Where Dinosaurs Roamed

Footprints at one of the nation’s oldest—and most fought over—fossil beds offer new clues to how the behemoths lived

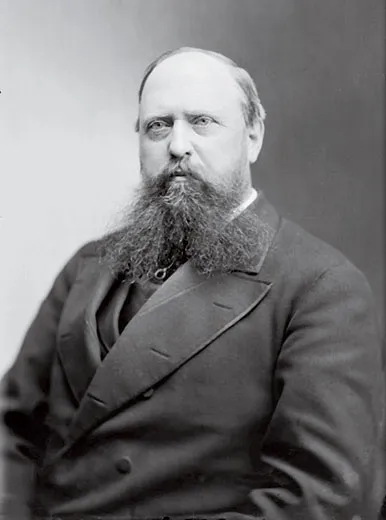

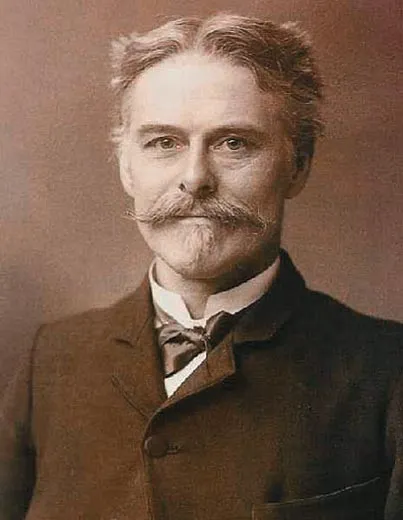

Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope were the two most prominent dinosaur specialists of the 1800s—and bitter enemies. They burned through money, funding expeditions to Western badlands, hiring bone collectors away from each other and bidding against one another for fossils in a battle of one-upmanship. They spied on each other's digs, had their minions smash fossils so the other couldn't collect them, and attacked each other in academic journals and across the pages of the New York Herald—making accusations of theft and plagiarism that tarnished them both. Yet between them they named more than 1,500 new species of fossil animals. They made Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus and Triceratops household names and sparked a dinomania that thrives today.

One of Marsh and Cope's skirmishes involved fossil beds in Morrison, Colorado, discovered in 1877 by Arthur Lakes, a teacher and geologist-for-hire. Lakes wrote in his journal that he had discovered bones "so monstrous...so utterly beyond anything I had ever read or conceived possible." He wrote to Marsh, at Yale, to offer his finds and services, but his letters met with vague replies and then silence. Lakes then sent some sample bones to Cope, the editor of American Naturalist. When Marsh got word that his rival was interested, he promptly hired Lakes. Under Marsh's control, the Morrison quarries yielded the world's first fossils of Stegosaurus and Apatosaurus, the long-necked plant eater more popularly known as Brontosaurus.

Lakes spent four field seasons chiseling the most easily reached bones out of the fossil beds. Before he left the area, he allegedly blew up one of the most productive sites—"Quarry 10"—to prevent Cope from digging there.

For 123 years, the site was lost, but in 2002 researchers from the Morrison Natural History Museum used Lakes' field notes, paintings and sketches to find the quarry, expose its original floor and support beams and begin digging once more. "The first things that we found were charcoal fragments: we were digging right below the campfire that Arthur Lakes had built," says Matthew Mossbrucker, director of the museum.

They quickly discovered that at least one misdeed attributed to the feud between Marsh and Cope was probably exaggerated. "It looks like [Lakes] just shoveled some dirt in there," says Mossbrucker. "I think he told people that he had dynamited it closed because he didn't want the competition up at the quarry—playing mind games with Cope's gang."

The reopened quarry is awash in overlooked fossils as well as relics that earlier paleontologists failed to recognize: dinosaur footprints that provide startling new clues about how the creatures lived.

The dig site is perched halfway up the west side of a narrow ridge called the Dakota hogback. The only way up is to walk—over loose rock, past prickly brush and rattlesnakes—with frequent pauses to catch one's breath. On this July morning, Mossbrucker leads six volunteers as they open the quarry for its fourth full modern-day field season. The crew erects a canopy over the pit before forming a bucket brigade to remove backfill that has washed into the hole since last season.

Down in a test pit, the crew digs into the side of the ridge, carefully undercutting the layer of cracked sandstone that served as the original quarry's ceiling. The ledge collapsed several times in the 1870s. More than 100 tons of rock crashed into the pit one night, and had the crew been working instead of sleeping nearby, Lakes wrote, the "entire party would have been crushed to atoms and buried beneath tons of rocks which afterwards took us over a week to remove by blasting and sledge hammers."

Robert Bakker, curator of paleontology for the Houston Museum of Natural Science, helps out at the dig. "If you want to understand the late Jurassic, you need to understand the common animals, which means Apatosaurus," he says. "This is the original Apatosaurus quarry, and it's a ‘triple-decker'—the only one in the world with three dead Apatosaurus buried one on top of each other."

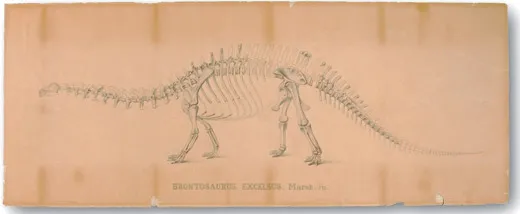

Most people know Apatosaurus as Brontosaurus because of a mistake made by Marsh. In 1879, two years after he named the first Apatosaurus, one of his workers discovered a more complete specimen in Wyoming. Marsh mistook it to be a new animal and named it Brontosaurus. Though the error was soon discovered, scientific nomenclature required keeping the first name. But in the meantime the "Brontosaurus" misnomer had made its way into popular culture.

For almost 100 years, Apatosaurus was portrayed as a swamp-bound animal whose immense body was buoyed by water. In the 1960s, Bakker joined a handful of paleontologists who argued that the massive beasts were really more like elephants: all-terrain animals that could roam over the flood plain, through river channels and anywhere else they wanted to go.

Bakker, then an undergraduate at Yale, went to Morrison to see if Apatosaurus' habitat supported his idea that the beasts were mobile. But he and two students spent two years unsuccessfully hunting for Quarry 10, which aside from being partially filled in, as Bakker finally discovered, was also obscured by bullet cartridges, beer cans and other remnants of teenage outings.

Today, Bakker is sifting through Lakes' spoil pile—lumps of clay stone that the 1870s crew tossed aside—when someone in the pit excitedly calls for him. He scrambles down into the hole, where his bearded face lights up under his straw cowboy hat. The museum crew has uncovered what appear to be Jurassic-era castings of a small tree's root system. "This is a big deal," says Bakker, using a finely bristled brush to baste the knobby fossils with glue. "In ‘CSI' terms, that's the crime scene floor. Victim number one"—the Apatosaurus found in 1877—"lay buried just above."

The clue adds to evidence that Apatosaurus did not live in water. The team has found layers of sediment consistent with a small pond, but none of the crocodile or tortoise fossils typically found in swamps from the Jurassic Period more than 200 million years ago. This spot may have attracted generations of Apatosaurus, Bakker says, because it provided a watering hole on a dry wooded plain. "If there was a forest, there would be a lot more wood—and there isn't—and a lot more fossilized leaves—and there ain't. So it was a woodland but probably a lot like Uganda—hot tropical woodland that was dry for most of the year."

The most significant recent discoveries at the Morrison quarries have been dinosaur tracks. Early dinosaur hunters overlooked them. In Quarry 10 and another Lakes quarry less than a mile away, museum staff have recovered 16 Stegosaurus tracks. They include ten hatchling tracks—the first ever discovered. One rock appears to show four or five baby Stegosauri all heading in the same direction. Another boulder includes a partial juvenile Stegosaurus hind paw track that was stepped on by an adult Stegosaurus. "It suggests that Stegosaurus moved in multiple-age herds," says Mossbrucker, and adults may have cared for hatchlings.

The researchers have also found the world's first baby Apatosaurus tracks. They could change paleontologists' view yet again: the tracks are from the rear legs only, and they are spaced far apart. "What's really cool about these tracks is that the baby animal is functionally running—but it's doing this just on its back legs. We had no idea a Bronto could run, let alone scoot along on its hind legs like a basilisk," Mossbrucker says, referring to the "Jesus lizard" that appears to walk on water.

He and others speculate that adult Apatosauri, some of the largest animals ever to walk the earth, could prop themselves up on two legs with the help of their long tails. But others argue that it would have been physiologically impossible to pump blood up the animals' long necks or to raise their heavy front limbs off the ground.

Bakker and Mossbrucker say their goal is to look at Quarry 10 holistically—considering the local geography, climate, flora and fauna—to create a picture of where and how Jurassic dinosaurs lived. "I want to know as completely as I can what kind of forgotten world these dinosaurs knew," says Mossbrucker. "I want to see what they saw, touch their earth with my own feet and be in the Jurassic."

Bakker gestures toward the pit, where Libby Prueher, the museum's curator of geology, sifts soil alongside volunteer Logan Thomas, a high-school student with a passion for snakes. "It's weird that [Marsh and Cope] thought that dinosaurs were a zero-sum game, that Marsh thought, ‘If Cope got a bone, I lost a bone,'" says Bakker. The goal isn't to vanquish one's rivals, he says: "the guiding inspiration for studying the dead dinosaurs is to get back to how they lived."

Genevieve Rajewski, a Boston-based writer, caught dinomania as a child and is surprised by how much paleontology has changed.