Escaping the Iron Curtain

Photographer Sean Kernan followed Polish immigrants Andrej and Alec Bozek from an Austrian refugee camp to Texas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Andrej-Bozek-Alec-Sean-Kernan-631.jpg)

In the spring of 1974, Andrej Bozek came up with a plan so risky that he kept it even from his wife. "She probably would have gone to the police," he says.

"I probably would have," Irene Bozek agrees. "I thought it was much too dangerous."

Andrej, a bus-factory worker in the battle-worn Polish city of Olawa, wanted desperately to get Irene and their three children out from under the repression of the country's Communist regime. But to discourage defection, the Polish government almost never allowed families to leave together, and the Iron Curtain was heavily guarded. So Andrej plotted to take his youngest child, 3-year-old Alec, on a legal, ten-day vacation to Austria—then seek asylum at a refugee camp in the town of Traiskirchen, 15 miles south of Vienna. He would take his chances on whether the Polish government would let the rest of his family follow.

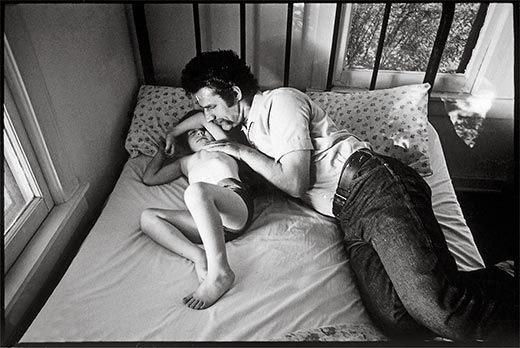

It was at Camp Traiskirchen that photographer Sean Kernan and I met Andrej and Alec, while preparing to make a documentary film for CBS-TV about families emigrating to the United States. The camp's atmosphere was laced with resignation and fear, but the Bozeks were different. "Even in their stateless condition, Andrej seemed calm, almost confident," Kernan recalls. Alec was beguiling and "seemed completely comfortable in the world. He didn't complain and he immediately engaged with everyone and everything."

In the United States, it was the high season of Watergate, and the refugee camp echoed with rumors of an imminent U.S. government collapse. The Bozeks, who spoke no English, were unfazed. With the guidance of an English-speaking refugee, they spent hours studying a children's book of United States history.

Rumors of collapse notwithstanding, the U.S. government would receive more than 130,000 refugees the next year. In December 1974, after five months at Traiskirchen, the Bozeks' wait was suddenly over: Andrej received a letter that began, "You have been accepted by the United States of America."

He told his wife the news in a letter, just as he had told her of his defection, promising that the family would be reunited in the United States—eventually. Irene was not mollified. "I was so angry with him...that he took away my baby, and I might not be able to see them," she recalls. "I was crying and I was mad."

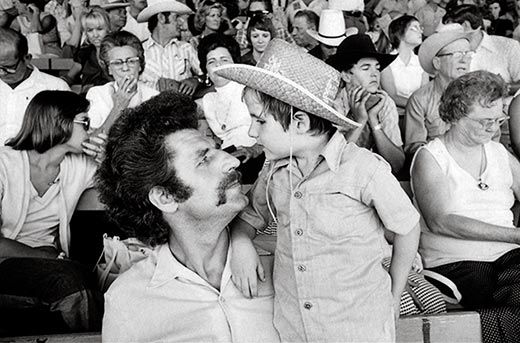

Andrej and Alec arrived in New York City on January 29, 1975. A refugee agency sent them to Perth Amboy, New Jersey, where they shared, with another refugee, a room over a Polish bar. Work and child care were scarce. After about four months, a regular at the bar advised Andrej to "go west." Research by Helen Whitney, an associate producer of our film, led him to Fredericksburg, Texas, west of Austin. Within days of arriving, "Andy" had a new name and a job in construction, and "Alex" had playmates, cowboy boots and a bevy of surrogate mothers.

That July, Irene applied for Polish passports for herself, her 12-year old-son, Darius, and her daughter, Sylvia, 5. "The man at the police station said, ‘Forget that,' " she says. She went to the U.S. consulate in Warsaw to seek visas, and an official there told her that her husband's participation in our film—which the State Department knew about—would doom her chances of getting out of Poland. "This was the first time I had heard about a movie," Irene says. "That depressed me even more." Still, she reapplied to the Polish government for a family passport.

On August 4, 1976, CBS broadcast To America, featuring Andrej and Alec Bozek and two other emigrant families from Poland.

In early September, the police summoned Irene Bozek.

"When I go in, it is the same man who told me ‘no' before, but now he is smiling and very friendly to me," she says. He told her to apply for the passports in Wroclaw, 18 miles away. She was euphoric. "I was flying from the stairs of that police office, so high I don't know how I will get down," she says. Visas from the U.S. consulate in Warsaw followed. No one has ever offered an official explanation for the Polish government's sudden change of heart.

Thus the Bozek family was reunited on November 28, 1976. Amid the crowd at New York City's Kennedy International Airport, which included our camera crew, Irene spotted Andy before he spotted her. He was wearing a ten-gallon hat.

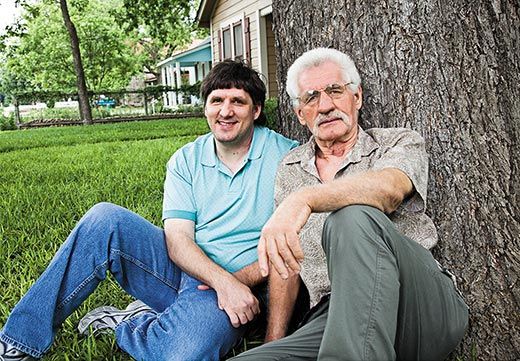

Today, Andy Bozek, 71, is retired from the Texas highways department, where he worked for 18 years. Irene, 63, works for a custom bookbinder in Austin, where they own a house. They raise and sell tropical fish. Darius, 45, is vice president of a fish-food company in Southern California, where he lives with his partner, Thea, and their 3-year-old son, Darius. Sylvia, 39, lives with her parents and maintains tropical aquariums for clients. Alec, 38, also lives in Austin, with his wife, Nicole. He is seeking work, having been laid off last October from a job assembling tools for making semiconductor chips.

"If it had been me, we would still be in Poland," Irene says. "I am the worrier. Andy, he never worries about nothing."

"I know my plan would work for whole family," he says. "And now you can see right here."

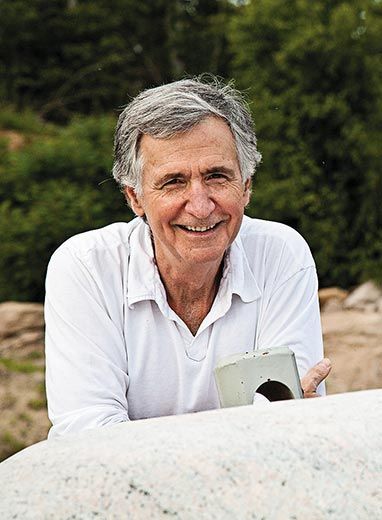

Dewitt Sage has been a documentry filmmaker since 1968. His most recent film is Ernest Hemingway, Rivers to the Sea.