When Portugal Ruled the Seas

The country’s global adventurism in the 16th century linked continents and cultures as never before, as a new exhibition makes clear

Globalization began, you might say, a bit before the turn of the 16th century, in Portugal. At least that's the conclusion one is likely to reach after visiting a vast exhibition, more than four years in the making, at the Smithsonian's Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. The show, like the nation that is its subject, has brought together art and ideas from nearly all parts of the world.

It was Portugal that kicked off what has come to be known as the Age of Discovery, in the mid-1400s. The westernmost country in Europe, Portugal was the first to significantly probe the Atlantic Ocean, colonizing the Azores and other nearby islands, then braving the west coast of Africa. In 1488, Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias was the first to sail around the southern tip of Africa, and in 1498 his countryman Vasco da Gama repeated the experiment, making it as far as India. Portugal would establish ports as far west as Brazil, as far east as Japan, and along the coasts of Africa, India and China.

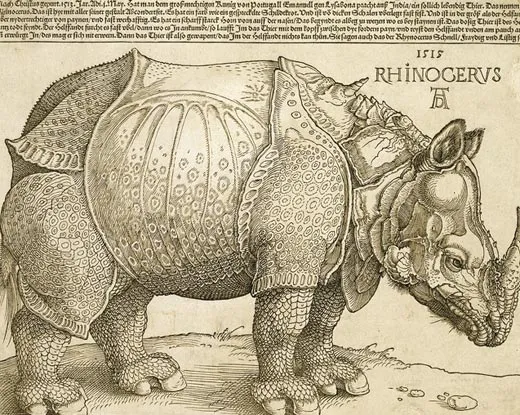

It was a "culturally exciting moment," says Jay Levenson of the Museum of Modern Art, guest curator of the exhibition. "All these cultures that had been separated by huge expanses of sea suddenly had a mechanism of learning about each other."

The exhibition, "Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the 16th & 17th Centuries," is the Sackler's largest to date, with some 250 objects from more than 100 lenders occupying the entire museum and spilling over into the neighboring National Museum of African Art. In a room full of maps, the first world map presented (from the early 1490s) is way off the mark (with an imaginary land bridge from southern Africa to Asia), but as subsequent efforts reflect the discoveries of Portuguese navigators, the continents morph into the shapes we recognize today.

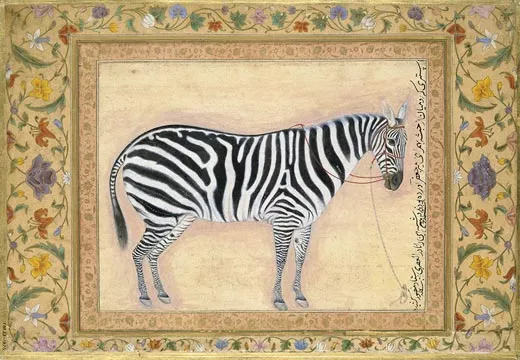

Another room is largely devoted to the kinds of objects that made their way into a Kunstkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, in which a wealthy European would display exotica fashioned out of materials from distant lands—ostrich shell drinking cups, tortoiseshell dishes, mother-of-pearl caskets. Each object, be it an African copper bracelet that made its way to a European collection or Flemish paintings of Portugal's fleet, points to Portugal's global influence.

It would be a serious error to think that Portugal's global ambitions were purely benevolent, or even economic, says UCLA historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam: "The Portuguese drive was not simply to explore and trade. It was also to deploy maritime violence, which they knew they were good at, in order to tax and subvert the trade of others, and to build a political structure, whether you want to call it an empire or not, overseas." Indeed, the exhibition catalog offers troubling reminders of misdeeds and even atrocities committed in Portugal's name: the boatful of Muslims set ablaze by the ruthless Vasco da Gama, the African slaves imported to fuel Brazil's economy.

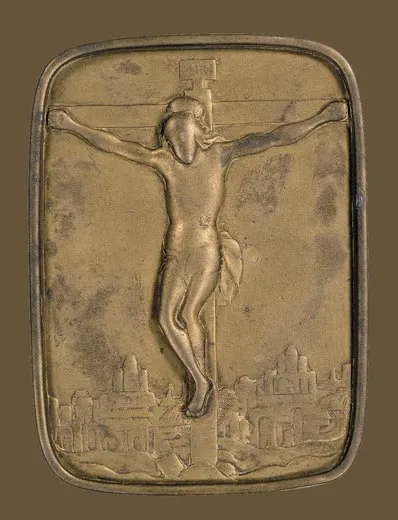

When different cultures have encountered each other for the first time, there has often been misunderstanding, bigotry, even hostility, and the Portuguese were not alone in this regard. The Japanese called the Portuguese who landed on their shores "Southern Barbarians" (since they arrived mostly from the south). Some of the most intriguing objects in the exhibit are brass medallions depicting the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Not long after Portuguese missionaries converted many Japanese to Christianity, Japanese military rulers began persecuting the converts, forcing them to tread on these fumi-e ("pictures to step on") to show they had renounced the barbarians' religion.

With such cultural tensions on display in often exquisite works of art, "Encompassing the Globe" has been a critical favorite. The New York Times called it a "tour de force," and the Washington Post found the exhibition "fascinating" in its depiction of "the tense, difficult and sometimes brutal birth of the modern world." The exhibition closes September 16, and opens October 27 at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Brussels, a seat of the European Union, now headed by Portugal.

The president of Portugal, Aníbal Cavaco Silva, declares in a forward to the exhibition catalog, "The routes that the Portuguese created to connect the continents and oceans are the foundation of the world we inhabit today." For better or worse, one is tempted to add.

Former intern David Zaz is a fellow at Moment Magazine.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)