The New Yorker Editor Who Became a Comic Book Hero

The amazing tale of a determined art director who harnessed the powers of the greatest illustrators around the world to blow kids’ minds

:focal(415x76:416x77)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/b3/02b3de31-2058-495f-8241-5b266ed5a5a4/davissmithsonianmouly200dpi.jpeg)

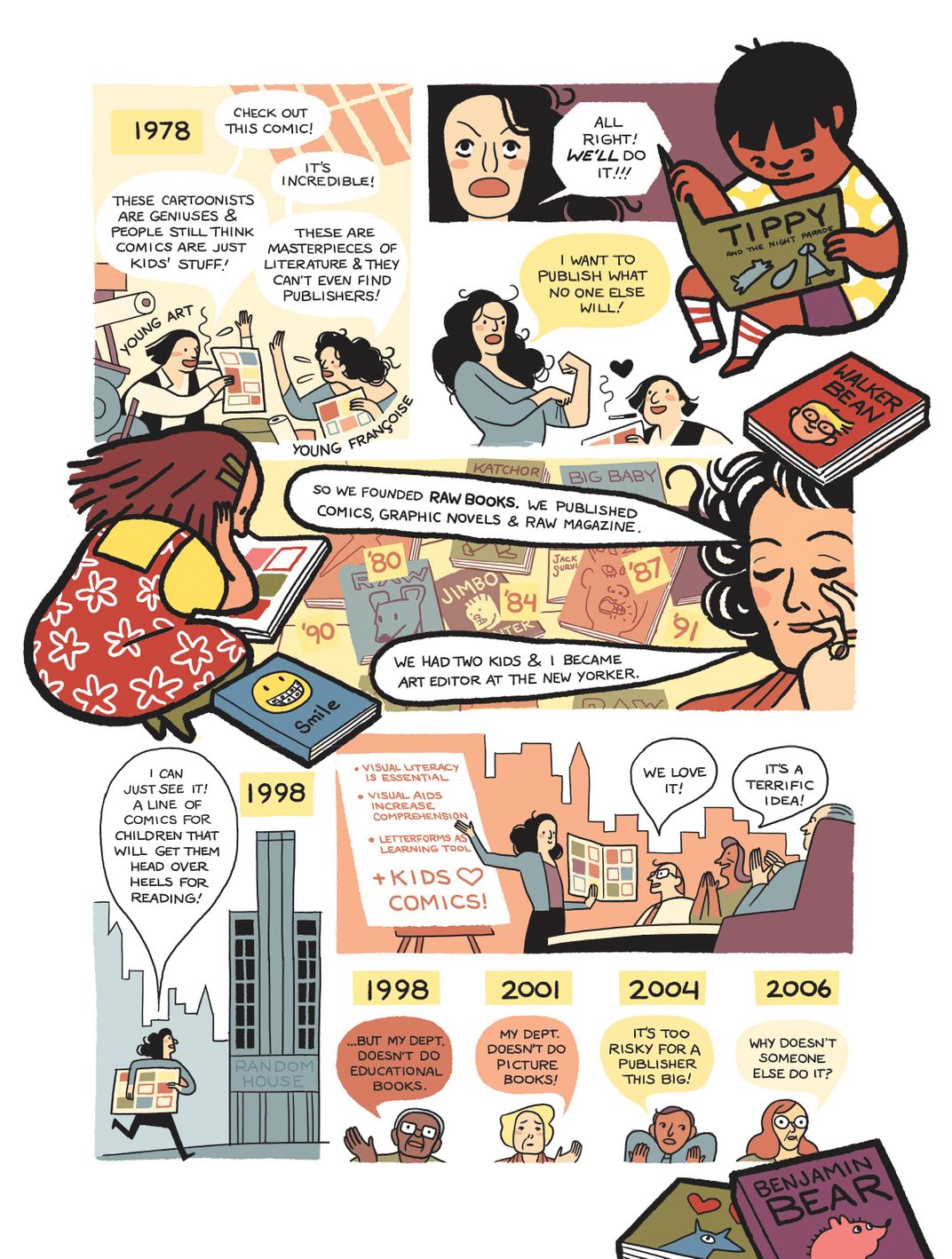

Comic books? Educational? The very idea is comical to anyone familiar with the 1954 Senate subcommittee investigation that linked juvenile delinquency to horror and crime comics. The politicians dealt the industry a staggering blow that it overcame only after superheroes, plus corny teens like Archie and a rascal named Dennis, came to the rescue. Still, comics are seldom associated with literacy. But Françoise Mouly started Toon Books precisely to get more young people reading, and thinking, and enjoying the printed word, lushly illustrated and handsomely bound as well. “It’s something they will hold in their hand and they will feel the care we put into it,” Mouly says. Schools are catching on, spicing up reading lists with Toon titles (43 published so far). Mouly acknowledges she’s putting teachers in a bind that is sort of funny: “Can you imagine having to go see your principal and say, ‘I’m going to spend money on comic books!’” – The Editors

**********

Smithsonian correspondent Jeff MacGregor recently sat down with Françoise Mouly in her Toon Books offices. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

How did you come up with the idea for Toon Books—comic panels—as a mechanism for teaching reading?

When I became a mother and was spending lots of time reading marvelous, wonderful books with our kids, I reached a point where I realized there are not [all of the] books I would want to have as a parent. We had spent the time reading children’s books [and French] comics. I would come back from France with suitcases of the books my kids wanted. They loved comics, partly because it gave them some things they could decipher for themselves before they could read the words.

And it had been my impulse [to read comics] when I was first in New York and my English was very poor and I had difficulty reading real books and reading the newspapers. I had a command of English, but not the way it’s used colloquially. Comics, because they are a multimedia form of communication—you get some of the meaning from the words, from the size of the lettering, from the font, from the shape of the balloon, you get the emotion of the character—it’s almost like sketching out language for you. Kids don’t just sit there and wait for knowledge to be shoved into their brains. Reading is making meaning out of squiggles, but the thing with comics is that no one has ever had to teach a child how to find Waldo.

I realized this was a fantastic tool. It worked with our kids. “Well I learned to read,” says Art [Spiegelman, Mouly's husband and illustrator of Maus], “by looking at Batman.” But when I looked, I saw that the educational system was prejudiced against comics. I went to see every publishing house and it was a kind of circular argument. It was like, “Well, it’s a great idea, but it goes against a number of things that we don’t do.”

Was there ever a moment when you were seriously considering giving up?

Oh I gave up! By the end of 2006, beginning of 2007, I had given up. That’s when everybody that I had talked into it was like, “Don’t give up! Please don’t give up! Keep at it!” That’s when I investigated: What if I do it myself? I’m much more nimble because I have very little staff. At some point I talked to Random House again when I was doing it myself. “Yeah, we can do it, we’ll do them in pamphlets, you’ll do three a month, so you’ll do 36 a year of each title and you should do like five titles.” I was like, “No, sorry! I can’t!” That’s not the same attention. You can’t produce good work.

What’s the best part of being a publisher?

I can make books happen without having to explain and justify. The other thing is that if I had been picked up by one of those big houses, that would have been the end of me. I would have been wiped out because I launched in 2008, just when the economy collapsed. So guess what would have been the first thing to go.

Are the books accomplishing what you set out to do?

Yeah, the feedback we have gotten from the teachers, how well it works. I was talking to someone, she loves books, her kid loves books, but her granddaughter who is 8 years old basically was like, “Eh, that’s not my thing.” I sent her a set of Toon Books because she was always advocating for reading and it was just breaking her heart. The granddaughter took [the books], locked herself in a room, and then after that was like, “Grandma, let me read this aloud to you.” She was reading in the car, taking a book everywhere, taking it to the restaurant. She wanted to read to them all.

Do you think it’s more useful to have these in school or to have them in the home?

You cannot, in this day and age, get them in the home. Everybody [used to] read newspapers, everybody read magazines, everybody read books. There were books in the home. Not media for the elite, [but] mass media. Books and magazines were as prevalent then as Facebook is, as Twitter is. That’s not the case anymore. Most kids at the age of 5 or 6 don’t see their parents picking up a newspaper or a magazine or a pulp novel or literary novel. So you know, [it becomes] “You must learn to read.” It’s completely abstract.

The libraries are playing an essential role. The librarians and the teachers were the ones removing comics from the hands of kids back in the ’60s and ’70s. Now it’s actually almost the other way around. Most kids discover books and comics, if they haven’t had them for the first five years of their lives, when they enter school. Because when they enter school, they are taken to the library. And librarians, once they open the floodgates, they realize, “Oh my God, the kids are actually asking to go to the library because they can sit on the floor and read comics.” You don’t have to force them — it’s their favorite time. So then what we try to do, when we do programs with schools, is try to do it in such a way that a kid can bring a book home because you want them to teach their parents.

Is there an electronic future for these?

One of my colleagues was saying e-books replaced cheap paperbacks and maybe that’s good. A lot of this disposable print can be replaced by stuff you didn’t want to keep. But when I read a book, I still want to have a copy of the book. I want it to actually not be pristine anymore, I want to see the stains from the coffee – not that I’m trying to damage my book, but I want it to have lived with me for that period of time. And similarly, I think that the kids need to have the book. It’s something they will hold in their hand, and they will feel the care we put into it. The moment I was so happy was when a little girl was holding one of the Toon Books, and she was petting it and closing her eyes and going, “I love this book, I love this book.” The sensuality of her appreciation for the book, I mean, that’s love.

I picture you as a little girl in Paris, your head is in a book. And you’re sending this out [now], you’re sending these out to her.

It’s true. Books were my lifeline. I’m not worried about my friends’ children. I know that they have loving parents that will take them on their lap and read to them and they’ll come out OK. But I believe that we have a responsibility to every other kid whose parent is working two jobs and doesn’t necessarily have time to take their kid on their lap— who doesn’t have already access to books. Those kids are thrown into an educational system where the poor teachers don’t have a chance to take the kids individually and do reading time. What is gong to be their lifeline?

With all our books, we do lesson plans of the ways to not just read the book, but reread the book. That’s what I remember from when I was a kid. [I had] an illustrated fairy tale and I remember spending hours not just reading the stories again and again, but also looking at the pictures and seeing how they were different and they echoed and didn’t echo each other. Kids naturally want you to read them the same book every single night to the point where you’re going crazy. But they get something different every time. That’s fundamental, and there’s a way in which those books become building blocks and those have to be good. Those can’t be derived products where you do 15 a month. Those have to have as much substance as we had when we read Alice in Wonderland. The ambition is not to make something that will want to be read, but to make something that can be reread.

What’s next? What do you do after all this?

I’ll find that as I am doing it. When we launched the Toon Graphics, I didn’t realize that we would do books for 8- to 12-year-olds and there would be a book of fantasy and there would be a fairy tale and there would be Greek mythology. Now I’m looking back on it and saying, “Oh my God, we’re hitting all of the stories that we all need to have and share.” I’m still figuring it out one book at a time.

Are you a transformative figure in the history of comics? You became the vehicle that moved comics out of the fringe into the center.

I can’t be the person saying that. All I know is, I know to trust [myself], and that has served me well. If I see something, how something could be, I should go out and do it. I shouldn’t ask permission from anybody. The thing to stay away from, for me, is what unfortunately is too often the case in publishing, that they all want to publish last year’s book. I want to publish next year’s book! The book of the future.

Your love story with Art is one of the great love stories.

One of the things that is really meaningful to me is the fact that I’ve been able to literally marry my love for Art, my love for what he loves, everything I learned as a mother. Most people are asked to separate their private lives from their work lives. I am so privileged that my work life is what I love and I love what I do in my work.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)