Dear Sir, Ben Franklin Would Like to Add You to His Network

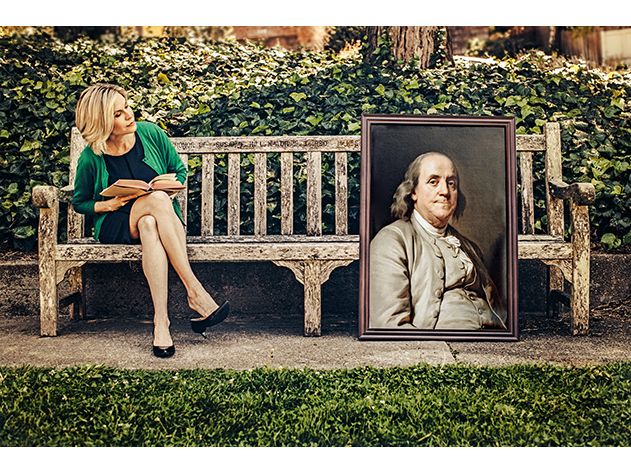

Historian Caroline Winterer’s analysis of Franklin’s letters applies big data to big history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Winterer-ingenuity-portrait-631.jpg)

In July 1757 Benjamin Franklin arrived in London to represent Pennsylvania in its dealings with Britain. With characteristic dry humor, Franklin, then 50, had written ahead, warning his longtime correspondent William Strahan, a fellow printer, that he might appear at any moment. “Our Assembly talk of sending me to England speedily. Then look out sharp, and if a fat old Fellow should come to your Printing House and request a little Smouting [freelance work], depend on it.”

That trans-Atlantic journey effectively marked Franklin’s debut on the world stage, the moment this American inventor-publisher-aphorist-leader—but not yet the wise old cosmopolitan founding father—first directly encountered the Old World intellectual elite in the midst of the Enlightenment. And for that reason 1757 is the starting point for a groundbreaking investigation of Franklin in the world of ideas. At Stanford, historian Caroline Winterer is heading up a computer-powered effort to trace the interconnections—what we in the era of Facebook recognize as social networks—that would eventually link Franklin to the most prominent intellectuals and public figures of his day. The study is part of a larger endeavor at Stanford, the Republic of Letters project, to map the interactions of the Enlightenment’s leading thinkers, among them Voltaire, philosopher John Locke and astronomer William Herschel.

“We are seeing Franklin when he was not the Benjamin Franklin,” Winterer, who is 47, says one day, looking up from a computer in her office overlooking the Spanish Mission-style buildings of the university’s main quad. On-screen bar graphs display a welter of data, including the ages and nationalities of her subject’s most active correspondents. “This project restores him to the story of the world.”

To be sure, Franklin was on his way to becoming a giant at home by 1757. His publishing business was flourishing; the Pennsylvania Gazette was the leading American newspaper, and Poor Richard’s Almanack was a staple of colonial bookshelves. He had laid the groundwork for the University of Pennsylvania and the American Philosophical Society. His brilliant experimental work on electricity had been published. But computer graphics and maps representing Franklin’s early correspondence add new particulars to our understanding of Franklin’s gradual entry into Enlightenment networks. He “does not stand out as a new, glittering species of American, the lowly provincial rocketed into the international arena of European intellectual and political life,” Winterer concludes in a new scholarly paper. “Rather, Franklin takes his place in a long sequence of British-American engagements in the republic of letters.”

The research, although still in the early stages, is stirring controversy among scholars because of its heavily quantitative approach—Winterer and co-workers don’t even read the Franklin letters that their computers enumerate. But the work is also winning praise.

The Harvard historian Jill Lepore, author of a new study of Franklin’s sister, Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin, says Winterer’s research is “revolutionary.” All too many digitization efforts, Lepore adds, “tell us what we already know—that there are more swimming pools in the suburbs than in the city, for instance—but the mapping in the Enlightenment project promises to illuminate patterns no one has seen before.”

Winterer’s work, says cultural historian Anthony Grafton of Princeton, increasingly will demonstrate the potential of what he calls “spatialized information” to “sharpen our understanding both of the culture of the British Atlantic and of the historical role of Benjamin Franklin.” And the promise of the approach is virtually limitless—it could be applied to historical figures from Paul of Tarsus to Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama.

In the initial phase of their research, Winterer and colleagues, including doctoral candidate Claire Rydell, draw on Franklin’s correspondence between 1757 and 1775, when Franklin returned to Philadelphia a committed partisan of American independence. During that time, his correspondence more than tripled, from around 100 letters a year to more than 300. At the Stanford Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA), researchers pore over an electronic database of Franklin’s correspondence, edited at Yale and available online. They painstakingly record data from each letter Franklin wrote or received, including the sender, recipient, locale and date. A separate database tracks individual senders and recipients. These two data sets are fed into a customized computer application for processing into charts, maps and graphs that allow the research team to search for patterns and interrogate the material in new ways.

In that 18-year period, as Winterer’s quantitative analysis documents, Franklin’s most prolific correspondents were not the movers and shakers of the European Enlightenment. He was not communicating with leading scientists of the Royal Society of London, the French intellectual elite or learned figures from around the Continent—with whom he would later engage on an equal footing.

One of the major ways that we understand Franklin, historian Gordon S. Wood states in his 2004 study, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, is that “He was undoubtedly the most cosmopolitan and the most urbane of that group of leaders who brought the Revolution.” A goal of the new Franklin research, Winterer says, is to accumulate data to test and measure this idea of Franklin.

What Franklin was doing at this early stage, her analysis shows, was writing primarily to James Parker, a printing partner in New York; David Hall, a fellow Philadelphia printer and business partner; Isaac Norris, a leading Pennsylvania politician; William Franklin, his son; and Deborah Franklin, his wife. He was dispatching letters mainly to Americans in the colonies and a handful of correspondents in England. Four hundred of Franklin’s outbound letters, mainly from London, were sent to Philadelphia, 253 to London and 145 to Boston. While he received 850 or so letters from correspondents in America and 629 from England, he received only 53 from France, 29 from Scotland and 13 from the Netherlands.

“We perceive Franklin as a star at the center of a galaxy,” Winterer says of Franklin’s role in the era’s intellectual firmament. “This data restores Franklin as a bit player.”

Even so, the metrics reveal the trending velocity, as it were, of Franklin’s correspondence. If one were to take a snapshot at two points, the year 1758, for instance, shows that letters in substantial numbers were directed to Philadelphia, London and Boston. By 1772, Franklin was sending increasing amounts of correspondence not only to those three cities, but to Edinburgh, an important locus of Enlightenment thought, and, significantly, to Paris—now among the top destinations for his letters. He had broadened his American network, too, incorporating locations including Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Savannah, Georgia.

***

The research is at the frontier of what’s known as the digital humanities, an approach that has been a boon for younger scholars who are at home in this new world. In temporary trailer space this summer, while CESTA offices were renovated, a small army of graduate students and computer gurus coded metadata from letters and other sources, their backpacks and flip-flops strewn around the floor. Students hunkered down over laptops, not a book in sight. In one corner, four researchers engaged in a furious game of foosball.

Although Winterer has gained a measure of academic fame for digital studies, she does not see herself as a techie, and says she limits her time online. “I tend to be somewhat technology averse,” she says.

The past, she says, exerted a strong hold on her from childhood. Her parents, oceanographers at the University of California at San Diego, “drove around California’s deserts and mountains when I was a kid,” she recalls, “narrating the big geological story of the landscape.” The experience of “pondering the past in a fleshed-out way (either in the age of T. rex or Franklin),” Winterer adds, “struck me then, as it does now, as an awesome exercise in the imagination.”

She first began to rely on computers as a graduate student in intellectual history at the University of Michigan in the 1990s. “The go-to resource for scholars became their computer screen and not the book. Computers allow you to do the natural jumping around that your mind does,” says Winterer. Also, computer models make it easier to see complex data. “I am a very visual person.”

In a break with traditional practice, Winterer and her colleagues have not attempted to read each letter or account for its contents. “You are eating the food and forcing yourself not to taste it,” says Winterer. “We are saying, ‘Let’s look at the letter in a different way.’”

Applying data mining to historical and literary subjects is not without detractors. Stephen Marche, a novelist and cultural critic, says the approach is misguided. “Trying to avoid the humanity of the work strikes me as pure folly,” he says. “How do you tag Franklin’s aphorisms? The engineering value is negligible; the human value is incalculable.” Other critics suggest the methods yield impressive-looking results without much meaning—“answers without questions.”

Winterer acknowledges the limits. “Digital humanities is a new starting point, never an endpoint,” she says. “For my project specifically, the digitization of early modern social networks can help us begin to discern new patterns and make new comparisons that would either not have occurred to us before or that would have been impossible to see, given the huge and fragmentary nature of the data set.”

To conduct the Franklin study, which Winterer began in 2008, existing computer-based mapping systems proved unsuitable for data gleaned from Enlightenment correspondence. “We had to create our own tools to focus on a visual language for handling humanities questions,” says Nicole Coleman, technology specialist at the Stanford Humanities Center.

***

The Republic of Letters was a community of the learned united by the exchange of correspondence, books and journals in pursuit of knowledge with little regard for religious, political and social boundaries. Serious correspondence was its lifeblood.

Gaining a foothold in the Republic’s social networks was vital for the acceptance of colonial American science, and required effort. The slow pace of trans-Atlantic mail and danger that items would fail to arrive necessitated a high level of organization. Moreover, correspondents often had to search out sympathetic sea captains to ensure that letters reached their destination, and rush to complete letters before vessels set sail—a practice detected and codified by Winterer’s tracking system, showing clusters of Franklin’s correspondence concentrated around ship-departure dates.

Winterer will analyze a more extensive network in the future, when she turns to Franklin’s post-1775 correspondence. After the American Revolution erupted, Franklin spent nine years in France as the representative of the fledgling United States. He would function as a central node in the Enlightenment intellectual networks on both sides of the Atlantic. By then, Winterer notes, he had become the Franklin we recognize—“the most famous American in the world, whose face by his own reckoning was as famous as the man in the moon.”

The impact of Winterer’s new take on Franklin in the world of ideas, like any emerging technology, can’t necessarily be predicted. That is perhaps fitting. Benjamin Franklin, inventor extraordinaire, wondered what the future would hold as he confronted the French fascination with the latest technological breakthrough, the lighter-than-air balloon. Asked his opinion of the new invention, Franklin shot back, “What is the good of a newborn baby?” Or so the story goes.