's amazing how much better coffee grows when sung to by birds or when through an open window comes the sound of a human voice reading words on paper that still holds the memory of the tree it used to be."

In 2004, weary from years of managing from a distance, Alvarez and Eichner learned from one of Alvarez's uncles that the Dominican Institute for Agriculture and Forestry Research, a governmental non-profit, was looking for a regional research center and demonstration farm. For the past three years, the institute's employees have managed Alta Gracia and used it as a training facility where, among other experiments, they've developed natural ways of controlling the dreaded coffee broca—a poppy-seed sized pest that ravages coffee cherries across the Caribbean and Latin America. Educational workshops are frequently held at the farm office and the visitor center.

Meanwhile, back in Vermont, Alvarez and Eichner are looking into ways to keep their farm going long after they are gone. "Our goal is to pass it on," Alvarez says. The couple is hoping to find for a U.S. university interested in taking over Alta Gracia. "It's 260 acres on a Third World mountain," Alvarez says. "This is a place that can be an environmental learning center. It's a new kind of learning, beyond walls."

Emily Brady lives in Brooklyn and writes regularly for the New York Times.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/eric-jaffe-240.jpg)