How Politics Has Changed Modern-Day Sports

Sportswriter Dave Zirin counts the ways that political issues have infiltrated sports at every level

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/big-idea-sports-politics-631.jpg)

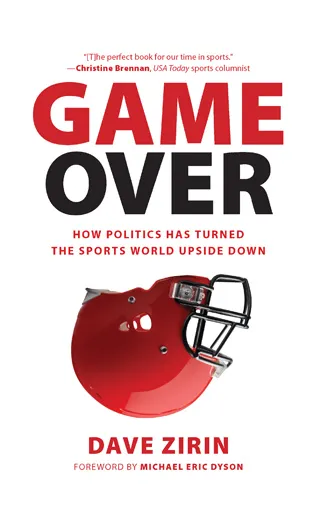

What do civil rights have to do with pro football players? What does the economic recession have to do with the Olympics? Everything, says Dave Zirin, author of the new book Game Over: How Politics Has Turned the Sports World Upside Down. The first sports editor in the history of The Nation, Zirin has spent over a decade writing about the intersection of sports and politics. He argues that political and social issues have permeated sports at all levels, from youth leagues to the big leagues—and that it’s time for sports to be recognized as both a driver and reflection of social change.

The subtitle of your book is “How Politics Has Turned the Sports World Upside Down.” How have politics changed sports, and has it been for the better or worse?

It’s very different than it was just five years ago. A lot of the sports writing community has missed this, and missed it wildly. The sports world we’re looking at in 2013 is just different than the sports world of 2008. There are a lot of reasons why this is the case, but there are three that I think have been most transformative—and there are positives and negatives that we can pull out of all three.

The first is the 2008 economic crisis, the biggest recession in 80 years in this country. It turned the economics of sports on its head—there have been four lockouts in different years [including the NFL referees], as owners in different sports have tried to restore profitability. There have been fewer public subsidies for stadiums, which were one of the pillars of sports profits for the last generation. There have been crises in every country where the Olympic or World Cup decided to land.

The second one is the growth the LGBT movement in this country. We’ve gone from 2008—where every candidate running for president talked about marriage equality as if it was a plague—to 2013, when you have Barack Obama mentioning “Stonewall” in his inauguration speech. And this has been reflected in the world of sports. This has a particularly potent impact because sports—particularly men’s sports—have been a way in which masculinity has been defined, and more specifically a kind of masculinity that doesn’t show vulnerability, doesn’t show pain, and equates any kind of sensitivity with weakness and with being gay. This goes back to Teddy Roosevelt, who popularized the term ‘sissy’ for people who didn’t play violent sports.

So now, to see people like Steve Nash, Michael Strahan, Brendan Ayanbadejo, Scott Fujita, actually speaking out for LGBT rights, it has a very powerful cultural effect. The Vancouver Canucks just did a public service announcement about transgender awareness, and in the NCAA, a man named Kye Allums played for the women’s basketball team of George Washington—the first openly transgender player in the NCAA. These are huge changes in how we understand that we are diverse, both racially and in terms of our sexuality and gender.

The third thing that’s exploded in the last five years is the issue of the NFL and concussions and the recognition that playing the most popular sport in the country is a legitimate health hazard. You have [former] NFL players killing themselves—there have been four suicides in the last year—and this is something that’s become too much for the NFL to ignore. On media day at the Super Bowl, all the players were being asked—and I ask this when I speak to NFL players, too—“Would you want your son playing football?” Some say yes, some say no, but they all think about it. These are huge changes in how we look at sports and violence.

The other day, Baltimore Ravens safety Bernard Pollard said he doesn’t think the NFL will exist in 30 years due to these sorts of problems. What do you see happening?

I disagree with Bernard Pollard—I don’t think the game will be appreciably different than it is now. But I think it will be less popular, the same way that boxing is much less popular today. Fifty years ago, if you were the heavyweight champ, you were the most famous athlete in the United States. Now, I bet the overwhelming majority of sports fans couldn’t name who the champion is. It’s just not as popular.

So I think it’ll be less popular, and I also think that the talent pool is going to shrink as more parents keep their kids out of playing. You’ll see the NFL invest millions of dollars in urban infrastructure and youth football leagues, and it’s going to be the poorest kids playing football as a ticket out of poverty. This year, the four best young quarterbacks—Andrew Luck, RGIII, Russell Wilson, and Colin Kaepernick—all four of them excelled at multiple sports and came from stable, middle-class homes. Those are exactly the kind of players who won’t be playing football in 30 years.

You write that issues like this—the darker side of sports—often get overlooked in sports coverage. Why is this?

It goes back to the fact that many of the best reporters out there now work for outlets like the NFL Network, NBA.com—they actually work for the league. With ESPN, you have a hegemonic broadcast partner with the leagues. In any other industry, this would be seen as a conflict of interest, but in sports, it’s not, because sports are seen as fun and games. But the problem is that for a lot of people, sports are the way they understand the world—they’re the closest thing we have to a common language in this country. When you couple that with the fact that the people who are supposed to be the “watchmen” of sports, the media, are in bed with the people they’re supposed to be covering, that’s how you get scandals like Lance Armstrong and Manti Te’O. With these scandals that you see, so much time is spent doing what Bob Lipsyte calls “godding up” athletes—turning them into gods. And then when the gods fail, reporters tear them down, piece-by-piece, as a way to make them look like outliers, or bad apples, and keep the sensibility and profitability of the sport afloat.

One of the trends you mention is that recently, athletes seem more willing to use their platform to advocate for their political beliefs. Why has this been happening?

Well, in the 1960s, athletes were at the forefront of the fight for social justice. And not just athletes, but the best athletes: Bill Russell, Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor, Muhammad Ali, Billie Jean King, Martina Navratilova, Arthur Ashe. But in the ’90s, as corporate control really solidified over sports, it was a desert of any sort of courage in sports. What you’re seeing today is that, because of broader crises in society, and because of social media, you’re seeing a turn away from what’s called the “Jordan era.” People are finding their voice.

You actually write about how, in the age of Twitter, this could actually be an asset for athletes, in terms of cultivating their “brand.”

It’s true. All the players’ public relations (PR) people, business managers, even team PR people, they want the players out in the community, they want them out there, they want people to root for the players as individuals. It gets tickets sales up and increases watchability. But when you do that, you also run the risk that you’ll unearth that somebody has certain ideas about the world that they’re going to share—and sometimes those ideas are, to many people, disgusting. Like when then-Baltimore Orioles outfielder Luke Scott talked about his “birther” theories about President Obama, or when Denard Span, an outfielder now with the Nationals, tweets that he’d been watching those Newtown conspiracy videos. To me personally, these are disgusting beliefs, but they’re important too. Athletes are entering the public debate about certain issues, so now let’s debate them.

For you personally—someone who seems to be constantly criticizing and pointing out the distressing aspects of modern sports—why did you get into sports writing in the first place?

Before I had any interest in politics, I loved sports, and I still have that love. I grew up in New York City in the 1980s, and my room was a shrine to the stars of that time—Daryl Strawberry, Dwight Gooden, Lawrence Taylor, Keith Hernandez. I played basketball, I played baseball, I memorized the backs of baseball cards, I read sports books all the time, and I absolutely loved it all. I was at Game 6 of the 1986 World Series when the ball went through Bill Buckner’s legs, and I still have the ticket stub. So I’m a big believer that sports is like a fire—you can use it to cook a meal or burn down a house.

The reason why I write about it critically is that I consider myself a traditionalist when it comes to sports. I want to save it from its hideous excesses, and the way it’s used by people in power for their political means. So when people say to me, “You’re trying to politicize sports,” I say, “Don’t you see that sports is already politicized?” I want sports to be apart from politics, but as long as it isn’t, we need to point that out.

Do you find it difficult to root for athletes or owners whose political beliefs you disagree with? And do you root more for a player if you agree with them?

When I meet players, and I really respect their politics, and I think they’re courageous people—yes, I do root for them a little harder. Partly because I’ve gotten to know them, but also because I know how sports media works, that the more successful they are, the more people will hear what they want to say, and the more they can leverage this platform. So of course, I want people who are courageous and will use that platform to do more than sell sports drinks, I want them to have the brightest spotlight possible.

As far as athletes whose politics I don’t like, is it hard to root for them? I guess I’m grateful just to know what their politics are, and that they have spoken out. I’ve never actively rooted against somebody because of his or her politics. Even someone like Tim Tebow, I actually like him. I just happen to think he can’t do that really important thing that quarterbacks need to do—which is to throw a football.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)