Insect Farming Kit Lets You Raise Edible Bugs

The Tiny Farms setup comes with everything to cultivate one of the world’s most sustainable (and popular) sources of food

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/db/e8/dbe857d3-7b14-4b28-a3a6-102059433e17/763442692.jpg)

In the west, we have a cultural distaste for most bugs. We're the land of pesticides, systematically going to great lengths to avoid or get rid of them. Even the word "bug" in everyday vernacular has evolved to connote unsavory behavior.

But to the chagrin of the most aversive entomophobes, much of the scientific literature has found that as many as 1,7000 species are not only safe to eat, they're also nutritiously more beneficial than much of the food we normally consume. Compared to beef, "a six-ounce serving of crickets has 60 percent less saturated fat and twice as much vitamin B-12 than the same amount of ground beef," according to a PBS NewsHour report. Besides being a good source of lean protein, bugs are genetically distant enough from us that transferable diseases such as mad cow or feral pig disease won't ever be a concern. There's a reason why, for 80 percent of the world’s nations, insects are actually an essential part of people's diets.

Yet, to satiate the culinary preferences of the few, an agricultural system has been set up that devotes over two-thirds of the world's farmland to raising livestock, while ultimately yielding only half an ounce of cooked beef for every pound of feedlot grain. The sheer amount of grain that goes into producing meat in the United States alone each year is enough to feed nearly 800 million people during that time. Meat production is also responsible for 20 percent of all the greenhouse gases, according to a report in the Guardian.

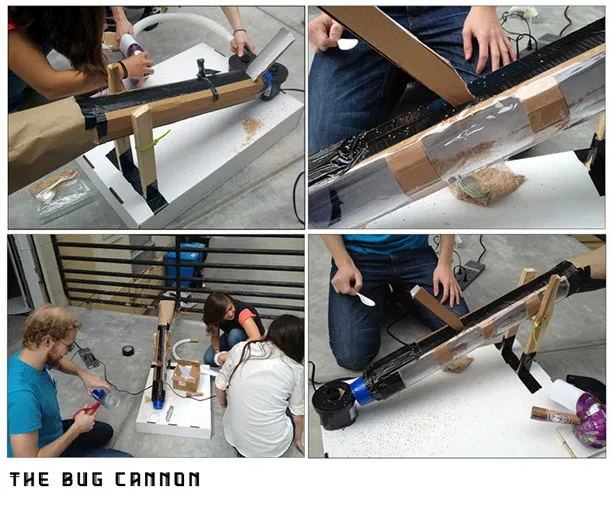

For San Francisco-based software engineer Daniel Imrie-Situnayake, this approach to food production for a rapidly growing population isn't only inefficient, it's simply unsustainable. His response was to develop, along with a team of entomological experts, a DIY open-source bug farming kit that he hopes to make commercially available in the near future, possibly as early as the beginning of 2014.

Each Tiny Farms kit comes with all the necessary equipment, including a bug starter pack, to hatch and cultivate your choice of insect. With an instruction guide, tutorials as well as software to track, manage and interact with a community of bug farmers, novices will be guided through all aspects of the process. Though a purchase price for the kit hasn't been determined, the company promises the materials will be low cost and readily available worldwide.

The concept was designed for enthusiasts to take advantage of the fact that though the world is already crawling with these potentially edible critters, only a few large-scale, food-grade insect producers exist. Assurances of food-grade sanitation matters because wild insects may be contaminated with pesticides, metals and other chemicals. With the enclosed kits, owners can rear herds for personal consumption (silkworm pancakes, anyone?), to feed other animals or to sell them on the market for as much as $15 per 1,000 crickets.

"The bottleneck now is supply," Imrie-Situnayak writes on Xconomy. "With only a couple of food-grade insect farms like World Ento and Chirp, the industry’s total production capacity is relatively small. At this moment, any entrepreneur with the resources to start a cricket farm has a guaranteed market for their produce."

As cold-blooded invertebrates, insects generally don't expend energy to keep warm and thus require less natural resources to thrive. For instance, they use their exoskeletons to seal in and preserve water when it's hot rather than sweating the way mammals do. The United Nations, in encouraging insect consumption, points out that insects, such as crickets, require six times less feed than cattle, four times less than sheep and two times less than pigs to reap the same amount of protein. On the whole, they're much easier to raise.

“Insect rearing can be very simple and low-tech. Also, unlike grazing mammals, they don’t need large horizontal areas to live in, and they can be stacked in a vertical environment for maximum efficiency of limited space,” Phil Torres, a conservation biologist at Cornell University, tells Modern Farmer. “Many insects certainly do adapt well to farm-like environments. Numerous species can be raised in high densities, especially compared to mammals, so you can get a much higher nutritional output per unit area used to raise them.”

Besides Tiny Farms, a growing number of eco-conscious bugstock advocates are exploring various tacts to help change people's perceptions of insects as food. In Spain, bug farmer Laetitia Giroud raises crickets to be milled into an unrecognizable fine powder that can be used as an ingredient in desserts such as cookies. And in Montreal, a team of students from McGill Univeristy has been awarded the 2013 Hult Prize ($1 million) to start grasshopper farms in developing regions in Mexico, Thailand and Kenya. The resulting yields would then be grounded and turned into flour for bread and other baked goods.

Tom Turpin, an entomologist at Purdue University and fellow insectivore, argues however that the only way for insect farming to reverse some of the environmental strain brought about by meat production is to scale it up to a similarly massive level. "It doesn't mean we couldn't do it," he tells Business Insider. "But we haven't spent the time culturing insects in the way we have cultured plants and animals for that food purpose."

But for now, perhaps the biggest hump continues to be that much of the world's food-producing systems and the communities built around them also depends on the eradication of bugs, rather than the harvesting of them. While agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development and British Locust Control are geared toward preserving important crops such as wheat and barley, there's a certain misguided irony in such efforts to wipe out swarms of insects that are essentially complete proteins in order to protect an incomplete one.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tuan-nguyen.jpg)