What If City Streetlights Brightened and Signs Spoke As You Passed?

A British designer has found a way to make urban areas work for all types of pedestrians

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/48/974871b5-f0a7-4e61-9cdd-12b632680729/respstreet1.jpg)

Ross Atkin spent a lot of time following people through the streets of London before he figured out how to make those streets more welcoming for people with physical impairments. He worked for the cities of York and Bath, and the UK government, to trace their movement, so planners could see how they interact with city infrastructure, and what gives them trouble.

Atkin is an engineer and designer who looks at how people with disabilities use public space. He’s helped cities evaluate their infrastructure to accommodate aging or handicapped populations, modeling how tactile pavement and roadwork barriers with raised dots on them could be used in various situations to direct those with sight loss.

The designer’s latest vision is to have pieces of street furniture in cities that can adapt in the moment to fit a pedestrian’s particular need. Responsive traffic signals could give the elderly more time to navigate crosswalks. People with mobility impairments often need places to sit down, so he has designed bollards, or short posts that line sidewalks, which convert into seats. He also wants streetlights to become brighter, and street signs to audibly give information about the buildings, businesses and services that are in front of them, to help the visually impaired.

The “responsive street furniture,” as Atkin calls it, could have other applications, too, with various populations standing to benefit. Maintenance workers could get alerts from full trashcans that needed emptying, and non-English speaking visitors could get directions in their own language from lampposts.

Most pieces of infrastructure today are designed based on averages—for instance, how long it takes someone to cross the street—or convenience—benches tend to be clustered in wider sections of sidewalk—and without much regard for how people on the tail end of the physical bell curve might move through those urban landscapes. It might just be a small sliver of the population who struggle with a lack of seating, or low lighting, but these design choices have a big impact on those people. Atkin talked to people who didn’t leave their homes alone, because navigating the city was intimidating.

“A dream of mine is that I can travel independently and feel safe wherever I’m traveling,” Steve Tyler, head of solutions, strategy and planning at the Royal National Institute for Blind People, who worked with Atkins, has said.

Atkin’s research turned up another point of frustration—the fact that most accessibility measures are focused on single disabilities.

“I realized that loads of the design decisions were tradeoffs between impairments groups,” he says. For instance, ramps, which are necessary for people in wheelchairs or other rolling devices, can be hazardous for people with vision impairments, who use curbs to navigate.

A year and a half ago, Atkin decided he wanted to turn his research into something actionable. In addition to urban planning, the Nottingham University-educated engineer is also interested in the Internet of things, the idea that inanimate objects will be able to digitally communicate with each other. He figured he could combine the two, and use digital connections to trigger parts of the urban landscape to respond to individuals.

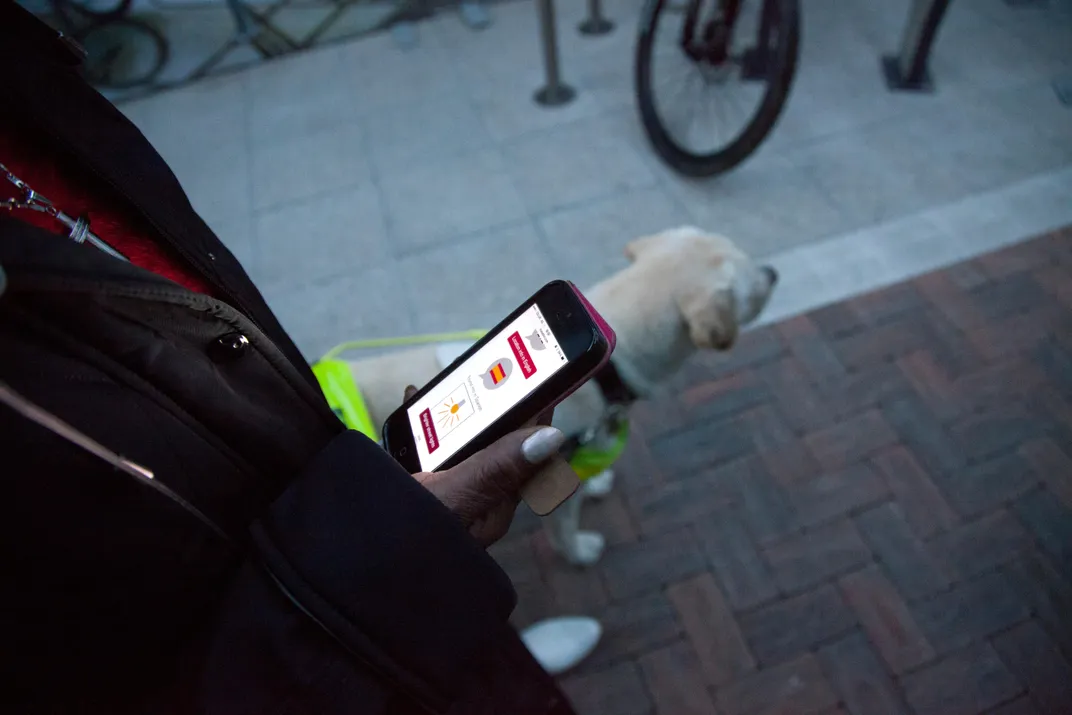

Users would log into an app and check off the kinds of assistance they require. A sensor in their phone, key fob or fitness tracker would then signal to the lights or bollards that they were coming, and the structures would respond to their specific needs. People who don’t need a place to sit down won’t have to deal with benches taking up sidewalk space, because they’ll slide back into the bollards when they’re not in use. And, instead of having a walk light that pings loudly all the time, it’ll only make noise when someone with a visual impairment is nearby, making it less intrusive on the neighborhood.

Atkin, who worked with landscaping manufacturer Marshalls to develop the system, says the technology is ready to go and relatively easy to implement. The challenge is getting cities to change their infrastructure—whether that be adding bollards or adjusting traffic flow, which can incur costs that aren’t built into municipal budgets.

Some of the changes, like the variable traffic crossings, are particularly tricky, because they have cascading effects on the flow of traffic. Those crossings will likely have the biggest impact, but some of the smaller pieces, such as the bollards that turn into benches, are being implemented first. “It’s to do with what we can easily get our fingers into,” he says. “Technically connecting these things up is pretty easy.”

Atkin has been working on this project for a year and a half. He prototyped the bollards last March, at a Landscape Institute event, to see how they functioned in the wild and to dial in the range of the sensors, then developed final versions in October. The first ones have been installed in the Bloomsbury neighborhood of London as part of an exhibition put on by New London Architecture. It’s called “Never Mind the Bollards,” a Sex Pistols reference, which might imply that punk fans are getting older.

“There’s a lot of talk currently about smart cities, age-friendly communities and intelligent street furniture to help older and disabled people get around,” says Jeremy Myerson, a professor at the Royal College of Art in London. “This project is a real, practical manifestation of this thinking.”

The London Design Museum selected Atkin’s responsive street furniture as one of its Designs of the Year for 2015, after Myserson nominated the project for the award. The bollards, light posts and traffic crossings are on display there until August 23, for visitors, even the able-bodied, to try out.

Now, the system just needs to be stress-tested in the real world.

“Everyone seems quite excited about it, the challenge is figuring out who is actually going to implement it,” Atkin says. “Even if we only have one crossing connected, it can impact a lot of people in the area.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0196_2.JPG)