This Dutch Wind Wheel Is Part Green Tech Showcase, Part Architectural Attraction

A giant structure proposed in Rotterdam puts cutting-edge energy tech inside a rotating observation wheel, with room for a hotel and apartments

The Dutch have a long history of harnessing wind power. As far back as the 13th century, residents used windmills to pump water out of marshlands and lakes to create useable farmland. Along the way, the windmill became an icon of the country, along with the tulip fields that the wind-powered pumps made possible.

Now, a group of Rotterdam-based companies wants to update the windmill for the the 21st century, while drawing millions of tourists to the Netherlands’ second-largest city and kick starting a local green-energy economy in the process.

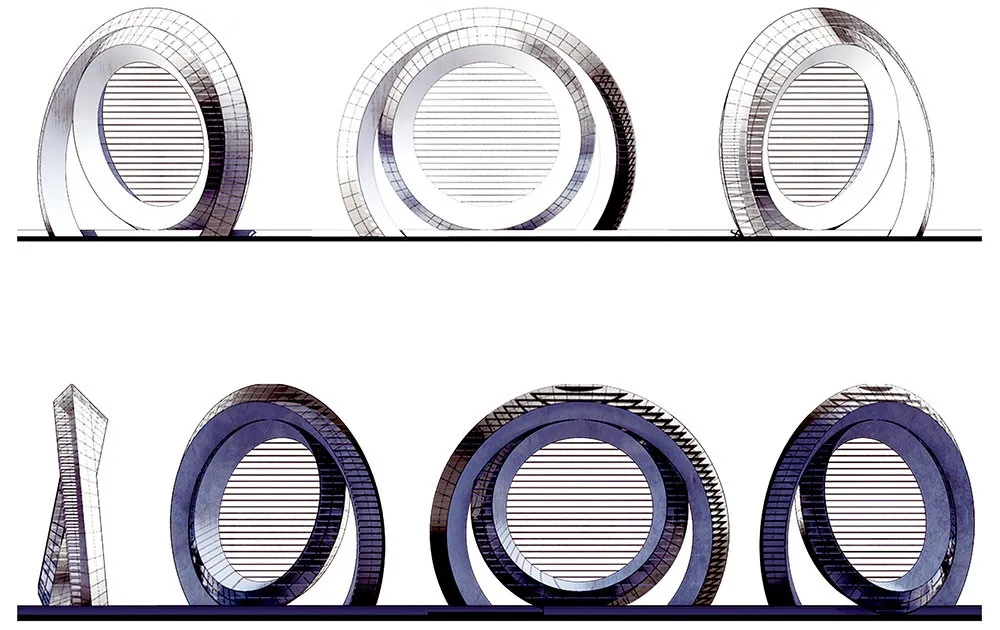

The group’s proposed Dutch Wind Wheel is an ambitious, 570-foot-tall structure that would harness the wind to generate electricity, without the noise-polluting, mechanical moving parts of traditional wind turbines, which previous studies have shown kill hundreds of thousands of birds a year.

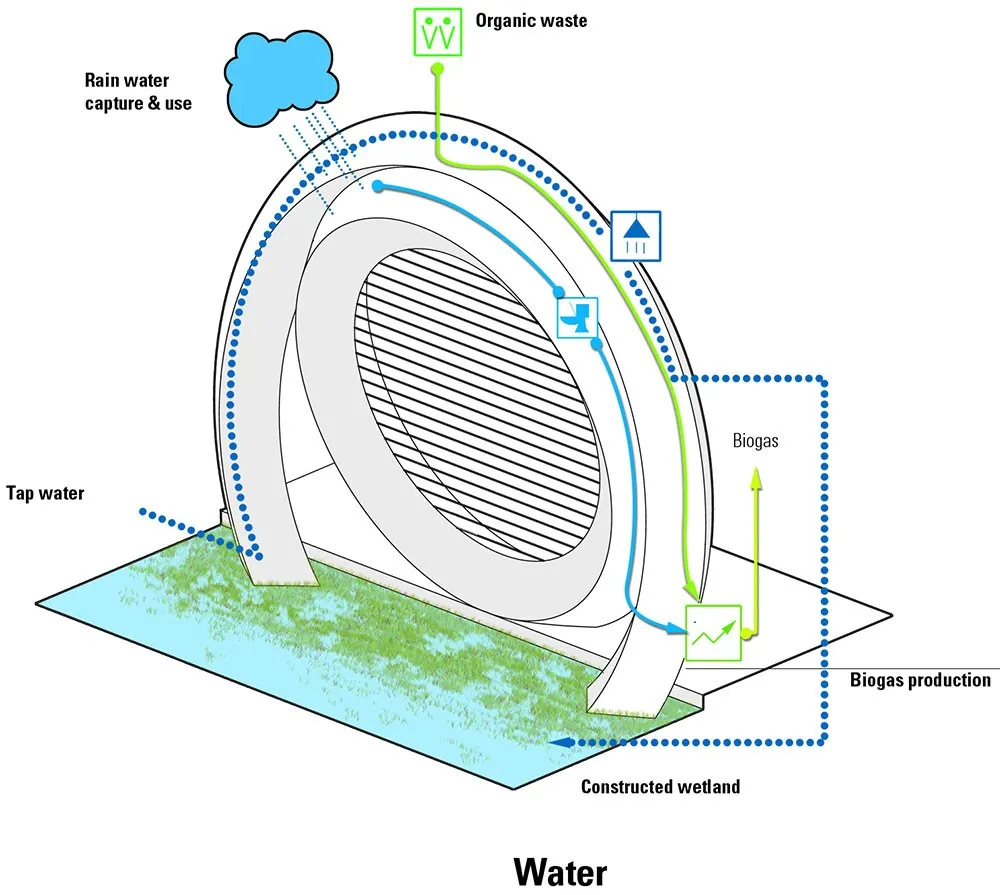

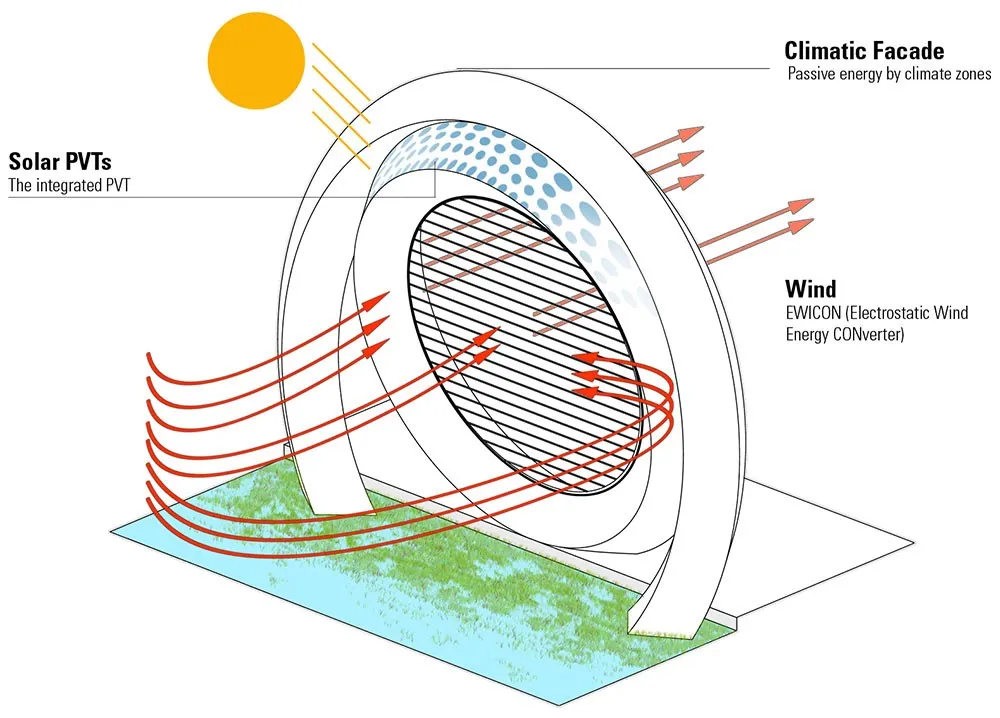

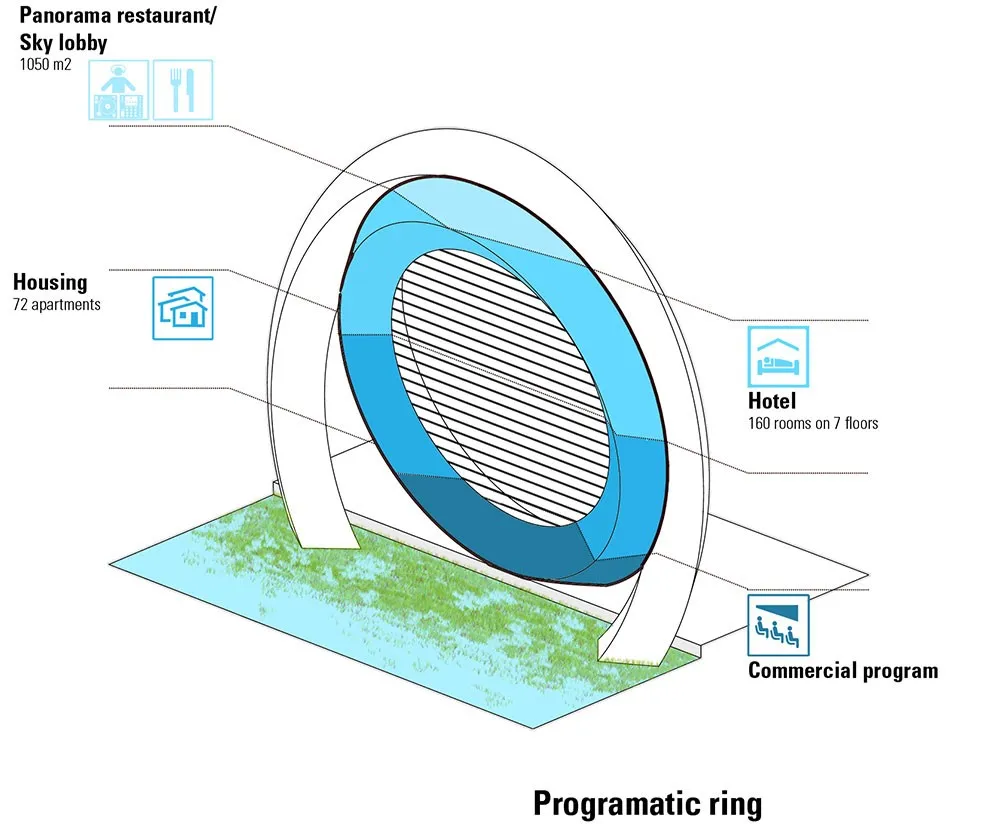

The Wind Wheel’s design, made of two massive rings and an underwater foundation, plans to incorporate other green technologies, including solar panels, rainwater capture and biogas creation. The biogas will be created from the collected waste of residents of the 72 apartments and 160 hotel rooms that are planned for the inner ring.

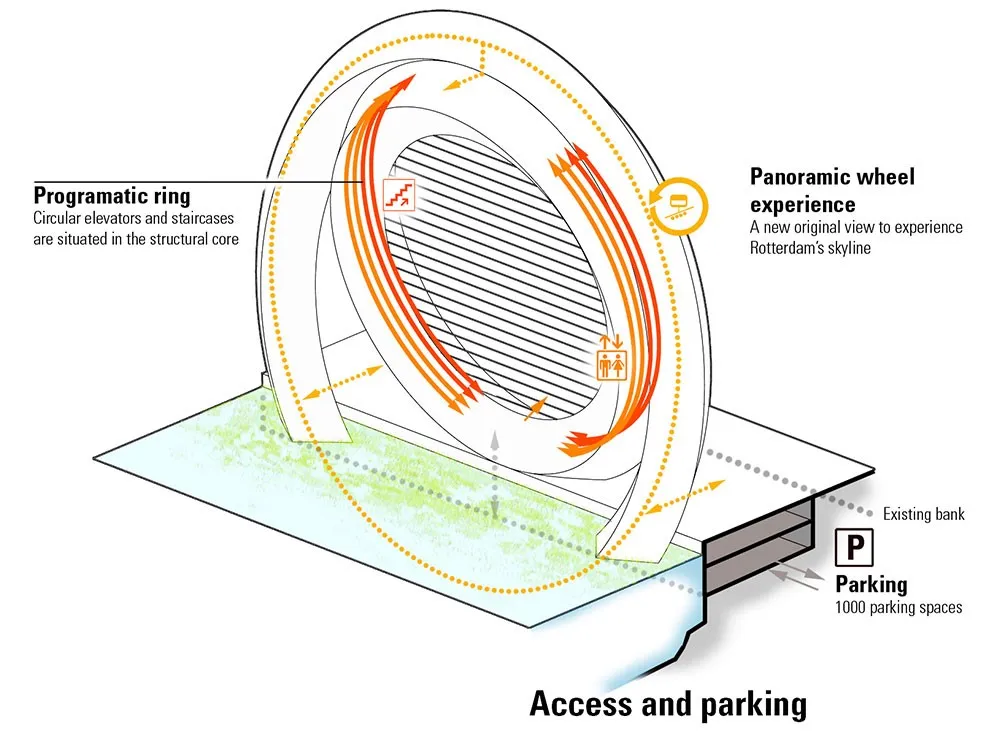

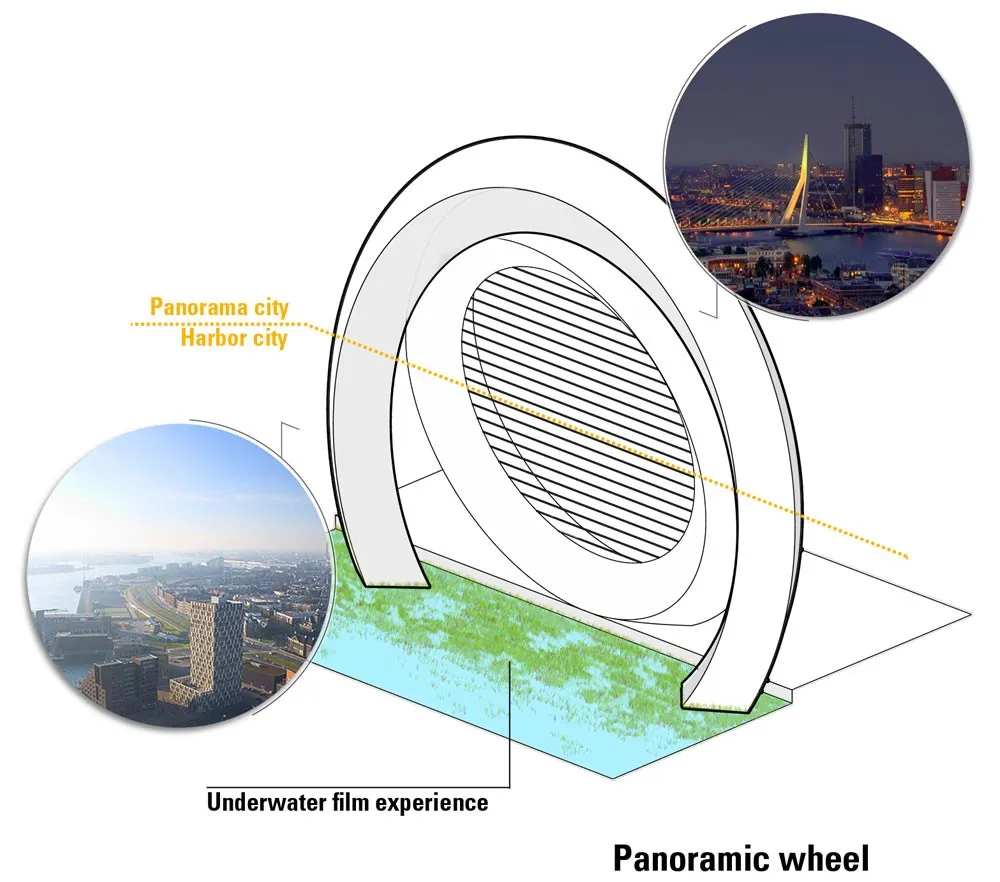

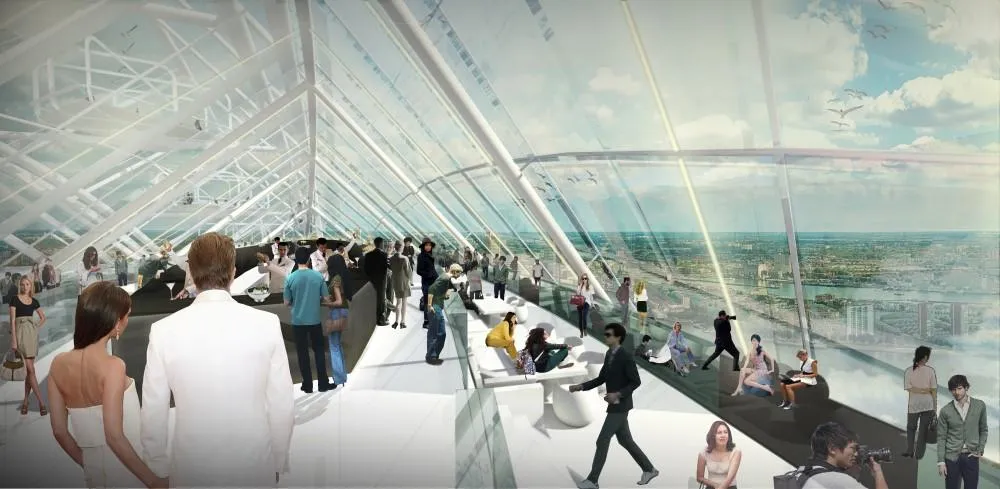

The outer ring is set to house 40 cabins that move along a rail like a roller coaster, giving tourists a view of the city and the surrounding countryside, much like the London Eye or Las Vegas’ High Roller, which became the world’s tallest observation wheel when it opened in 2014. The cabins have glass "smart walls" that project information—the current weather, for example, and the heights and architects of buildings—onto the panorama. A restaurant and shops are also planned within the proposed structure.

While aspects of the Wind Wheel’s design seem futuristic, the technology will have several years to advance before final construction gets underway. Duzan Doepel, the project’s principal architect, says that the Wind Wheel is still in its beginning phases.

“The concept is defined, and we’re at the beginning of a two-year R&D trajectory,” says Doepel. “We’re talking to the ministries of economic affairs and local authorities, who are interested in helping us develop this concept.” He says if they prove that the wheel’s bladeless turbine tech can be scaled up for use in the Wind Wheel, the building may be finished by 2025.

But that’s a substantial if. The turbine technology, dubbed EWICON (Electrostatic WInd Energy CONvertor) was initially developed in 2013 at Delft University of Technology, just 10 miles north of Rotterdam. It uses a series of tubes, to be strung along the Wind Wheel’s inner circle, that creates an electric field into which positively charged water drops are sprayed. Wind blowing through the wheel pushes the water away from negative electrodes in the tubes, creating resistance that can be harnessed as energy.

While the concept has been proven effective in small prototype form, it has yet to be tested on a scale approaching the size of the proposed Wind Wheel. And a message at the top of Delft’s page on the subject notes rather ominously “…there is no evidence that this principle is suitable for use on a commercial scale. At present TU Delft is not actively involved in the further development of the EWICON.”

Doepel says that the professor, Johan Smit, and the PhD graduate, Dhiradi Djairam, who developed the technology at Delft University are still working on it outside of the university. The Wind Wheel group is hoping collaboration with the inventors and commercial interests will lead to further breakthroughs in the next two years and allow the technology to function effectively on a large scale. But at the moment, they aren't publicly speculating about how much energy the final structure might generate.

“Part of the research and development will be the implementation of smaller prototypes,” says Doepel. “We don’t imagine we’ll go from laboratory to this scale in one step.” He says the group is working with local authorities to find possible locations for smaller pilot programs. “If we do manage to do it at this scale,” says Doepel, “it will be the biggest windmill in the world—at least as far as we know.”

Aside from being a showcase for sustainable technologies and a tourist attraction, the group hopes the Wind Wheel will help grow the area’s so-called Clean Tech Delta, which aims to “be an international business zone for clean tech companies that opt for the region of Rotterdam–Delft as their Gateway to Europe.” That would of course also mean more jobs, which the country sorely needs. According to a 2014 government report, Rotterdam had the highest unemployment rate of the four major Dutch cities—14 percent at the time of the study.

Doepel also points out that aside from its green tech ambitions, Rotterdam is also a good location for the Wind Wheel because the city has a tradition in modern architecture, with several distinctive structures. But the Netherlands isn’t the only place the Wind Wheel could land.

“Rotterdam is the best location to put this primary structure down,” says Doepel. “And obviously, the concept can be exported as well. So if we do manage to build this in the Netherlands as our first prototype, I would expect China to be the next place.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)