Designing Buildings For Hot Climates, Cold Ones and Everything in Between

A decade’s worth of sustainable projects by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels and his firm, BIG, are now on display at the National Building Museum

There is a reason the hillsides of Santorini and other Greek islands are speckled with Cubist whitewashed homes. The white color reflects heat, and the flat roofs make for cool, breezy retreats in the evening, Bjarke Ingels explains to the gathered press. The Danish architect is sharply dressed in a fitted suit, his hair a meticulous mess. In the Arctic, the igloo is the dominant form of architecture, he adds, because its spherical shape, with relatively little surface area in respect to volume, minimizes heat loss. And in some villages in Yemen, buildings have peculiar chimneys that collect wind to create natural ventilation.

"Across the planet, people have found ways to work with the locally available material and techniques to respond to the local landscape and climate in ways that optimize human living conditions," he says.

Yet, nearly a century ago, these distinct architectural styles started to give way. Architects became less concerned about daylight, the thicknesses of walls and a building's orientation when they could rely on advances in technology, such as electricity, air conditioning and mechanical ventilation. "In the end, architecture was just a big boring box," says Ingels, "a container of space with all the quality being pumped or tube-fed from a room, like a gas guzzling basement, full of machinery."

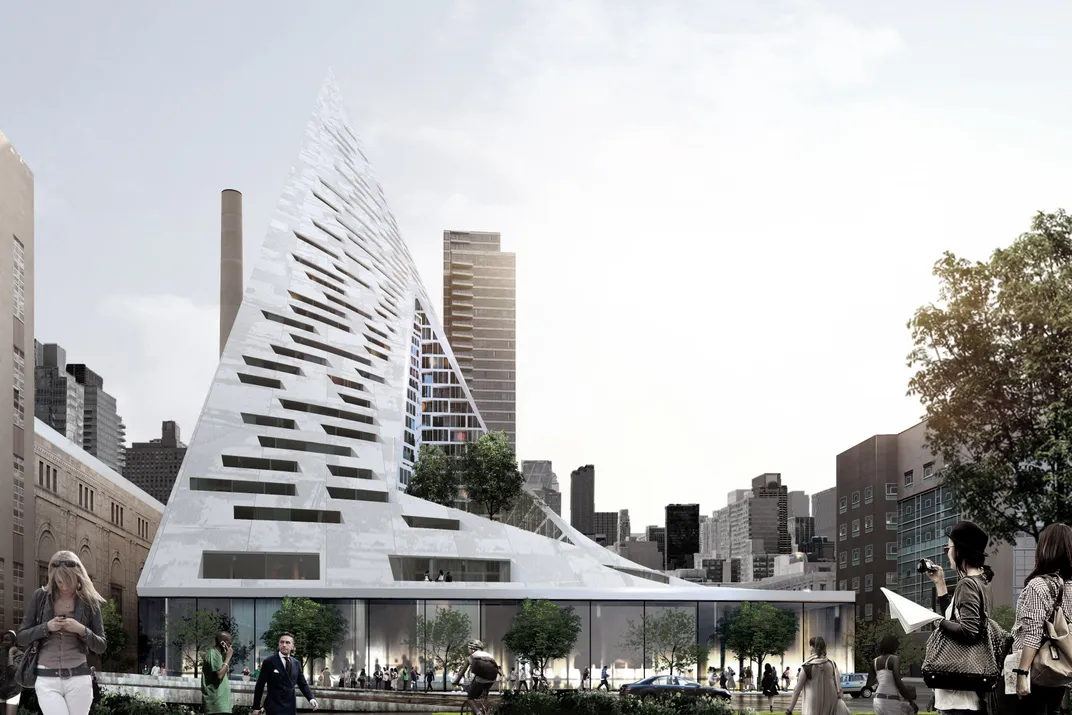

Ingels founded BIG Bjarke Ingels Group in 2005, and the design firm is working to reverse this trend. "The fact that we can actually model, calculate and simulate the environmental performance of a building allows us to bring a lot of the qualities that are now delivered mechanically back into the permanent attribute of the design," says the architect. The pleated façade of an energy headquarters that BIG is constructing in Shenzhen, China, for example, cuts air conditioning needs by 30 percent. The group's Hualien Resort and Residences look like manmade mountains with strips of green roof that keep the balconies 5 degrees Celsius cooler than they would be with conventional roofs. "We call it 'engineering without engines,'" he says.

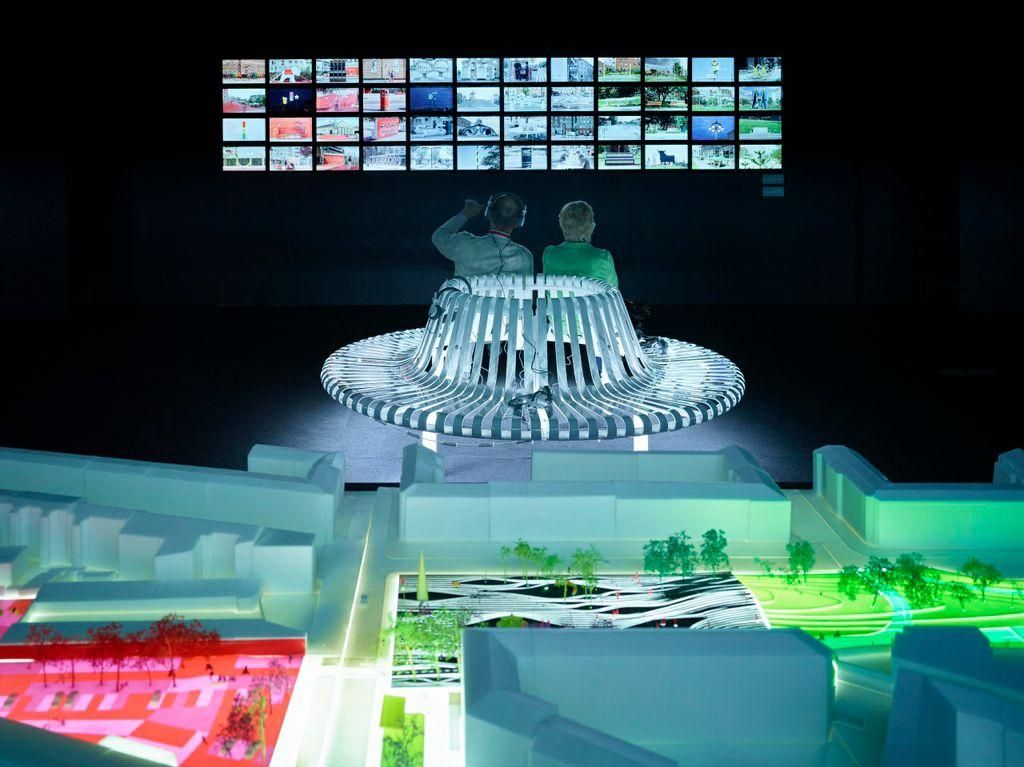

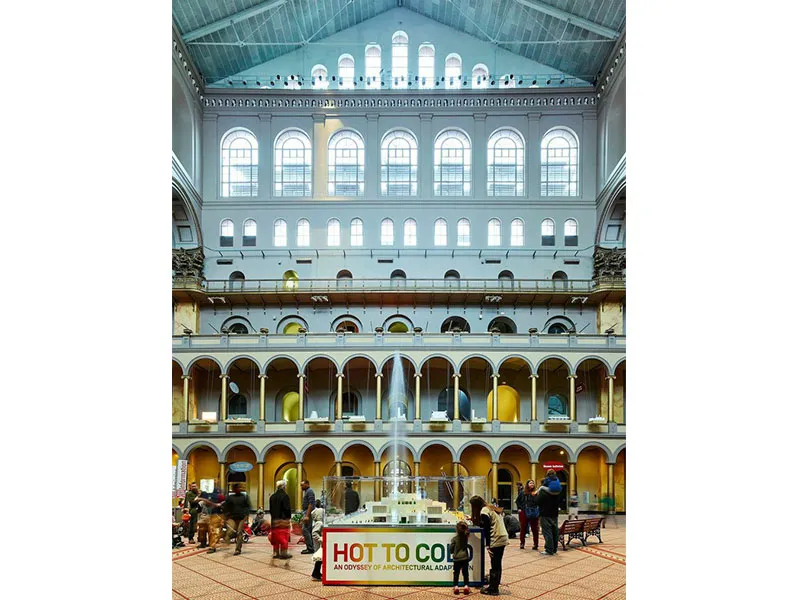

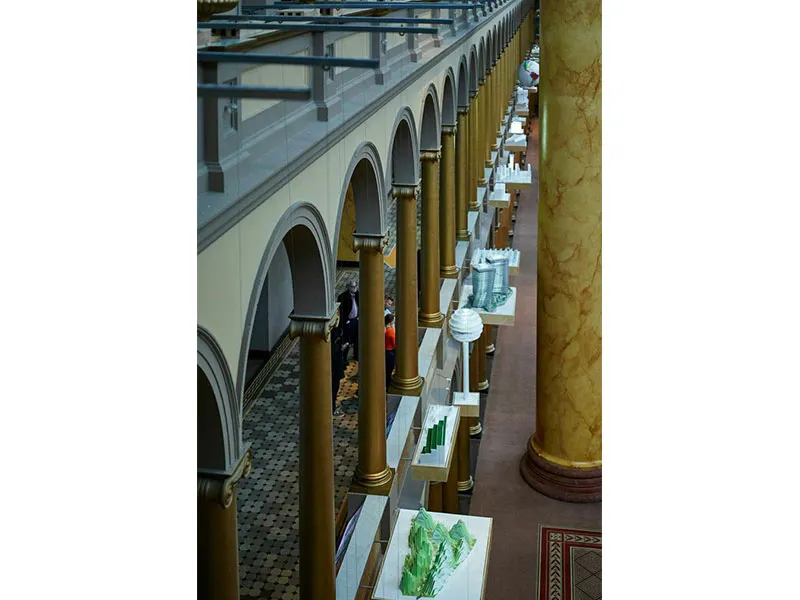

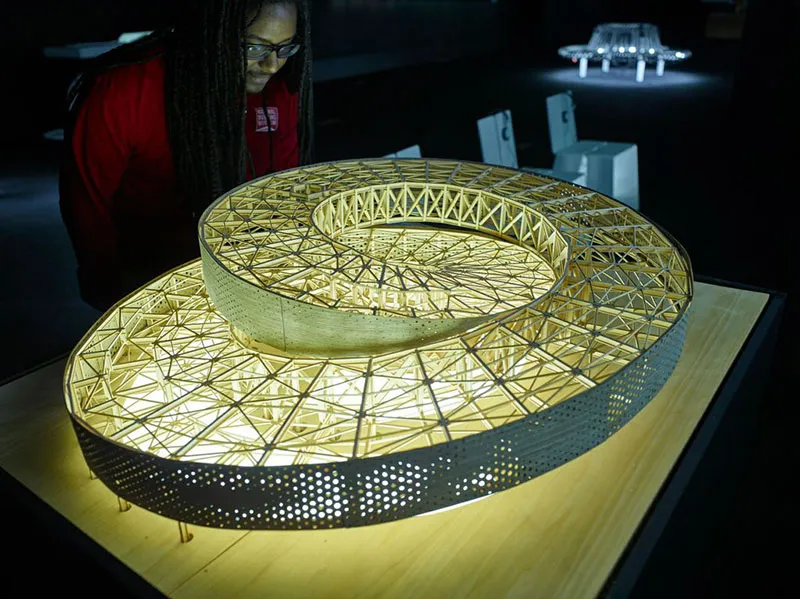

The National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., is hosting BIG's first retrospective since the firm established an office in New York City (expanding from Copenhagen) nearly five years ago. For the exhibition, "Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation," the architectural models of 60 of the firm's projects—some proposed, others under construction or completed—are hanging from arches along the museum's second floor balcony. From the ground floor, visitors can see that the bases of the models are color-coded from red to blue, like a heat map, starting with those buildings in the arid deserts of the Middle East and moving to the more temperate climates of New York and Copenhagen and finally to the Arctic regions.

"As you journey across the globe in this 800 foot walk, you'll see that in the extreme climates when it is very warm or very cold, the climate becomes the one condition that overshadows everything else. The architecture becomes all about responding to the climate. But when we reach the more temperate climates or the milder climates, other factors like culture, heritage, politics and economy take over and become the main driving forces," Ingels explains on a tour. "The whole exhibition is really trying to highlight the environmental and the social as the two crucial dimensions of architecture."

In his work, ranging from museums to housing developments to power plants, Ingels strives for what he calls “hedonistic sustainability,” meaning that his buildings are environmentally sound while still being enjoyable. It is the playful details of his projects, after all, that the architect points out in his walk-through of the exhibition. The condos he designed for a complex in the Bahamas that Tiger Woods is developing have pools cleverly sunk into their balconies and contained by aquarium glass. "If you are skinny dipping at night, you need to have a fitness regime," Ingels jokes. The Lego Brand House in Billund, Denmark, has several terraces with public playgrounds; the building is designed in a way that every element could feasibly be constructed with Lego pieces. And, the angled roof of the Amager Resource Center, a power plant in Copenhagen, doubles as a manmade ski slope. "It is twice the length of a typical Olympic halfpipe," he says. "You might have noticed that Denmark won zero medals in Sochi. We hope to redeem this."

"BIG has a very distinctive voice," says National Building Museum curator Susan Piedmont-Palladino, in a press release, "and the experience our visitors will have will be very direct, as if the architect is talking, telling stories directly to them."

The walls of BIG's architectural models do talk, in a way. After circling the exhibition, one clear story takes shape. That is, buildings that are sustainable and work within their natural landscapes make the most intriguing ones.

"Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation" is on display at the National Building Museum through August 30, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)