Your Guide to the Three Weeks of 1814 That We Today Call the War of 1812

From the burning of Washington to the siege of Baltimore, what happened in those late summer days?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/6e/286ee055-8bdb-4812-89a1-cf5403362dbd/e2246edit.jpg)

Despite its name, the War of 1812, at least in America, was barely fought in that year. Events in 1813 weren’t that noteworthy either. But in the late summer of 1814, the most famous events of the war, apart from the legendary Battle of New Orleans, occurred in a condensed period of just a few short weeks. The 200th anniversary of those events begins in just a few short days. Here’s the blow-by-blow of what happened, written by Peter Snow, author of the newly released history, “When Britain Burned the White House.”

August 24, 1814 – Midday – Bladensburg, Maryland

An army of 4,500 British redcoats suddenly appears at Bladensburg on the eastern bank of what is today known as the Anacostia River. They're battle-hardened veterans who have crushed the armies of the French emperor Napoleon in Europe. Robert Ross is their general, spurred on by the fiery Admiral George Cockburn who has been ravaging the Chesapeake for the past year.

Their mission: to give America and its President James Madison "a good drubbing" for declaring war on Britain two years earlier.

Their target: Washington, the newly built U.S. capital, in revenge for the sacking of York (the future Toronto) in 1813 when U.S. forces burned down Upper Canada's capital. But first the British must scatter the American force drawn up in three lines on the west bank of the river. And that's exactly what happens. The British cross and the battle of Bladensburg begins. The Americans, mainly poorly trained militia, led by a dithering and incompetent commander, Brig Gen William Winder, collapse before the relentless tramp of the British veterans. "We made a fine scamper of it," says one young Baltimore militiaman. Only the bravery of naval commodore Joshua Barney and his men in the third American line saves the U.S. from suffering one of the most shameful defeats in its young history. But they too are overwhelmed and by late afternoon the road to Washington is wide open.

August 24, 1814 – 8 p.m. – Washington, D.C.

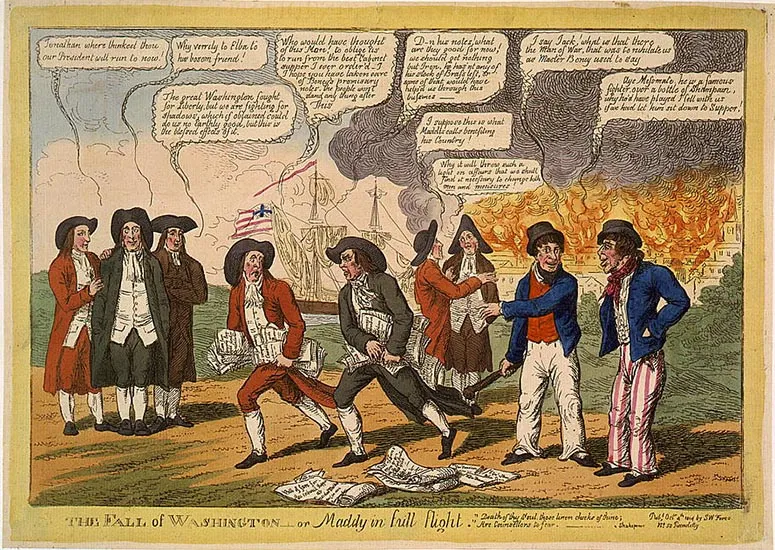

The British army strolls into an abandoned city. Madison's army has evaporated. The President has escaped across the Potomac to Virginia. His wife, the feisty Dolley Madison famously refuses to leave the White House until she's supervised the removal of George Washington's portrait from the wall of the dining room. In their hurry to depart, she and the White House servants leave the dinner table set for the President and his guests.

9 p.m.

Ross and Cockburn are fired upon as they approach the capital. Ross's horse is killed. What follows is a series of spectacular acts of destruction that will sharply divide opinion in the civilized world and even among Ross's own staff. First, the two commanders order the torching of both houses of Congress. The lavishly furnished Capitol designed in the proudest Classical style and completed by English-born architect Henry Latrobe, is soon engulfed in flames. Thousands of precious volumes in the Library of Congress are destroyed. An English member of Parliament will later accuse Ross and Cockburn of doing what even the Goths failed to do at Rome.

10 p.m.

The British find the White House empty. The tempting smell of freshly cooked food soon has them sitting at the Madison's table. They help themselves to the meat roasting in the spits and James Madison's favourite Madeira wine on the sideboard. It tastes "like nectar to the palates of the Gods," observes the delighted James Scott, Cockburn's chief aide. After the meal Scott helps himself to one of Madison's freshly laundered shirts in the bedroom upstairs. Cockburn and Ross then give the order to put the chairs on the table and set fire to the place. Within minutes, locals huddling in Georgetown and beyond witness the humiliating sight of their President's house ablaze. One of Ross's leading staff officers says he will "never forget the majesty of the flames", but confides that he believes the British action is "barbaric."

August 25 – Morning – Washington, D.C.

The British continue to burn the public buildings of Washington with the destruction of the Treasury, the State Department and the Department of War. Only the bravery of the Patent Office Director, William Thornton, who rides into the city and persuades the British invaders not to behave "like the Turks in Alexandria", saves the Patent Office from going up in flames too. A huge rainstorm drenches the burning buildings and leaves most of the walls standing although the interiors are gutted. Later in the day, Ross decides he has done enough damage and pulls his army out.

August 29 through September 2 – Alexandria, Virginia

It's the climax of one of the most audacious naval operations of all time. A flotilla of British frigates and other ships, sent up the Potomac to distract the Americans from the army's advance on Washington, manages to navigate the river's formidable shallows and anchor in a line with its guns threatening the prosperous town of Alexandria, Virginia. The townspeople, completely unprotected and appalled at the fate of Washington a few miles upriver, immediately offer to surrender. The British terms, delivered by Captain James Alexander Gordon who threatens to open fire if his conditions are not met, are harsh. The town's huge stocks of tobacco, cotton and flour are to be loaded onto no fewer than 21 American vessels and shipped down the Potomac to the British fleet in Chesapeake Bay. Alexandria's leaders agree to the terms. They will come under scathing criticism from their compatriots.

September 2 through September 11 – The Chesapeake Bay

The British army withdraws to its ships in the lower Chesapeake. The urging of some officers, including George Cockburn, fail to persuade General Ross to proceed immediately to attack the much larger and wealthier city of Baltimore, just a two-days march to the northeast. This respite allows Baltimore's redoubtable military commander, the resourceful Major General Sam Smith, to supervise prompt arrangements for the city's defense. He galvanizes Baltimore's population into digging trenches, building ramparts in response to his cry that Baltimore must not be allowed to suffer the fate of Washington. A massive flag, specially made by Baltimore seamstress Mary Pickersgill, is hoisted over Font McHenry to inspire its garrison to defend the entrance to Baltimore harbor.

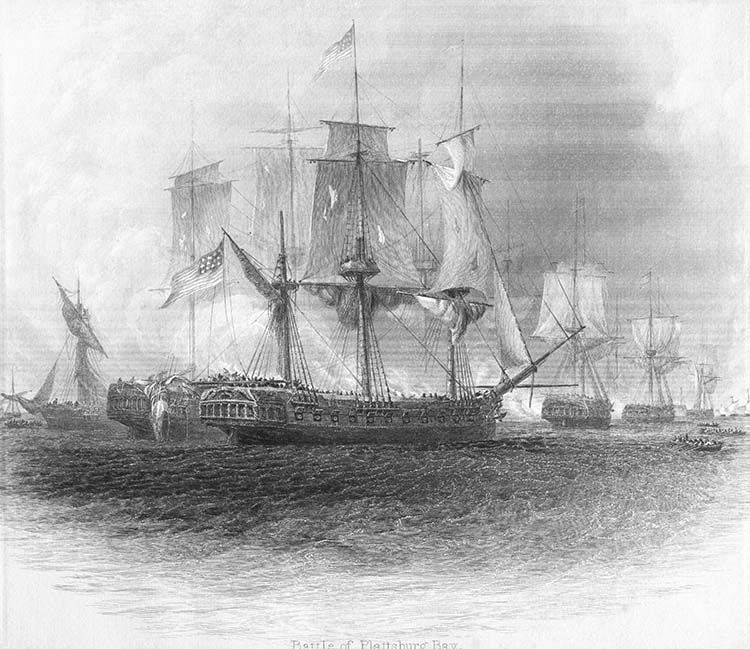

September 11 – Plattsburg, NY

While Ross finally decides to make an attack on Baltimore, a British army 500 miles to the north under General Prevost suffers a disastrous reverse at the town of Plattsburg. Prevost holds off his land attack on the town in anticipation of a victory by the British navy in the waters of the neighboring lake. But the British ships are defeated by American frigates maneuvering skillfully on their anchors, and Prevost aborts his campaign. The news of Plattsburg lifts morale in the States after the humiliation of Washington.

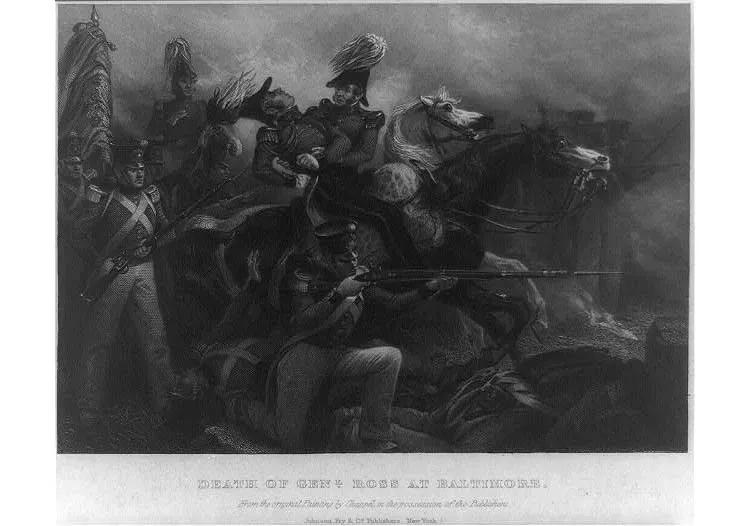

September 12 – The Battle of North Point

The British land at the foot of the North Point peninsula and Ross boasts he will eat supper in Baltimore. Within two hours, British fortunes are dramatically reversed when Ross, at the head of his advancing troops, is mortally wounded by an American rifleman. Another Irishman, Colonel Arthur Brooke, takes over and is immediately confronted by an American force dispatched by General Smith to delay the British advance. The Americans resist for a time but British numbers and rigid discipline soon force their enemy into what the British call a rout and the Americans insist is a fighting withdrawal. Brooke and Cockburn plan to make a night attack on Baltimore.

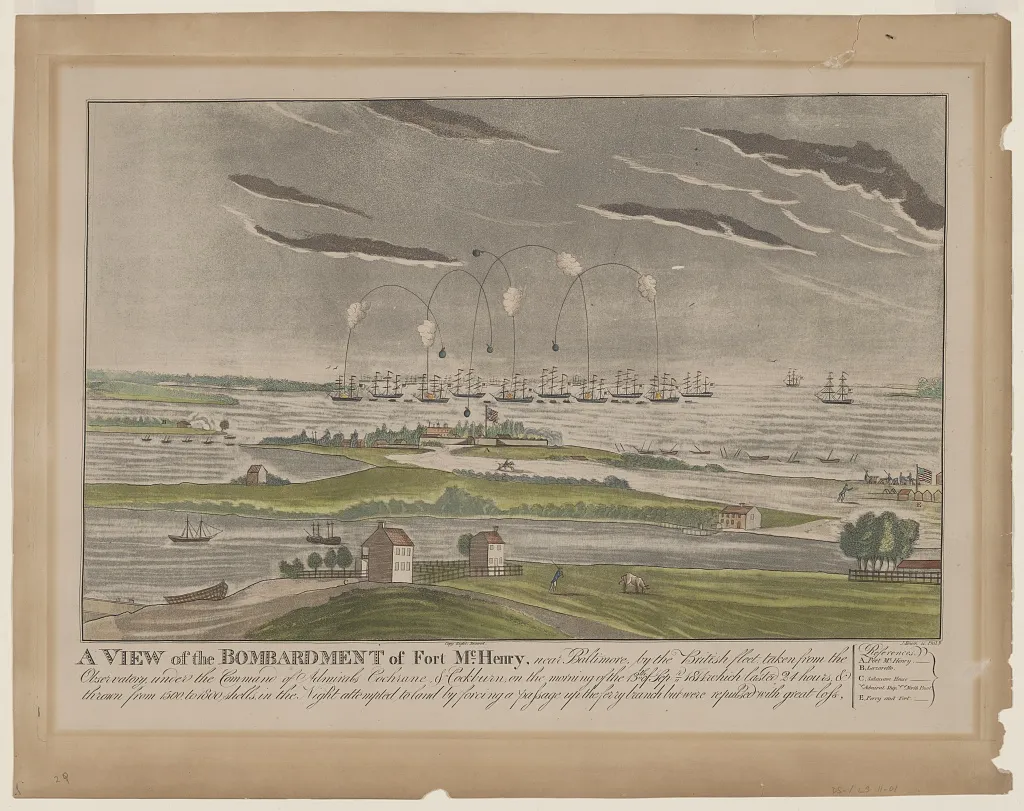

September 13-14 – Baltimore Harbor

While Brooke advances, several shallow draft British frigates and gunboats mount a massive bombardment of Fort McHenry in order to force entry to Baltimore's inner harbor. They fire rockets, mortar shells and ships' cannon balls at the fort. The intensity of the British fire prompts many townsfolk to abandon their homes convinced that the fort and the city must fall.

But the persistent British naval fire does not cause major damage or casualties. The British naval commander in chief sends a message to Brooke that further fighting will be fruitless and cost too many British lives.

September 14 - Baltimore

The siege of Baltimore is lifted. The British army retires to its ships, and the bombardment of Fort McHenry ceases. A young American poet and lawyer, Francis Scott Key, who has been watching the bombardment from a nearby vessel almost despairs of the fort's survival. But as he strains his eyes through the morning mist, he is astonished and delighted to see Mary Pickersgill’s flag still flying over the battlements. He takes a sheet of paper from his pocket and writes a poem that will earn him immortality: "O say can you see by the dawn's early light what so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming?" As the British fleet sails off down the Chesapeake, one crewman looks back at the great banner flying defiantly over the fort and writes in his diary "it was a galling sight for British seamen to behold."