Shell Fame

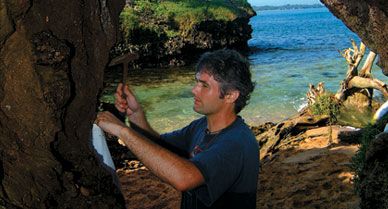

Paleobiologist Aaron O’Dea has made his name by sweating the small stuff

For 100 million years, North America and South America were islands unto themselves, separated by a sea that linked today's Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Then, over the course of a mere million years—about a week and a half in people years—everything changed. The continents pushed together at what is now Panama and isolated the Caribbean Sea. The Pacific remained cold, muddy and full of nutrients, but the Caribbean became relatively barren—currents that once brought food toward the surface were blocked by the Isthmus of Panama, and the water turned warm and clear (conditions that are great for scuba diving but not so great for clams and other mollusks).

Above sea level, meanwhile, opossums, armadillos and ground sloths crossed the new land bridge, which filled in about 3.5 million years ago, from south to north; squirrels, rabbits and saber-toothed cats scattered from north to south.

All this upheaval makes Panama "an amazing place for paleontology, a place that makes people realize the world was different," says Aaron O'Dea. He came to Panama five years ago and ended up studying underwater extinctions. What he discovered came as a revelation: even though the environment in the Caribbean changed as soon as the Isthmus of Panama rose out of the sea, no mass extinction took place until two million years later.

What does this unexpected delay between cause and effect mean for paleontology? Well, it complicates things. Only rarely is there a smoking gun for a mass extinction—evidence that an asteroid slammed into the Yucatán and killed off the dinosaurs, say. Now we know of a gun that might have fired millions of years earlier, O'Dea says, which means "what we should be doing is looking more carefully at the ecological changes behind big extinctions."

That's what he has done in Panama, sifting through 30 tons of sediment in 3,000 bags from more than 200 sites, cataloging every shell or skeleton fragment larger than one-twelfth of an inch. Such thoroughness has allowed him to determine that mud-loving mollusks hung on in the Caribbean for millions of years after people assumed they had disappeared.

O'Dea, 35, has been hunting for fossils since he was a kid. He and his mother, a nurse, lived on a succession of communal farms in England. The other children on the communes were like brothers and sisters to him. He got adults to take him to quarries, and he dreamed of collecting dinosaurs. But by the time he got to college, at the University of Liverpool, "I'd realized dinosaurs were a little overrated."

In fact, he thinks most glamorous specimens are overrated. The problem, he says, is that scientists used to "collect nice shells, or bones and teeth and put them in museums" where they could be studied. But museum-quality material "is not representative of what existed in the past."

More representative—and informative—are the lowly Bryozoa, for instance, communal animals sort of like corals. O'Dea can tell how warm the water was millions of years ago by looking at the size of fossilized bryozoan shells. The walls of his lab at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Balboa, Panama, are hung with close-ups of pinkie-nail-size Bryozoa colonies, lacy and delicate like snowflakes.

O'Dea is an accomplished photographer, and not just of fossilized sea creatures. He's now putting together a show of "People of Panama" for a January exhibition at the French embassy there. Last year his "Portraits of an Isthmus" photographs toured Spanish embassies around the world.

He's found a way to make both art and science part of his life, but for a while it looked as though science would lose out. After completing his PhD at the University of Bristol, he went to Panama for a short fellowship and worked with marine ecologist Jeremy Jackson of STRI and the University of California at San Diego. O'Dea got so sick from amoebic dysentery that he had to be hospitalized, and he was nearly killed by a falling coconut. "I went back to England and said I refused to ever set foot in that disgusting country again in my life," O'Dea says. He became a sculptor, working in slate and marble. After about a year and a half, Jackson wrote to him, O'Dea recalls, to say " 'Come on! Pull yourself together, and get yourself out of that hole!'" O'Dea came back to Panama, and this time it took.

Now, when he's not out photographing people on the streets (standing well clear of coconut trees), he's focusing again on Bryozoa. Did sexually or asexually reproducing lineages (Bryozoa come in both flavors) adapt better to the changing environment in the Caribbean? So far it looks like Bryozoa will score another point for sexual reproduction. In Panama, says O'Dea, "you can answer questions like this."

Laura Helmuth is a senior editor at Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/laura-helmuth-240.jpg)