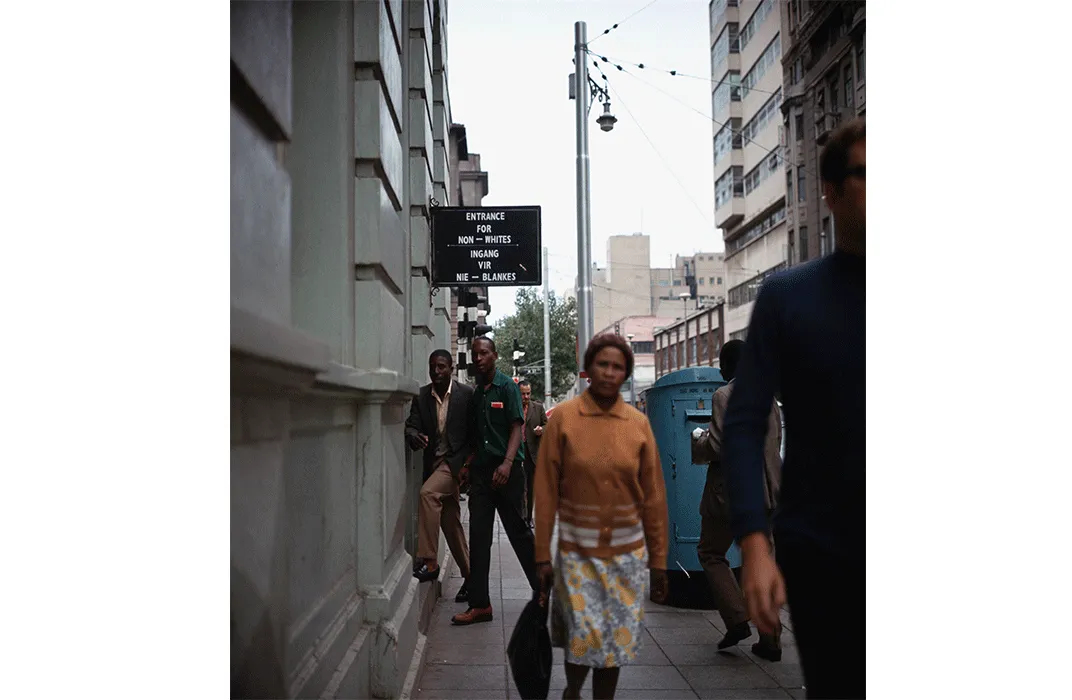

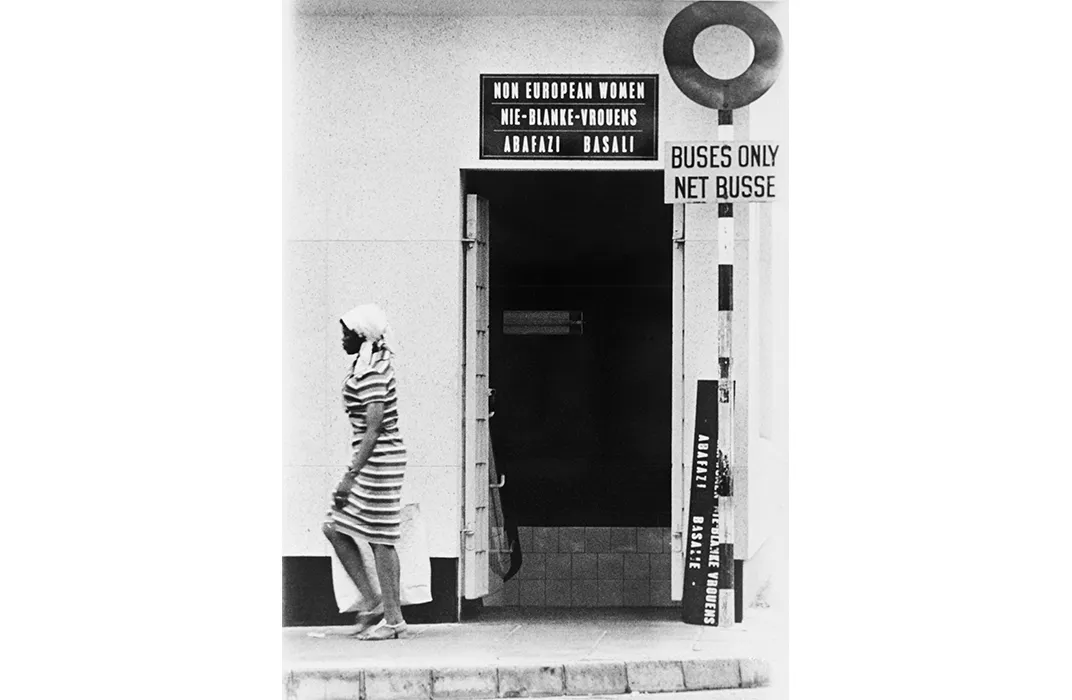

A Look Back at South Africa Under Apartheid, Twenty-Five Years After Its Repeal

Segregated public facilities, including beaches, were commonplace, but even today, the inequality persists

The year 1990 signaled a new era for apartheid South Africa: Nelson Mandela was released from prison, President F.W. de Klerk lifted the ban on Mandela's political party, the African National Congress, and Parliament repealed the law that legalized apartheid.

There are few words more closely associated with 20th-century South African history than apartheid, the Afrikaan word for "apartness" that describes the nation's official system of racial segregation. And though the discriminatory divide between whites of European descent and black Africans stretch back to the era of 19th-century British and Dutch imperialism, the concept of apartheid did not become law until 1953, when the white-dominated parliament passed the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, which officially segregated public spaces such as taxis, ambulances, hearses, buses, trains, elevators, benches, bathrooms, parks, church halls, town halls, cinemas, theaters, cafes, restaurants, hotels, schools, universities—and later, with an amendment, beaches and the seashore.

But the repeal was more symbolic than activating because the intended result was already in motion, says Daniel Magaziner, associate professor of history at Yale University and author of The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968-1977. By the time of the repeal, South Africans had already begun to ignore some of the legal separation of the races in public spaces. For instance, blacks were supposed to yield the sidewalk to whites, but in large cities like Johannesburg, that social norm had long since passed. And in many places total racial segregation was impossible; these were places like whites-only parks, where blacks were the maintenance crew and black nannies took white children to play.

“The fact that the repeal was passed so overwhelmingly by Parliament, I don’t think speaks to the sudden liberalization of South African politics,” says Magaziner. “I think it speaks to people recognizing the reality that this was a law that was anachronistic and wasn’t in practical effect anymore.”

The impact of apartheid, however, was nowhere near over when the repeal went into effect on October 15, 1990. While white South Africans only made up 10 percent of the country’s population at the end of apartheid, they owned nearly 90 percent of the land. In the quarter-century since the act's repeal, land distribution remains a point of inequality in the country. Despite the post-apartheid government's stated plan to redistribute one-third of the country's land from whites to blacks by 2014, less than 10 percent of this land has been redistributed, and the 2014 deadline has been postponed to 2025.

Magaziner cautions that focusing on the repeal of the Separate Amenities Act as a sign of the end of apartheid obscures the deeper problems caused by racial segregation that continue to impact the country today.

“The Separate Amenities Act made visible what had been longstanding practices,” says Magaziner, “but it also made invisible other aspects of segregation that weren’t covered by the Act but have a much longer lasting impact in South Africa.”

The photos above, selected from the photo archives of the United Nations and Corbis, show the impact of the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act in public spaces in South Africa.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)