The Pharmacist Who Launched America’s Modern Candy Industry

Oliver Chase invented a lozenge-cutting machine that led to Necco wafers, Sweethearts and the mechanization of candy making

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/f3/f4f35493-3010-4f49-bc73-9bec4f244d61/sweethearts_candy.jpg)

With their chalky-sweet taste and corny messages (“Be Mine,” “Dream Big”), Sweethearts, that middle school Valentine’s Day staple, hardly seem innovative. But a century and a half ago, the tiny sugar paste hearts were downright cutting edge. They were produced on one of the first candy machines to be invented in the United States, a machine that changed the course of American candy history.

By the mid-19th century, sugar, once expensive, had become plentiful and cheap, largely due to slave labor on sugar plantations, which supplied a growing number of American sugar refineries. But candies were still produced much the way they’d always been. Confectioners stirred heavy copper pots over open flames to make hard candies or caramels. Comfits—nuts or seeds with candy shells (think Jordan almonds)—had to be “panned,” which involves repeatedly rolling ingredients in hot sugar over several days.

“If you wanted to have a business making candy early on, it was not only expensive, it was really difficult, hot, sweaty work,” says Beth Kimmerle, a culinarian and the author of several books on America's confectionary history.

Enter Oliver Chase, an English-born pharmacist who’d recently immigrated to Boston. Chase made apothecary lozenges, rolling ropes of sugar-and-gum dough mixed with medicinal ingredients and cutting them into tablets. There were some rudimentary cutting machines to speed up the process, but it was still slow and painstaking. And demand for lozenges was high, especially when Chase started making versions without medicine, which could simply be eaten as candy.

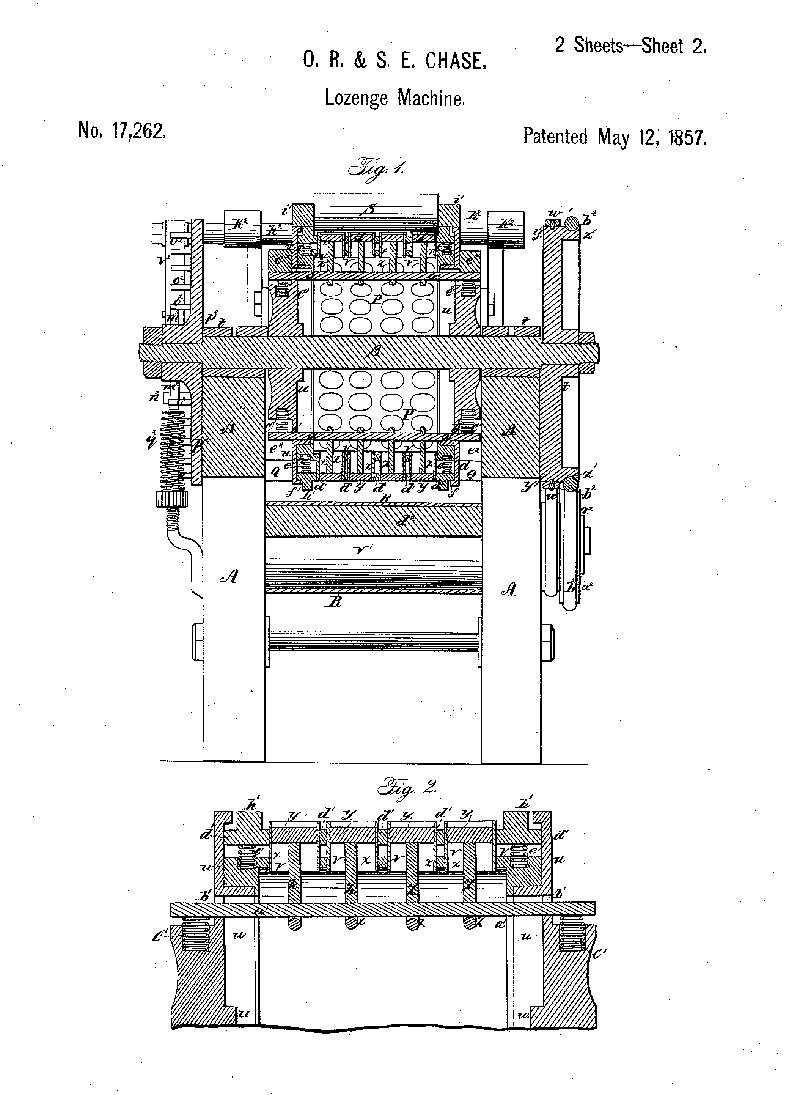

In 1847, Chase came up with a solution: a lozenge-cutting machine. Resembling a hand-cranked pasta maker, his invention stamped sheets of sugar dough into circular lozenges. Dozens of identically sized lozenges would come tumbling out all at once. Chase and his brother set up a factory in South Boston producing “Chase lozenges.” Their company would later be known as the New England Confectionary Company (Necco), which would go on to become America’s longest-operating candy company. The lozenges, with flavors like clove and cinnamon, were a hit.

Chase didn’t stop innovating there. He improved and expanded his lozenge machine many times. In 1850, he invented and patented a machine for pulverizing sugar. Then, in 1857, he patented an iteration of his lozenge machine. (While many sources talk of an 1847 patent of the lozenge-cutting machine, an extensive search of the patents of this time period in this technology could not confirm this allegation.) Soon, Chase and his brother Daniel got the idea to print words on their lozenges. They were inspired by a popular 19th century candy called "cockles," which were shell-shaped sugar wafers with paper sayings tucked inside, fortune cookie-style. At first the brothers printed the sayings by hand. Since the lozenges were fairly large, they could accommodate long statements (Victorian favorites included “How long shall I have to wait? Pray be considerate” and “Please send a lock of your hair by return mail”). Then, in 1866, Daniel Chase invented a lozenge printing machine, which used a felt roller pad moistened with vegetable dye to print directly onto lozenges. That sped up production considerably, and in 1902, the company began producing printed heart-shaped lozenges. Sweethearts were born.

While the Chase brothers were certainly clever and enterprising, their inventions were possible because of their environment, Kimmerle explains. Massachusetts was a center of the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, and the idea of mechanization was on everyone’s minds. The state also had a rich agricultural tradition and a busy port, making raw ingredients easy to access. Necco was quickly joined by other candy companies, including Squirrel Brand, famous for its nutty Squirrel Nut Zippers taffy, and the Daggett Chocolate Company. A stretch of Main Street in Cambridge had so many candy factories it became known as Confectioner's Row. By the late 1800s, candy was to Boston what computers were to Silicon Valley a century later.

Oliver and Daniel Chase's inventions revolutionized the candy industry. By the Philadelphia Exposition of 1876, nearly two dozen candy companies showed off products made with industrial machinery. Candy was no longer an artisan product, but an industrial one.

For years, Necco products were American favorites, sold in every corner store and shipped to soldiers overseas—in both world wars, the U.S. government requisitioned the company’s iconic Necco Wafers for army rations, since the candies didn’t melt and were shelf-stable for years. Explorer Admiral Richard Byrd took 2.5 tons of Necco Wafers on his 1930 Antarctic expedition—a pound a week for each man for 2 years.

But times change, and what was once innovative eventually becomes old-fashioned. Necco went out of business last July after more than 170 years. These days the Boston area is a hub for biotech, not candy, and Necco's Cambridge factory is now home to global research operations for the pharmaceutical giant Novartis. The company spent some $175 million converting the building, which involved scraping sugar from the walls.

“Times have changed, and a lot of candy companies that sort of rested on their older manufacturing ways can’t compete with the ones that are highly mechanized,” Kimmerle says.

Fortunately, Sweethearts have survived their maker’s demise. When Necco went under, the brand was sold to the Spangler Candy Company. Unfortunately, Spangler hasn't had time to ramp up production, so there will be no Sweethearts this Valentine’s Day. But don’t worry, the little heart-shaped pieces of American candy history should be on shelves again before next February.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)