Doug Aitken is Redefining How We Experience Art

The artist uses video, music, mirrors, railroad cars, even entire buildings to create works that make every viewer a participant

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Aitken-ingenuity-portrait-631.jpg)

It’s 4:39 in the afternoon, the sky’s sliding sun is slicing in half the black canal 100 feet from the front door, and Doug Aitken’s house is about to explode.

“It’s about that time,” the artist agrees, glancing at the clock on his laptop. When the day burns down its fuse to dusk, the frescoed walls of the living room will atomize, the staircase that is a walk-in kaleidoscope will splinter into shards of twilight, and the copy of Ulysses standing on the bookshelf would go up in flames if it were paper rather than a doorknob that pushes open a secret entrance to the bathroom.

None of this will raise the eyebrow of anyone familiar with Aitken’s work. Vanishing boundaries, fractured space and clandestine passages have been the language of his art for two decades. Age 45-going-on-overgrown-beach-kid, at the moment he sits barefoot in his bomb of a house preparing for his upcoming new work Station to Station and has just come off the acclaimed Mirror, which overlooks Seattle, with its incessant echoes of city and wilderness laying siege to the coordinates of common perception. The limits of what we perceive are the concern of everything Aitken does. This includes building a house that mirrors himself, and conjuring bigger-than-life creative wonders around the world that invite not just our surveillance but occupancy. Aitken’s mission is to shatter all the modes by which we shackle our common dreams.

He looks up from the laptop. Tick, tick, tick, goes the world outside: Can you hear that? the smile on his face says. All the old ways of imagining are about to go boom.

***

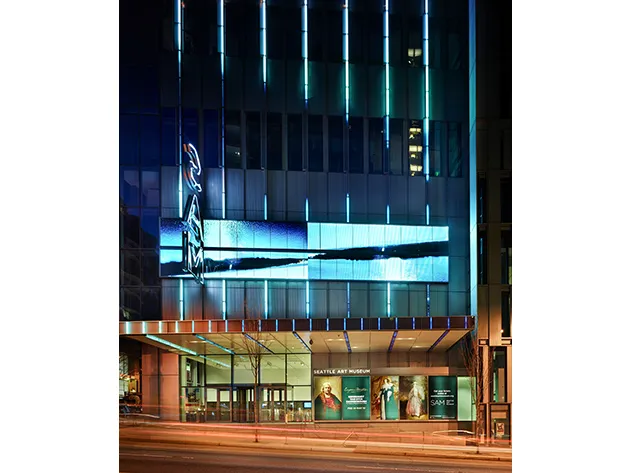

Bound by columns of rocketing light and affixed glistening to the side of the Seattle Art Museum, Mirror is what Aitken calls an “urban earthwork.”

LED tiles a dozen floors high and wrapping around the museum’s corner cohere into a single screen that flickers hundreds of hours of film of the surrounding sea and mountains, ascending buildings and asphalt junctions: the vapors of a city’s life and the plumes of a city’s reveries. Sensors outside the museum endlessly collect data of whatever’s happening that moment in downtown Seattle at the intersection of Union and First—traffic jams and invading weather fronts—which then is translated by computerized projectors into algorithms that dictate a selection from footage, already shot by Aitken’s team of cinematographers and editors and designers and engineers, of the surrounding Pacific Northwest. Blossoming and collapsing, the images are shuffled and spindled, sputtering up and down the screen and across its length in incrementally transforming variations. Leave and when you return in a couple of hours what you see will resemble what you saw before but not precisely, in the same way that the light of one moment is never exactly the light of the preceding moment.

“Or,” Aitken elaborates, “it’s a kind of map” that evolves out of the ingredients of its own place. If part of our relationship with any mirror is the act of gazing into it—an observer on the other side of First Avenue observes Mirror being observed by those it observes back: skyscraper-art as an enormous Chinese puzzle-box—then the piece typifies how Aitken’s work isn’t “fixed or frozen, not something you just see and interpret. Mirror constantly changes to invisible rhythms, like a series of rings radiating out. It creates an infinite library of musical notes that can be played and repositioned, reordered.” Aitken often talks of his art in musical terms, Mirror’s unveiling last spring accompanied by the vertiginous siren call of composer Terry Riley, who regards Aitken as a kindred soul. “He morphs the ordinary into the extraordinary,” says Riley, “carving out a singular cinematic art.”

Doug Aitken is the artist of disappearing dimensions and the psychic exodus. Pursuing a new sense of wonder, long ago he abandoned more reasonably circumscribed canvases for one the size of a planet; using music, film, construction design, pixelated theatrics, willing participants and no small amount of fast-talking showmanship, he creates videopaloozas of murmuring sonics and drifting visuals—equal parts Antonioni, Eno and Disney. Since the 1990s, beating the calendar by a decade, he’s been laying 21st-century siege to 20th-century structures, “eliminating the space,” as Washington, D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum acting director Kerry Brougher puts it, “between the object and viewer—blurring lines and turning art into a multifaceted, collaborative experience.”

Growing up in Southern California in the 1970s and ’80s, having already cultivated an adolescent habit of making art out of whatever he found lying around the garage or beach, Aitken got a scholarship to Pasadena’s Art Center only to feel stymied by any drawing that had a frame. Embracing a tradition (if that can even be the word for it) belonging to not only Riley but graphic conceptualist John Baldessari and experimental auteur Stan Brakhage, in the ’90s he moved to New York, where he lived and worked in an unfurnished loft, confronted by the emancipation of having nothing.

“I was stepping in and out of whatever form was best for each idea, not always successfully,” Aitken allows, “trying to make something where you’re inside the art. But then, you know, the question is how to create a language for that.” In his 1997 breakthrough Diamond Sea the dynamism of Namib Desert imagery clashed with the static nature of its composition, while, in this century, Migration bore witness to deserted motels on the edge of civilization invaded by horses and buffalo and albino peacocks, foxes nosing the remnants of unfinished jigsaw puzzles and owls gazing at the blinking red message-lights of telephones. Sleepwalkers took over a block of Manhattan, beaming out from the Museum of Modern Art and catching up 54th Street’s pedestrians in its somnambulant dramas: “‘Oh, look,’” Aitken delightedly recalls overhearing a hotel doorman tell a cabbie as he pointed out the movie overhead, “‘here’s the best part.’”

It’s easy to be so dazzled by the sheer audio-digital, interactive spectacle of Aitken’s work—“tech-fueled, all-night, glow-in-the-dark pop-art,” effused Wired recently—as to miss a point that eludes glib interpretation anyway. With the participation of actors such as Tilda Swinton and Donald Sutherland and musicians like Cat Power and artists like Ed Ruscha, Aitken dashes film’s confinements against its potential as a cosmic portal. “I feel the ceiling of the media,” sighs the artist, caught up in his own paradox, whereby the profound minimalism to which he’s instinctively drawn demands a span epic enough to accommodate it. After years of making notes and throwing them away, last year he turned inside out the Cinerama of the ’60s (the decade during which Aitken, who talks about “freakouts” and “happenings,” was born) and wrapped it around the Hirshhorn’s entire exterior, “trying to figure out,” he recounts, “how large-scale an installation I could create out of the most concentrated contemporary art form, the three-and-a-half-minute pop song.” Song1 unspooled not just beyond what anyone could register in a single sighting (“I Only Have Eyes for You” was the song) but past whatever 360 degrees is private to each of us, turning the museum into a hegira swallowing itself, ceaselessly slithering toward a final epiphany never reached.

This autumn’s Station to Station was a train turned roaming installation and light show, a flashing, beeping movie-screen-cum-music-box crossing the country on rail—or a “nomadic film studio,” as Aitken called it, that gathered and showcased from stop to stop the work of cultural insurrectionists like Kenneth Anger, Thurston Moore, Jack Pierson, Raymond Pettibon, Alice Waters and the Handsome Family. With its boxcar visions and orchestral cabooses, traversing what we’ll quaintly call the New World (a highly relative term when discussing Aitken), the artist’s magical mystery tour stopped off at metropoles and mid-level hamlets and ghosts of towns that don’t know they’re ghosts, from Pittsburgh to Kansas City to Winslow, Arizona, indulging the various agitations of its passengers. “Someone like Giorgio Moroder would say, I’d love to make the train-car my instrument and record a soundscape through the desert until we reach the Pacific. Or Beck wanted to work with gospel singers. In the meantime we’re streaming 100 short films coming through like a tsunami.” It was, Aitken grins, “a freakout.” If there was a flaw in this, it’s in the title, courtesy of the David Bowie song: Sooner or later trains run out of stations and stop, whereas ideally Aitken’s Ambient Express would wander the continent forever. Sometimes he’s tethered by the same coordinates as you and I after all. “Failure,” he shrugs, “is something you kind of grow off of,” which is to say next time he’ll get himself a molecular transporter with a wormhole attached. “Often I find, when I’m making work, that I’m most interested in its weaknesses. How it’s unstable. Whether there’s too much information, or it’s fuzzy.”

***

The house off the little walkway in Venice, California, is Aitken’s most personal assault on our peripheries. “We have this idea,” he says, “that life is a beginning and end that contains a convenient narrative, whereas I feel more akin to living in a collage”—to wit the abode forged from the rubble of an old beach bungalow.

Hidden by foliage and a surrounding partition, the house can’t be seen at all until once beyond a gate, from where the front door is suddenly only a few steps away. In other words a visitor never has any sense of the house’s exterior, and from the inside the house conspires to become the “liquid architecture” of Mirror and Song1, blowing away the delineations between outer and inner. The hedges beyond the windows have been painted on the walls so that, with that blast of 4:39 late-afternoon light, the walls appear to disappear, as if the house has turned inside out; and on the right night with the right full moon, the stairwell of angled mirror and glass is flooded with lunar fire, the steps up to the roof an ascending xylophone making music like the tiles of the downstairs table. The earth beneath the house is miked to amplify the geologic babble of the beach: “You can turn on Channel 2,” Aitken says, adjusting the knob of a hidden amplifier, “and mix the house.”

It is a trompe l’oeil house fabricated to create a space for Aitken that’s completely private, to the extent of nearly being invisible, while evoking as little as possible the actual physical confines of space per se. This corresponds with the he’s-everywhere-he’s-nowhere persona of Aitken himself; if it would seem the artist’s audacities require an ego to match, he struggles to remove himself from not only his own work but his own life as the public perceives it. When he says, “I don’t want to be part of the club, I want to make my own universe,” it’s not bravado but an aspiration he figures everyone shares, and wonders why not if they don’t. He speaks in futurist koans and canny non sequiturs, in terms of systems and liquid architecture and the constellations of invisible beacons, as if he assumes it’s a shared language everyone intuitively understands; he also edits out whatever is intimately at stake—information he reflexively regards as overly self-involved no matter how routine. The most banal revelation can be couched in strategic vagaries. Peering at his surroundings, he’ll say, “I guess we’re in part of my studio right now,” which means we’re almost definitely in his studio. “I was growing up in some beach city like Redondo Beach or something” means, I grew up in Redondo Beach.

A recurring motif is 1968. This is both the year that Aitken was born and a year of tumult—“a moment,” Aitken calls it, “of cultural shattering.” The only child of restless parents constantly hopping terrains or thinking about it (Russia one year, Brazilian rainforests another), which may account for his itinerant temperament, Aitken remembers his father taking him to Tarkovsky movies and the long quiet rides home four hours later as Solaris was sinking in. Like anyone who’s raised in Southern California but not part of Hollywood, Aitken was familiar enough with production shoots and moviemaking as a daily reality to find it existential rather than glamorous. Hanging out with friends at the water’s edge when he was 10, one day a film crew ran everyone off the sand except Doug, who a year later was watching some beach movie that could have been called Lifeguard or something (as Aitken might describe a movie exactly titled Lifeguard), with its lonely eponymous hero pondering his shoreline exile, when a familiar kid in the distance peered back. “Just as Sam Elliott’s voice-over comes on, as he’s looking out at the bleak overcast afternoon and says, ‘Sometimes there just ain’t...nothin’...out there,’ the camera pans across and,” Aitken laughs, “I see myself.” There in the dark of the theater the two boys gaped at each other, and Aitken realized the movies have a secret: They think we’re the movie.

In that spirit Mirror translates us in its terms as we translate what we see in ours, broadcasting back to Seattle not so much a reflection as a Rorschach. “Doug spins art into a continually unfolding experience,” says Brougher, “that incorporates our memories and sensibilities with life’s landscape,” and which rejects, he might add, not just limits of form and function, time and space, but those conditions by which subjective dogmas, including Aitken’s, obligate our thinking. When Jen Graves, columnist for Seattle’s alternative newspaper The Stranger, writes, “We’ll have to see whether we see ourselves in [Mirror], whether we feel ourselves in it, or whether it is a monument instead to the flatter aspects of mirrors,” Aitken might be the first to agree. If his art, as Riley concludes, “is filled with ritual and magic, bringing together art and the public in a celebratory way,” it intends as well to render all that once was solid and melted into air back into some other solid thing, made from the old and re-formed anew—weightless, ever expanding even as its essence becomes more distilled, and finally ours to inhabit or vacate, per the roaming disposition of its creator.

“In art,” says Aitken, riding the train of his provocations with the wind of the imminent at his back, “ingenuity might not always mean cracking the code. I think we’re coming into a ’68 moment when the bedrock of modern creativity is being challenged, when the idea is to create a space where there’s less...safety. I hope my work is always moving on into tomorrow and the next day, and it doesn’t really give me a lot of time for stasis or slowing down. You know? We're all kind of racing toward martality, doing the best we can."