Digging Ditches

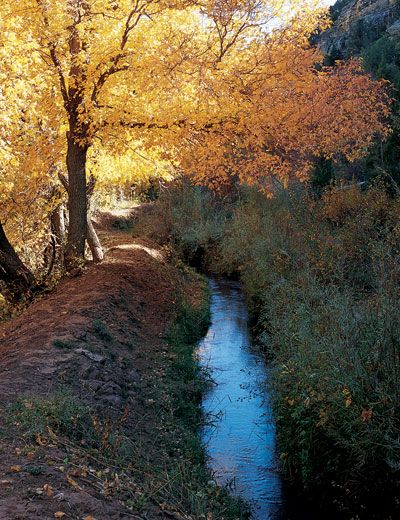

Narrow, humble irrigation ditches called acequias sustain an endangered way of life but for how long?

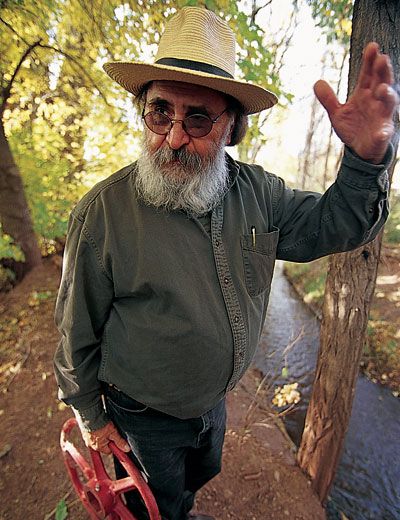

Often barely three feet wide and half that deep, the lowly acequia is a hand-dug, lovingly maintained ditch. Built by Spanish colonizers in the 17th and 18th centuries, acequias were once the lifelines of many rural Hispanic communities from Texas to California.

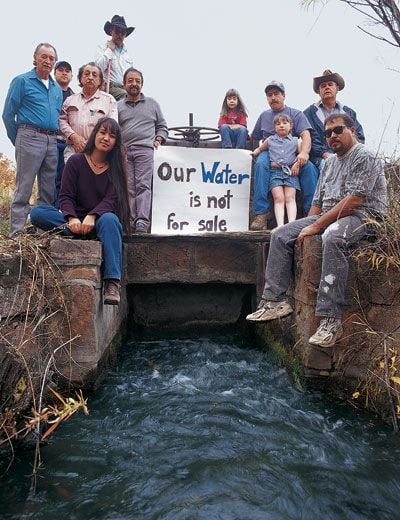

But now they are dried up, or mere curiosities, everywhere but in northern New Mexico (plus a few places in southern Colorado), where more than a thousand still survive. In this proudly ethnic region, where every valley seems to have Apodacas, Montoyas and Martinezes who have farmed the same land since before the Civil War, acequias are community traditions, among the oldest public works projects in America.

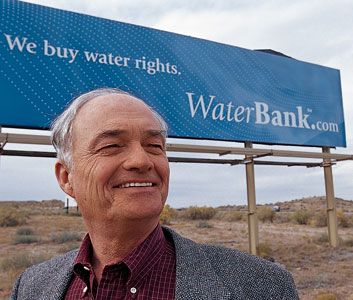

These ancient rivulets, however, are now under siege. As water has become an increasingly precious commodity throughout the Southwest, families holding rights to a particular acequia are sought out by water brokers or developers, in search of water for golf courses and resorts, for example. In some villages north of Santa Fe, rights to an acre-foot of water, the amount needed to cover one acre with one foot of water, are going for a onetime fee of $30,000 to $40,000.

Acequia loyalists have good reason to fear for their culture. "When I tell older people in these communities that you can actually buy and sell water rights," maintains one local activist, "they can't believe it. They say it's like selling sunshine."