Seven All-American Curiosities

Seven All-American Curiosities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/odd-museums-Historic-Voodoo-Museum-631.jpg)

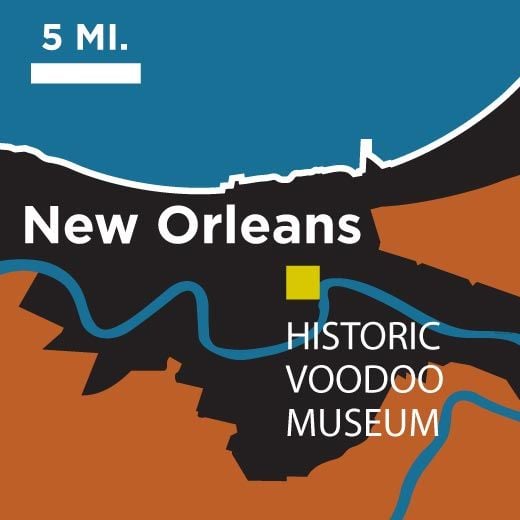

New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

New Orleans, Louisiana

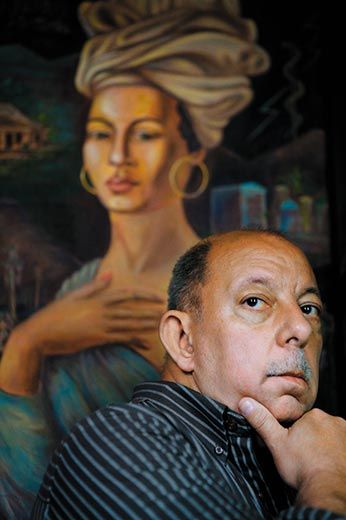

Jerry Gandolfo didn’t flinch when a busload of eighth-grade girls began shrieking at the front desk. The owner of the New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum simply assumed that John T. Martin, who calls himself a voodoo priest, was wearing his albino python around his neck as he took tickets. A few screams were par for the course.

Deeper in the museum it was uncomfortably warm, because the priest has a habit of turning down the air conditioning to accommodate his coldblooded companion. Not that Gandolfo minded: snakes are considered sacred voodoo spirits and this particular one, named Jolie Vert ( “Pretty Green,” although it is pale yellow), also furnishes the little bags of snake scales that sell for $1 in the gift shop, alongside dried chicken feet and blank-faced dolls made of Spanish moss.

A former insurance company manager, Gandolfo, 58, is a caretaker, not voodoo witch doctor—in fact, he’s a practicing Catholic. Yet his weary eyes brighten when he talks about the history behind his small museum, a dim enclave in the French Quarter half a block off Bourbon Street that holds a musty jumble of wooden masks, portraits of famous priestesses, or “voodoo queens,” and here and there a human skull. Labels are few and far between, but the objects all relate to the centuries-old religion, which revolves around asking spirits and the dead to intercede in everyday affairs. “I try to explain and preserve the legacy of voodoo,” Gandolfo says.

Gandolfo comes from an old Creole family: his grandparents spoke French, lived near the French Quarter and rarely ventured beyond Canal Street into the “American” part of New Orleans. Gandolfo grew up fully aware that some people swept red brick dust across their doorsteps each morning to ward off hexes and that love potions were still sold in local drugstores. True, his own family’s lore touched on the shadowy religion: his French ancestors, the story went, were living in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) when slave revolts convulsed their sugar plantation around 1791. To save Gandolfo’s kinfolk, a loyal slave hid them in barrels and smuggled them to New Orleans. The slave, it turned out, was a voodoo queen.

But it wasn’t until Gandolfo reached adulthood that he learned that countless Creole families told versions of the same story. Still, he says, “I don’t think I even knew how to spell voodoo.”

That changed in 1972, when Gandolfo’s older brother Charles, an artist and hairdresser, wanted a more stable career. “So I said, ‘How about a voodoo museum?’” Gandolfo recalls. Charles—soon to be known as “Voodoo Charlie”—set about gathering a hodgepodge of artifacts of varying authenticity: horse jaw rattles, strings of garlic, statues of the Virgin Mary, yards of Mardi Gras beads, alligator heads, a clay “govi” jar for storing souls, and the wooden kneeling board allegedly used by the greatest voodoo queen of all: New Orleans’ own Marie Laveau.

Charlie presided over the museum in a straw hat and an alligator tooth necklace, carrying a staff carved as a snake. “At one point he made it known that he needed skulls, so people sold him skulls, no questions asked,” Gandolfo says. “Officially, they came from a medical school.”

Charlie busied himself with recreating raucous voodoo ceremonies on St. John’s Eve (June 23) and Halloween night, and sometimes, at private weddings, which typically were held inside the building and outside, in nearby Congo Square, and often involved snake dances and traditional, spirit-summoning drumming. Charlie “was responsible for the renaissance of voodoo in this city,” Gandolfo says. “He revitalized it from something you read in history books and brought it back to life again.” Meanwhile, Charlie’s more introverted brother researched the history of the religion, which spread from West Africa by means of slave ships. Eventually, Gandolfo learned how to spell voodoo—vudu, vodoun, vodou, vaudoux. It’s unclear how many New Orleanians practice voodoo today, but Gandolfo believes as much as 2 or 3 percent of the population, with the highest concentrations in the historically Creole Seventh Ward. The religion remains vibrant in Haiti.

Voodoo Charlie died of a heart attack in 2001, on Mardis Gras day: his memorial service, held in Congo Square, attracted hundreds of mourners, including voodoo queens in their trademark tignons, or head scarves. Gandolfo took over the museum from Charlie’s son in 2005. Then Hurricane Katrina hit and tourism ground to a halt: the museum, which charges between $5 and $7 admission, once welcomed some 120,000 visitors a year; now the number is closer to 12,000. Gandolfo, who is unmarried and has no children, is usually on hand to discuss voodoo history or to explain (in frighteningly precise terms) how to make a human “zombie” with poison extracted from a blowfish. (“Put it in the victim’s shoe, where it is absorbed through sweat glands, inducing a death-like catatonic state,” he says. Later, the person is fed an extract containing an antidote to it as well as powerful hallucinogens. Thus, the “zombie” appears to rise from the dead, stumbling around in a daze.)

“The museum is an entry point for people who are curious, who want to see what’s behind this stuff,” says Martha Ward, a University of New Orleans anthropologist who studies voodoo. “How do people think about voodoo? What objects do they use? Where do they come from? [The museum] is a very rich and deep place.”

The eighth graders—visiting from a rural Louisiana parish—filed through the rooms, sometimes pausing to consider candles flickering on the altars or to stare into the vacant eye sockets of skulls.

The braver girls hoisted Jolie Vert over their shoulders for pictures. (“My mom’s going to flip!”) Others scuttled for the door.

“Can we go now?” one student asked in a small voice.

By Abigail Tucker

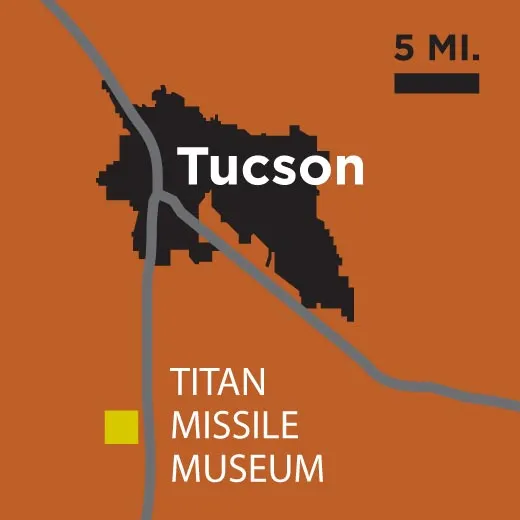

Titan Missile Museum

In 1963, the United States armed 54 missile silos with launchable nuclear bombs, which could travel some 6,000 miles each and kill millions of people, flash-blind hundreds of thousands and leave a blanket of nuclear fallout.

Beginning in 1982, as a result of a nuclear deterrent modernization program, the Defense Department destroyed the silos and mothballed the missiles. But one silo and its defanged missile near what would become a retirement community in southern Arizona called Green Valley, were preserved as a museum, a monument to the cold war. The Titan Missile Museum, 25 miles south of Tucson, celebrates its 25th anniversary this year.

Take a one-hour tour or opt for a $70 “top-to-bottom” inspection, in which eight underground floors can be thoroughly explored; many afford a frighteningly intimate look at the unarmed missile, still on its launchpad. It weighs 330,000 pounds and stands 103 feet tall. You can touch it.

Chuck Penson, the museum’s archivist and historian, recalls a tour he once gave to a former Soviet military commander familiar with the USSR’s missile defenses. “When he was on top of the silo looking down and heard the magnitude of power that could have been unleashed,” Penson says, “he put his head in his hand and meditated for a moment. It was clear that he found it a little upsetting.”

By Tom Miller

California Surf Museum

Oceanside, California

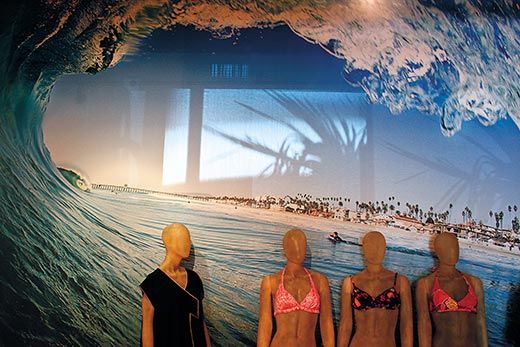

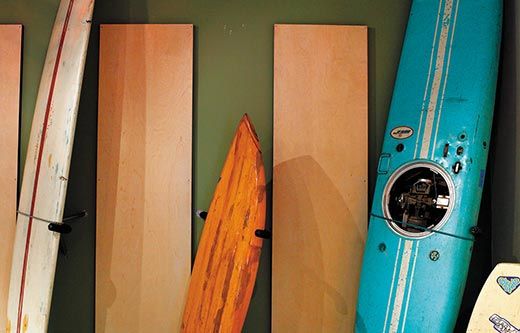

Started in a restaurant in 1986 in Encinitas, California, the California Surf Museum is finally—four locations later—in a space big enough to call home. The new address is courtesy of the city of Oceanside, about a 35-minute drive north of San Diego.

Leaning against a wall and hanging from the ceiling are 55 surfboards selected by curator Ric Riavic, a surfer and former school gardener, to show how surfboards have evolved. The oldest board, made of sugar pine in 1912, is seven feet long and weighs over 100 pounds. The newest, formed in 2008 and owned by four-time world champion surfer Lisa Anderson, is made of fiberglass, is nearly ten feet long and weighs around four pounds.

Duke Kahanamoku, the Olympic gold-medalist swimmer credited with being the father of modern surfing, owned a ten-foot-long, hand-carved board. “This is the type of board that started the surf craze in California in the early 1920s,” says Riavic. Kahanamoku often surfed at Corona del Mar, California, where he hung out with Johnny (“Tarzan”) Weismuller and John Wayne. Kahanamoku proved the perfect ambassador for the sport, and was photographed with everyone from Shirley Temple and Babe Ruth to the Queen Mother.

A 2008 photograph of an eight-foot wave curling up to Oceanside Pier by surfing photographer Myles McGuinness gives landlubbers an inkling of how it feels to be inside a surfing wave.

There are early surfing stickers and decals, record albums, vintage beachwear and photographs by 1950s surf photographer LeRoy Grannis.

“Surfing has captured so much of the culture’s imagination that people from all over the world want to connect to its spirit,” says the museum’s co-founder, Jane Schmauss. “I couldn’t imagine anything as beautiful as surfing not having a museum. It’s way cool.”

By Rodes Fishburne

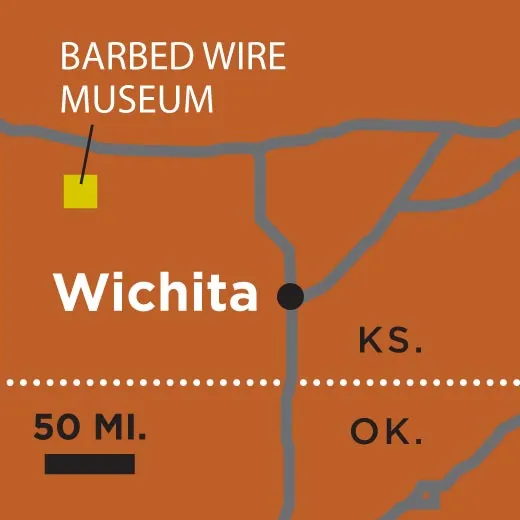

Kansas Barbed Wire Museum

La Crosse, Kansas

“Barbed wire was a lifesaver for this region,” says Brad Penka, president and curator of the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum, in La Crosse, Kansas. Let him count the ways: keeping animals, crops and vehicles apart and helping to make the treeless plains fencible and the United States a food exporter.

There are more than 2,400 variations of barbed wire. The first U.S. patent for a barbed fence attachment was issued in 1867. But it was not until 1874 that Joseph Farwell Glidden, a De Kalb, Illinois, farmer, patented a strand in which the barbs were held in place by twisted wire. Called “The Winner,” it would become the signature fencing of the American West.

By James M. Cornelius

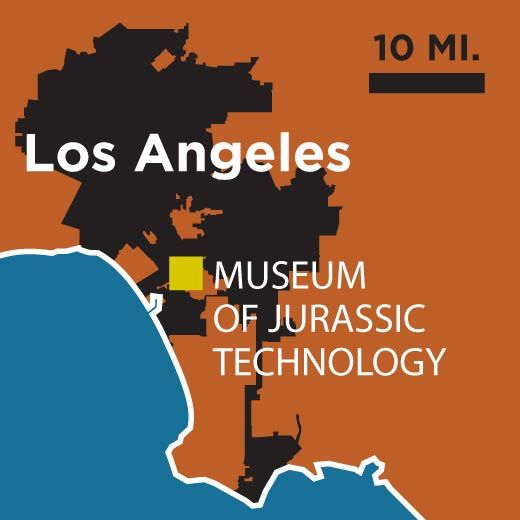

Museum of Jurassic Technology

Los Angeles, California

To find the Museum of Jurassic Technology, you navigate the sidewalks of Venice Boulevard in Los Angeles, ring a brass buzzer at a facade that evokes a Roman mausoleum and enter a dark, hushed antechamber filled with antique-looking display cases, trinkets and taxidermic animals. After making a suggested $5 “donation,” you are ushered into a maze of corridors containing softly lit exhibits. There are a European mole skeleton, “extinct French moths” and glittering gems, a study of the stink ant of Cameroon and a ghostly South American bat, complete with extended text by 19th-century scientists. The sounds of chirping crickets and cascading water follow your steps. Opera arias waft from one chamber. Telephone receivers at listening stations offer recorded narration about the exhibits. Wooden cabinets contain holograms that can be viewed through special prisms and other viewing devices, revealing, for example, robed figures at the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, or a man growling like an animal in front of a gray fox’s head.

The Jurassic Technology Museum is a witty, self-conscious homage to private museums of yore, such as the 16th-century Ashmolean at Oxford, where objects from science, nature and art were displayed for the “rational amusement” of scholars, and the 19th-century Philadelphia Museum, with its bird skeletons and mastodon bones. The phrase “Jurassic technology” is not meant literally. Instead, it evokes an era when natural history was only barely charted by science, and museums were closer to Renaissance cabinets of curiosity.

It is the brainchild of David Wilson, a 65-year-old Los Angeles native who studied science at Kalamazoo College, in Michigan, and filmmaking at the California Institute of the Arts, in Valencia. “I grew up loving museums,” says Wilson, whose scholarly demeanor gives him the air of a Victorian don. “My earliest memory is of just being ecstatic in them. When I was older, I tried making science films, but then it occurred to me that I really wanted to have a museum—not work for a museum, but have a museum.” In 1988, he leased a near-derelict building and began setting up exhibits with his wife, Diana Wilson. “We thought there wasn’t a prayer that we’d last here,” he recalls. “The place was supposed to be condemned!” But the museum slowly expanded to take up the whole building, which Wilson bought in 1999. Today, it attracts over 23,000 visitors a year from around the world.

Among the medical curios are ant eggs, thought in the Middle Ages to cure “love-sickness,” and duck’s breath captured in a test tube, once believed to cure thrush. Some exhibits have a Coney Island air, such as the microscopic sculptures of Napoleon and Pope John Paul II; each fits in the eye of a needle. Others are eerily beautiful. Stereo Floral Radiographs—X-rays of flowers showing their “deep anatomy”—can be viewed in 3-D with stereograph glasses to a clamorous arrangement by Estonian composer Arvo Part.

Near the exit, I read about a “theory of forgetting,” then turned a corner to find a glass panel that revealed a madeleine and a 19th-century tea cup; I pressed a brass button, and air puffed out of a brass tube, carrying with it (one was assured) the scent of the very pastry that launched Marcel Proust’s immortal meditation, Remembrance of Things Past. I wasn’t entirely sure what it all meant, but as I stepped out onto Venice Boulevard, I knew without a doubt that the world is indeed filled with marvels.

By Tony Perrottet

Ladew Topiary Gardens

Monkton, Maryland

The best place for watching the fox hunt at Harvey S. Ladew’s estate in Monkton, Maryland, is with the naked ladies. You stand among them under expansive trees, where the fox hunt never ends, regardless of season. That is because Ladew sculpted his life-size hunting scene—with fox, running hounds and mounted riders—out of living yew hedges.

Ladew, a socialite transplanted from Long Island, New York, lived hard, partied hard and planted exuberantly before he died in 1976 at age 89. Today, his antique-stuffed house and his topiary gardens attract over 30,000 visitors a year.

In one section of the gardens, one finds a statue of Adam and Eve: Adam accepts the forbidden fruit from Eve while hiding two apples behind his back. In another, Ladew has clipped a hedge into the shape of a fat man walking a tiny dog, his irreverent tribute to a Henry Moore sculpture.

“Mr. Ladew liked Henry Moore, but he didn’t have much use for modern art,” says Emily Wehr Emerick, executive director of the gardens. We’re in the Ladew house, where she pauses before a Picasso-inspired portrait of Ladew in hunting colors, with his nose on the side of his face where an ear should be. “It was a joke painted by his friend Elsa Voss,” says Emerick, who leads the way to Ladew’s oval library. She pulls a handle on one bookshelf, which swings open to reveal a secret entrance to the gardens—Ladew’s sanctuary when unwanted visitors appeared. “The housekeeper could honestly say he had stepped out for a moment,” says Emerick.

Near the garden’s entrance is a carpet of naked lady lilies that would soon burst into bloom. “[Ladew] had admired the lilies in a friend’s garden,” says chief gardener Tyler Diehl. “The friend cabled to say he would send 50 naked ladies to Monkton if Mr. Ladew could handle them. Mr. Ladew cabled back, saying that he could easily handle 50 naked ladies if they were disease free. Of course he knew the message would scandalize telegraph operators on both ends, which was part of the fun.”

By Robert M. Poole

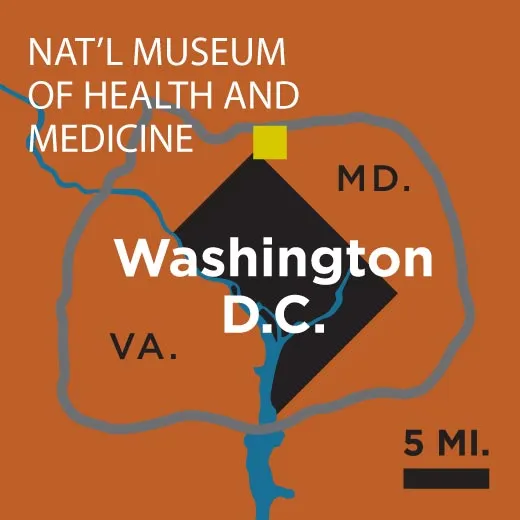

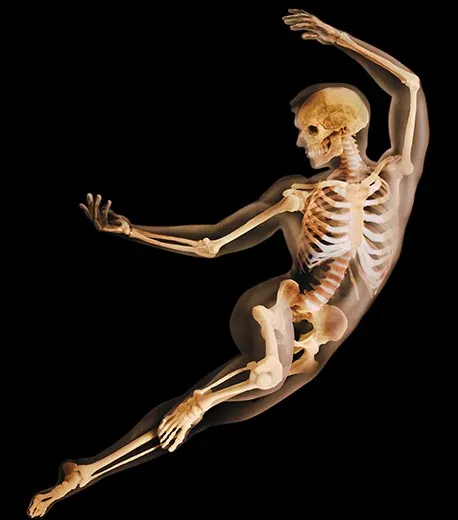

The National Museum of Health and Medicine

Victorian-era museums of medicine often seem like freak shows—corridors lined with displays of giant skeletons, deformed fetuses, amputated feet and cancerous lesions. But they were established with a noble purpose, as places where doctors-in-training could study actual specimens. The National Museum of Health and Medicine, in Washington D.C., which was created at the start of the Civil War to further the research of military field surgery and now is open to the public, is no exception. In 1862, Surgeon General William Hammond instructed Union doctors on the front lines to send him “specimens of morbid anatomy...together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed.” The Army Medical Museum (as the resulting collection became called) was staffed by doctors, and it quickly accumulated a wealth of grisly items for medical personnel to examine on their way to the front.

Today, staff members are no longer doctors and the exhibits relate to the history of military medicine, but there is still a vast archive of objects researchers can consult. The museum is currently housed within a wing of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, a facility that treats soldiers wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Near the entrance is a shattered human skull labeled “Effects of Canister Shot in the Civil War,” followed by more displays from that war: prosthetic eyes, a photograph of stacked amputated limbs. Close by are the leg bones of a certain Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, who donated his amputated limb to the museum and visited it regularly.

Perhaps the most famous items on display are from Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865; his autopsy was performed here. They include fragments of the slain president’s skull, pieces of hair, part of the doctor’s blood-stained shirt cuff, and reproductions of Lincoln’s face and hands—even the lead ball removed from his head, labeled simply “The Bullet That Took the President’s Life.”

One recent exhibit is almost as startling: “Trauma Bay II,” part of the actual field hospital used at the Army Air Force Base in Balad, Iraq, from 2004 to 2007. Although plaques explain that over 95 percent of soldiers treated there during that period survived, emergency military field surgery seems hardly less bloodcurdling than it did in the Civil War. The museum continues to be a place for education, only these days the subject is the ghastly toll of war.

The museum closed at its current location and will reopen in its new home, in Silver Spring, Maryland, this fall.

By Tony Perrottet