Tactical Urbanists Are Improving Cities, One Rogue Fix at a Time

And city governments are paying attention, turning homemade infrastructure changes into permanent solutions

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5e/95/5e95f1dc-ca8f-4163-8eb5-ad12a7f1a223/328490_217333425022356_1714610624_o.jpg)

One rainy January night in Raleigh, North Carolina, Matt Tomasulo went out to commit what some would call vandalism. Along with his girlfriend and a friend, the graduate student walked around downtown hanging homemade signs on lampposts and telephone poles. The signs featured arrows pointing the way to popular downtown destinations, along with average walking times. Tomasulo called the project “guerrilla wayfinding.” His decidedly un-criminal intent was to promote more walking among Raleigh citizens.

Frustrated by the syrup-slow pace and red tape of the traditional civic change process, citizens across the country are bypassing the bureaucratic machine entirely and undertaking quick, low-cost city improvements without government sanction. They’re creating pop-up parks in abandoned lots. They’re installing free library boxes on street corners. They’re creating homemade traffic-slowing devices using temporary obstacles like potted plants to make their streets safer.

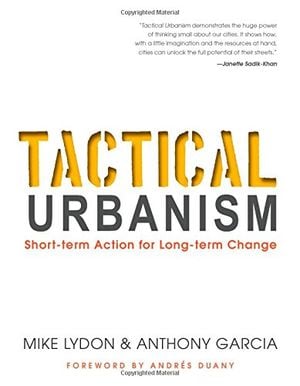

New York-based urban planner Mike Lydon coined the term “tactical urbanism” several years ago to describe the phenomenon. Now, Lydon and fellow planner Anthony Garcia have come out with a new book, Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change, offering a history of the movement and a guide for aspiring practitioners.

“There are so many new types of public demands, and cities have a hard time responding in a way that’s nimble,” Lydon, 33, says. “I see a lot of people who are just frustrated with the decades of accumulated policies.”

The DIY civic-mindedness of tactical urbanism is generally aimed at making cities friendlier, more community-oriented and more walkable. In San Francisco, activists turned parking spots into “parklets” complete with AstroTurf and café tables, making a car-centric landscape more pedestrian friendly. In Memphis, advocates for downtown revitalization transformed a long-abandoned historic brewery into a temporary beer garden. In Baltimore, a concerned citizen painted a crosswalk on a busy street when the city failed to do so. And a band of volunteers in Toronto have placed more than 400 brightly colored ramps in front of business entrances to make them wheelchair accessible.

The rise of tactical urbanism is due to a convergence of several factors, Lydon says. Over the past five to seven years, more and more young people—especially the relatively affluent and educated—have moved to cities. The number of college-educated adults between 25 and 34 living within three miles of a city center has grown 37 percent since 2000. These young urbanites want real “city living,” with walkability and vibrant street life. At the same time, the Great Recession has meant cities have had even less money for civic improvements. From 2010 to 2012, just as tactical urbanism was heating up, 25 percent of American cities reported cuts to services like parks and recreation, libraries and public works, while nearly half laid off municipal workers. Frustrated, citizens began to take matters into their own hands. This kind of consumer-driven innovation resonates particularly with Millennials.

“We’re so used to having the new version of the phone and the app and the software program, we kind of expect versioning in life, including in the city,” Lydon says.

Thanks to the internet, a successful tactical urbanism project can be quickly replicated in other cities. In Portland, an initiative to beautify neighborhood intersections with murals and community bulletin boards has inspired similar projects across the United States and Canada. San Francisco’s parklets have gone global with an “open source” how-to manual available online. Now, so-called “PARK(ing) Day” is held each September in hundreds of cities on six continents, with artists and ordinary citizens transforming parking spots into mini parks.

In the best cases, tactical urbanism’s homemade fixes lead to long-term solutions. Tomasulo’s guerrilla wayfinding signs eventually encouraged the city of Raleigh to adopt a new pedestrian plan, one which used signs like his. In Memphis, the beer garden was such a hit it attracted a developer who plans to turn the old brewery into mixed-use commercial and residential space. And Baltimore officials caught wind of the rogue pedestrian path and added two stop signs and three official crosswalks.

Tactical urbanism is not anti-government, Lydon says. It can in fact be a powerful tool for municipalities. Instead of creating huge, costly 20-year master plans for civic improvements, cities can try a piece-by-piece “see what works” approach, incorporating public feedback. New York’s temporary installation of 376 lawn chairs in Times Square in 2009 was an example of government-driven tactical urbanism. The project was so successful the city decided to make a permanent pedestrian zone with seating between Broadway and 7th Avenue and 42nd and 47th Streets.

As the world continues to urbanize—according to United Nations projections, 66 percent of all people will live in cities by 2050—cities will need to respond more rapidly and fluidly to evolving needs.

“As cities change, their approaches can change,” Lydon says. “Tactical urbanism isn’t a silver bullet for everything, but it’s a great tool.”

Lydon and Garcia urge aspiring tactical urbanists to think small. “Opportunities to apply tactical urbanism are everywhere,” they write. A vacant lot, a decrepit warehouse, a too-wide street: these are all potential project sites.

But don’t go hauling off with a can of paint and a roll of reflective tape without some planning, the two advise. Tactical urbanism is above all about community. Ask yourself if your project targets a true community need. Involve other people. Consult local government, if feasible. Make a budget.

“[W]e can’t guarantee that your $2,000 project will catalyze $2 million of municipal or private investment,” Lydon and Garcia write. “…but we can promise that these things will never happen unless someone takes action.”