Cowboys and Immigrants

Two dueling archetypes dominated 20th-century American politics. Is it time for them to be reconciled?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ellis-Island-immigrants-The-Searchers-631.jpg)

At Fort Clark in West Texas one night in the 1870s, my great-grandmother Ella Mollen Morrow was asleep in the officers' quarters. Her husband, Maj. Albert Morrow, was several days' ride away, on patrol with his troop of Fourth U.S. Cavalry. A soldier, probably drunk, crawled into the house through a window. My great-grandmother heard him. She took up a Colt .44 revolver and warned him to get out. He kept coming at her. She warned him again. The man kept coming.

She shot him—"between the eyes," as a family history said, adding, "No inquiry was held, or deemed necessary."

That was the frontier, all right, and I confess that during the presidential campaign last fall, Sarah Palin—moose hunter, wilderness mom—stirred, for a moment anyway, a genetic current of admiration in my heart. It was an atavistic memory of Ella, of her self-sufficient smoking pistol and its brisk frontier justice, which, on that night in West Texas, pre-emptively brought the bad guy down, dead at her feet. No nonsense.

At the time, the McCain-Obama campaign seemed a clash of neat American opposites. John McCain (maverick, ex-fighter pilot, military hero, senator from Geronimo country), with his sidekick Palin (chirpy backwoods deadeye), worked the Frontier story line. Barack Obama came onstage as apotheosis, the multiracial, multicultural evolution of what Ellis Island promised to the Nation of Immigrants long ago.

But in the evolving financial shambles of the months since the election, the conflict between these mystic poles of American history appeared to vanish, or to dissolve in a chaotic nonideological synthesis. Both Ellis Island and the Frontier hated Wall Street, just as passengers in steerage and passengers in first-class unite in despising icebergs. And amid the great federal bailouts, Newsweek proclaimed, "We Are All Socialists Now."

I wonder. The Frontier and Ellis Island are myths of origin, alternate versions of the American Shinto. They're not likely to disappear anytime soon.

The two myths are sentimental and symbolic categories, no doubt—ideas or mere attitudes more than facts: facets of human nature. (Quite often, when given a hard look, myths fall apart: the historical frontier, for example, was demonstrably communitarian as well as individualist). But like the philosopher Isaiah Berlin's Hedgehog and Fox or literary critic Philip Rahv's Paleface and Redskin, they offer convenient bins in which to sort out tendencies.

Both myths owe something of their vividness to Hollywood—one to the films of John Ford and John Wayne, for example, and the other to Frank Capra's parables of the common man. The Frontier is set on the spacious Western side of American memory—a terrain whose official masculinity made my great-grandmother's, and Palin's, Annie Oakley autonomies seem somehow bracing. On the other side (diverse, bubbling away in the "melting pot," vaguely feminine in some gemütlich nurturing sense) lies Ellis Island. If Frontier dramas call for big skies, open space and freedom, Ellis Island's enact themselves in cities; their emphasis is human, sympathetic, multilingual and noisy, alive with distinctive cooking smells and old-country customs. The Frontier is big, open-ended, physically demanding, silent.

This bifurcation of American consciousness occurred with a certain chronological neatness—a development "unforeseen, though not accidental," as Trotsky might have said, working his eyebrows. Ellis Island opened for business in 1892 as the gateway for the first of some 12 million immigrants. One year later, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his "frontier thesis" before the American Historical Society at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. When the Pacific Ocean halted the American frontier on the West Coast, Turner argued, the distinctive urgencies of American destiny closed down. But at just that moment, the East Coast opened up to a powerful flow of new immigrant energies.

In the years 1889-96, the gun-toting ranchman-intellectual Theodore Roosevelt published his four-volume history, The Winning of the West. The evolution of the Frontier mythology was in some ways an instinctive reaction against all those foreigners. Ellis Island made the Frontier feel claustrophobic, just as the arrival of sodbusters with their plows and fences would incense the free-range cattle people.

Starting with Teddy Roosevelt, these two American archetypes have reappeared from time to time as presidential styles and ideological motifs. T.R., the sickly New York City boy who repaired health and heart in the Dakota Badlands, was the first modern Frontier president.

His dramatization of Frontier attitude occurred at the moment of the Spanish-American War, of Senator Albert Beveridge's triumphal jingo about "The March of the Flag." In 1899, sixteen of Teddy's Rough Riders joined Buffalo Bill Cody's touring Wild West show. Gaudy Wild Bill in fringed buckskins told an audience at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha: "The whistle of the locomotive has drowned the howl of the coyote; the barb-wire fence has narrowed the range of the cow-puncher; but no material evidence of prosperity can obliterate our contribution to Nebraska's imperial progress." Imperial Nebraska! When the Frontier grew grandiloquent, it sounded like a passage of Ned Buntline as recited by W. C. Fields.

But in Frontier rhetoric there was often a paradoxical note of elegy and loss, as if the toughest place and moment of the American story was also the most transient, most fragile. By 1918, the Old Bull Moose, reconciled to the Republican Party, was condemning the "social system...of every man for himself" and calling for worker's rights, public housing and day care for the children of mothers working in factories. In nine months, he was dead.

The other Roosevelt, T.R.'s cousin Franklin, became the first Ellis Island president. He came to office not at a moment when America had seemed to triumph, but when it had seemed to fail. In myth, if not in fact, the Frontier sounded the bugle—cavalry to the rescue. Ellis Island's narrative began with Emma Lazarus' disconcerting, hardly welcoming phrases of abjection—"your tired, your poor...the wretched refuse..." Its soundtrack was the street sounds of the pluribus.

John Kennedy—by way of Choate, Harvard and his father's money—claimed to be working a "New Frontier," and though he campaigned as a cold warrior in 1960, he did break new ground with the Peace Corps and the space program and his American University speech on nuclear disarmament. But in memory the New Frontier seems mostly to refer to a generational takeover, more a Sorensen trope in the service of generational ambition than a true departure.

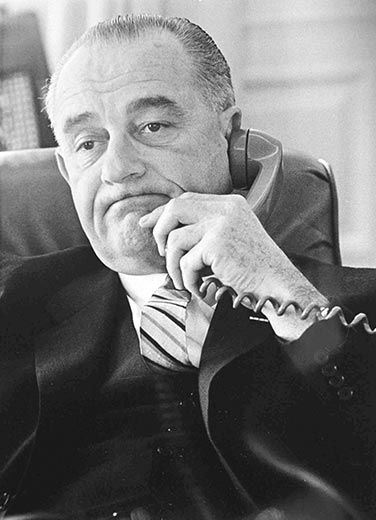

One of the things that made Lyndon Johnson interesting was that he so thoroughly embodied both the Frontier and Ellis Island—and tried to enact both, in the Great Society and in Vietnam. Perhaps it was the conflict between the two ideals that brought him down. A son of the Texas hill country, with its lingering folklore of the Alamo and of long-ago massacres under the Comanche moon, Johnson was also a New Deal Democrat and FDR protégé with all the activist-government Ellis Island instincts. In an interplay of Ellis and the Frontier, he actually tried to bomb Ho Chi Minh into submission while offering to turn Vietnam into a Great Society, full of New Deal projects (dams and bridges and electrification), if only Uncle Ho would listen to reason.

At the Democratic National Convention in 1984, the perfect Ellis Island man, Gov. Mario Cuomo of New York, conjured up a sweet America that originated in sepia photographs of ships arriving in New York Harbor, the vessels' rails crowded with the yearning faces of people from a dozen countries over there, at the instant of their rebirth, their entry into the American alchemy that would transform them and their children forever. "We speak for the minorities who have not yet entered the mainstream," this son of Italian immigrants proclaimed. "We speak for ethnics who want to add their culture to the magnificent mosaic that is America." He called up Ellis Island that summer of 1984 at the same moment Ronald Reagan of California convinced Americans that they were tall in the saddle again, riding into the sunshine of a new morning in America. The Frontier won that round, by a landslide.

Reagan personified the cowboy universe that sees itself as self-reliant, competent, freedom-loving, morally autonomous, responsible. He owned a ranch and wore cowboy clothes, and in the Oval Office he displayed a passel of sculptures of cowboys and Indians and bucking broncos. In Reagan's exercise room in the family quarters of the White House, his wife, Nancy, had hung a favorite Reagan self-image, a framed photograph showing him in bluejeans and work shirt and shield-size belt buckle and a well-aged, handsomely crushed white cowboy hat: Reagan's eyes crinkle at the far horizon. The photo watched from the wall as President Reagan pumped iron.

George W. Bush put himself in the Reagan mold. Barack Obama's victory represented, among other things, a repudiation of the Frontier style of Bush and Dick Cheney, in favor of an agenda arising from the Ellis Island point of view, with its emphasis on collective social interests, such as health care and the environment. A civic paradigm seemed to have shifted, and a generational paradigm as well.

And yet the future (Obama's hopeful young constituency) found itself boomeranged back to the Great Depression. The simultaneous arrival of Obama and bad financial times elicited perhaps too many articles about Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal. Implicitly, George W. Bush and the Frontier way of doing things seem as discredited today as Herbert Hoover seemed in 1933.

Newsweek's proclamation notwithstanding, my guess is that the categories of Ellis Island and the Frontier persist—but now, like so much else, have been globalized.

In the 21st century, the division between the two mind-sets projects itself into McLuhan's misnamed "global village," which, more accurately, has become a planetary megacity with some wealthy neighborhoods (now not as wealthy as they thought they were) and vast slum districts—a megacity without police force or sanitation department. The messy municipal planet remains in many ways a frontier, a multicultural Dodge City or Tombstone (lawless, with shooting in the streets, dangerous with terrorism and nuclear possibilities, not a fit place for women and children) that has an Ellis Island aspiration to survive and prosper as the family of man.

The Frontier and Ellis Island analyze problems in different ways and arrive at different decisions. The Frontier assumes the drunken soldier is a rapist or murderer and shoots him between the eyes. Ellis Island may see him as a confused fool and hope to talk him into a cup of coffee and a 12-step program. Roughly the same choices present themselves to a president: the planet is the Frontier; the planet is Ellis Island. Genius is the ability to hold two contradictory truths in the mind at the same time without going crazy.

Obama might reflect upon the transition of Harry Hopkins, FDR's inside man and chief federal relief dispenser during the New Deal. Hopkins was the most abundantly generous of Keynes-ian do-something-now bleeding hearts, with a heart as big as Charles Dickens'. After Hitler took Poland and France and started bombing London, Hopkins became one of Roosevelt's most aggressive and efficient war facilitators, organizing lend-lease and acting as FDR's emissary to Churchill and Stalin. Hopkins abandoned Ellis Island for the Frontier. He complained that his New Deal friends—during the Battle of Britain, before Pearl Harbor—did not understand the change that had come over him.

Hopkins was, of course, the implementing instrument and executive echo of Franklin Roosevelt, an Ellis Island president who, after December 7, 1941, found himself confronting history's wildest frontier.

Lance Morrow, author of The Best Year of Their Lives (2005), is writing a biography of Henry Luce.