UPDATE: The Reaction to Karen King’s Gospel Discovery

When a divinity scholar unveiled a papyrus fragment that she says refers to Jesus’ “wife,” our reporter was there in Rome amidst the firestorm of criticism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Gospels-Crucifixion-631.jpg)

Editor's Note: In June 2016, reporter Ariel Sabar investigated the origins of the "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" for the Atlantic magazine. In response to Sabar's findings about the artifact's provenance, Harvard University scholar Karen King stated that the new information "tips the balance towards [the papryus being a] forgery."

Read the article that launched the controversy below.

This story is an update of the news broken by Smithsonian magazine on September 18, 2012.

Up a cobblestone driveway in the heart of Rome, across from the soaring Tuscan columns of St. Peter’s Square, juts a narrow building watched over by a heavy-lidded statue of Saint Augustine. The Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum was founded in 1970, in the shadow of the Vatican, to renew the teachings of Church fathers. On most days, its glinting marble halls echo with the footsteps of theology students immersing themselves in doctrine, canon law and sacred Scripture.

On September 18, however, the building played host to a secular gathering that some would soon see as profane: the International Congress of Coptic Studies, a quadrennial academic conference that this year drew more than 300 scholaars from 27 countries.

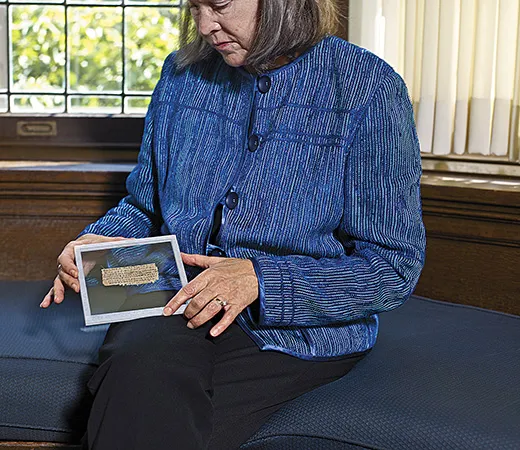

Karen L. King, who is Harvard’s Hollis professor of divinity, one of the most rarefied perches in religious studies, had spent months preparing her paper. Its humdrum title in the conference program—“A New Coptic Gospel Fragment”—gave no hint of the jolts it would soon send through the Christian world.

A few minutes before 7 p.m., I took my seat along with nearly three dozen scholars in a fourth-floor classroom adorned with faded maps of the Roman Empire. The air outside was balmy and clear, and through the windows the sun dipped toward the great dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. King, wearing rimless oval glasses, loose black slacks and a white blouse, her gray-streaked hair held in place with bobby pins, got up from a seat beside her husband and strode to the raised desk at the front of the room. A plain wooden crucifix hung on the wall behind her.

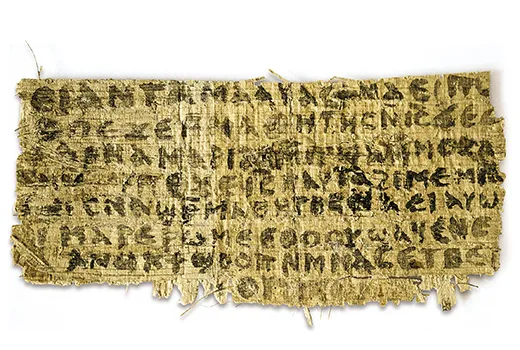

With just half an hour to speak, she wasted no time: She had come upon an ancient scrap of papyrus on which a scribe had written the words, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife . . . ’”

“She will be able to be my disciple,” says the next line. Then, two lines later: “I dwell with her.”

The words on the fragment, scattered across 14 incomplete lines, leave a good deal to interpretation. But in King’s analysis, the “wife” Jesus refers to is probably Mary Magdalene, and Jesus appears to be defending her against someone, perhaps one of the male disciples.

The papyrus was a stunner: the first and only known text from antiquity to depict a married Jesus.

The writing was in the ancient Egyptian language of Coptic, into which many early Christian texts were translated in the third and fourth centuries, when Alexandria vied with Rome as an incubator of Christian thought. But King made no claim for its usefulness as biography, saying instead the text was probably composed in Greek a century or so after the Crucifixion, then copied into Coptic two centuries later. As evidence that the real-life Jesus was married, it is scarcely more dispositive than Dan Brown’s controversial 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code.

What it does seem to reveal is more subtle and complex: that some group of early Christians drew spiritual strength from portraying the man whose teachings they followed as being married. All of this assumes, however, that the fragment is genuine, a question that as of press time was far from settled. That her announcement would be taken in part as a provocation was clear from the name she’d given the text: “The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.”

King had planned to project images of the papyrus onto the classroom wall, but her laptop—with her paper and PowerPoint presentation—went on the fritz on the transatlantic flight. She’d reconstructed her lecture notes largely from memory, and now directed her audience to a Harvard website where the images were posted. The fragment itself was locked up at the Harvard Divinity School library.

“Even a tiny fragment of papyrus,” she said in closing, “can offer surprises with the potential to significantly enrich our historical reconstruction of the range of ancient Christian theological imagination and practice. I await very eagerly your response.”

The room erupted in applause. Einar Thomassen, a religious historian at the University of Bergen, in Norway, stood up. “Thank you, Karen, this is truly sensational,” he said.

At almost the precise moment King began her talk, Harvard issued a press release, launching news reports and commentary around the world. Theologians clashed over the discovery’s significance. Twitter gave birth to the hashtag #jesuswife. The comic Stephen Colbert, a devout Catholic, worried, in jest, whether confession would remain confidential: “You know he’s going to tell her. You can’t have secrets in a marriage.” A Vatican spokesman said “this little scrap of parchment...does not change anything in the position of the Church, which rests on an enormous tradition” of Jesus’ celibacy. (A week later the Vatican newspaper would denounce the papyrus as a “fake.”)

The next day at the Coptic studies conference, the early enthusiasm turned sour. Scholars had by then examined images of the fragment, and several told me that its size, handwriting and grammar left them with serious doubts about its authenticity. Even King’s interpretation was called into question.

“Some guy in the first or second century decided to write the words ‘my wife’ and put them in Jesus’ mouth,” Wolf-Peter Funk, a professor at Laval University in Quebec and an authority on early Christian manuscripts, told me while taking a smoking break on the institute’s front steps. “There’s no evidence it’s any real gospel text or literary manuscript, and that’s all there is to be said.”

By that afternoon, so many European journalists had shown up that the conference organizer threw together an impromptu press conference. King walked in as a CBS camera crew was setting up lights. A correspondent for the newspaper La Repubblica grilled King on her decision to make the announcement in the Eternal City. “That is sort of a symbol,” he said.

King replied that it was just chance that the conference was in Rome. “It has no larger symbolic meaning,” she said. Afterward, as the reporters packed their gear, a young priest in the hallway muttered “sciocchezzuole sciocco”—“silly foolishness.”

***

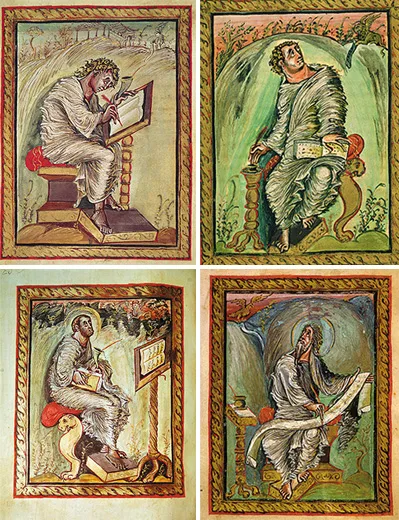

Harvard Divinity School’s Andover Hall overlooks a quiet street some 15 minutes by foot from the bustle of Harvard Square. A Gothic tower of gray stone rises from its center, its parapet engraved with the icons of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It was two weeks before the Rome announcement. (This magazine had learned of King’s find from Smithsonian Channel colleagues, who are preparing a documentary.) I found her office by scaling a narrow flight of stairs that appeared to lead to the roof but opened instead on a garret-like room in the highest reaches of the tower.

“So here it is,” King said.

On her desk, next to an open can of Diet Dr Pepper promoting the movie The Avengers, was the scrap of papyrus, pressed between two plates of plexiglass. The fragment was about the size of a business card, honey-hued and inked on both sides with faded black script. When she lifted the papyrus to her office’s arched window, sunlight seeped through where the reeds had worn thin. “It’s in pretty good shape,” she said. “I’m not going to look this good after 1,600 years.”

King, who is 58, had moved to Harvard from Occidental College in 1997 and found herself on a fast track. In 2009, the divinity school named her the Hollis professor—the oldest endowed chair in the United States and a 288-year-old post that had never before been held by a woman.

Her scholarship has been a kind of sustained critique of what she calls the “master story” of Christianity: a narrative that casts the New Testament as divine revelation that passed through Jesus in “an unbroken chain” to the apostles and their successors—church fathers, ministers, priests and bishops who carried its truths into the present day.

According to this “myth of origins,” as she has called it, followers of Jesus who accepted the New Testament canon—chiefly the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, written roughly between A.D. 65 and A.D. 95, or at least 35 years after Jesus’ death—were true Christians. Followers inspired by noncanonical gospels were heretics hornswoggled by the devil.

Until the last century, virtually everything scholars knew about these other gospels came from broadsides against them by early Church leaders. Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyon, France, pilloried them in A.D. 180 as “an abyss of madness and of blasphemy”—a “wicked art” practiced by people bent on “adapting the oracles of the Lord to their opinions.” (Many will no doubt view “The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” through the same prism.)

A challenge to Christianity’s master story surfaced in December 1945, when an Arab farmer digging near the town of Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, stumbled on a cache of manuscripts. Inside a meter-tall clay jar containing 13 leatherbound papyrus codices were 52 texts that didn’t make it into the canon, including the gospel of Thomas, the gospel of Philip and the Secret Revelation of John.

As scholars translated the texts from Coptic, early Christians whose views had fallen out of favor—or were silenced—began speaking again, across the ages, in their own voices. A picture began to take shape of long-ago Christians, scattered across the Eastern Mediterranean, who derived sometimes contradictory teachings from the life of Jesus Christ. Was it possible that Judas was not a turncoat but a favored disciple? Did Christ’s body really rise, or just his soul? Was the crucifixion—and human suffering, more broadly—a prerequisite for salvation?

Only later did an organized Church sort the answers to those questions into the categories of orthodoxy and heresy. (Some scholars prefer the term “Gnostic” to heretical; King rejects both, arguing in a 2003 book that “Gnosticism” is a construct “invented in the early modern period to aid in defining the boundaries of normative Christianity.”)

A mystery these newly discovered gospels touched on—and that came to preoccupy King—was Jesus’ relationship with Magdalene. The New Testament often lists her first among the women who followed and “provided for” Jesus. When the other disciples flee Christ on the cross, Magdalene stays by his side. She is at his burial and, in the Gospel of John, is the first person Jesus appears to after rising from the tomb. Thus she is the first to proclaim the “good news” of his resurrection—a role that later earns her the title “apostle to the apostles.”

The gospel of Philip, one of the Nag Hammadi texts, goes further, describing Magdalene as a “companion” of Jesus “whom the Savior loved more than all the other disciples and [whom] he kissed often on the mouth.” But whether these “kisses” were spiritual or symbolic or something more is left unstated.

The gospel of Mary, which surfaced in January 1896 on the Cairo antiquities market, casts Magdalene in a still more central role, as confidante and chief disciple. The text, King argues in her book The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle, is no less than a treatise on the qualifications for apostleship: What counted was not whether you were at the crucifixion or the resurrection, or whether you were a woman or a man. What counted was your firmness of character and how well you understood Jesus’ teachings.

The efforts of historians to reclaim the voices in these lost gospels have given fits to conservative scholars and believers, who view them as a perversion of long-settled truth by identity politics. “Far from being the alternative voices of Jesus’ first followers, most of the lost gospels should rather be seen as the writings of much later dissidents who broke away from an already established orthodox church,” Philip Jenkins, a historian at Baylor University, writes in his book Hidden Gospels: How the Search for Jesus Lost Its Way. “Despite its dubious sources and controversial methods, the new Jesus scholarship... gained such a following because it told a lay audience what it wanted to hear.”

Writing on Beliefnet.com in 2003, Kenneth L. Woodward, Newsweek’s longtime religion editor, argued that “Mary Magdalene has become a project for a certain kind of ideologically committed feminist scholarship.” He added that “a small group of well-educated women decided to devote their careers to the pieces of Gnostic literature discovered in the last century, a find that promised a new academic specialty within the somewhat overtrodden field of Biblical studies.”

In a reply posted to Beliefnet, King called Woodward’s piece “more an expression of Woodward’s distaste for feminism than a review or even a critique of [the] scholarship.”

“You don’t walk over her,” one of King’s former graduate students said.

***

On July 9, 2010, during summer break, an e-mail from a stranger arrived in King’s in-box. Because of her prominence, she gets a steady trickle of what she calls “kooky” e-mails: a woman claiming to be Mary Magdalene, a man with a code unlocking the mysteries of the Bible.

This one looked more serious. The writer identified himself as a manuscript collector. He said he had acquired a Gnostic gospel that appeared to contain an “argument” between Jesus and a disciple about Magdalene. Would she take a look at some photographs?

King asked for more information: What was its date and provenance? The man replied that he purchased it in 1997 from a Berliner who had obtained it in Communist East Germany in the 1960s and later immigrated to the United States. (In a later e-mail, however, the story seemed to change slightly, with the collector saying that the papyri had been in the previous owner’s possession—or his family’s—“prior to WWII.”) The collector sent an electronic file of photographs and an unsigned translation with the bombshell phrase about Jesus’ wife.

“My reaction is, This is highly likely to be a forgery,” King recalled of her first impressions. “That’s kind of what we have these days: Jesus’ tomb, James’ Ossuary.” She was referring to two recent “discoveries,” announced with great fanfare, that were later exposed as hoaxes or, at best, wishful thinking. “OK, Jesus married? I thought, Yeah, yeah, yeah.

“I was highly suspicious that the Harvard imprimatur was being asked to be put on something that then would be worth a lot of money,” she recalled. “I didn’t know who this individual was and I was busy working on other stuff, so I let it slide for quite a while.”

In late June 2011, nearly a year after their first exchange, the collector gave her a nudge. “My problem right now is this,” he wrote in an e-mail that King shared with me, after stripping out identifying details. (King has granted the man’s request for anonymity.) “A European manuscript dealer has offered a considerable amount for this fragment. It’s almost too good to be true.” The collector did not want the fragment to disappear in a private archive. “Before letting this happen, I would like to either donate it to a reputable manuscript collection or wait at least until it is published, before I sell it.”

Four months later, after making a closer study of the photographs, King replied. The text was intriguing, but she could not proceed on photographs alone. She would need more details about its history, and an expert papyrologist would have to examine it.

King brushed aside the collector’s offer to send it through the mail—“You don’t do that! You hardly want to send a letter in the mail!” So last December, he delivered it by hand.

“We signed the paperwork, had coffee and he left,” she said.

The collector knew nothing about the fragment’s origins. The paper trail, such as it was, stopped with the prior owner, one H. U. Laukamp.

Among the papers the collector had shown King was a typed July 1982 letter to Laukamp from Peter Munro, a prominent Egyptologist and former director of the Kestner Museum, in Hannover. Laukamp had apparently consulted Munro about a batch of papyri, and Munro wrote back that a colleague at Berlin’s Free University, Gerhard Fecht, an expert on Egyptian languages and texts, had identified one of the Coptic pieces as a second- to fourth-century A.D. fragment of the Gospel of John.

The current owner also left King an unsigned, undated handwritten note— concerning a different papyrus—that appears to belong to the same 1982 correspondence. “Professor Fecht believes that the small fragment, approximately 8 cm in size, is the sole example of a text in which Jesus uses direct speech with reference to having a wife. Fecht is of the opinion that this could be evidence for a possible marriage.”

I asked King why neither Fecht nor Munro sought to publish so tantalizing a discovery. “People interested in Egyptology tend not to be interested in Christianity,” she said. “They’re into Pharaonic stuff.” Also, manuscript dealers tend to worry most about financial value, and attitudes differ about whether publication helps or hinders.

But King could not ask. Laukamp died in 2001, Fecht in 2006 and Munro in 2008.

For legal purposes, the 1982 date of the correspondence was crucial, though it may well strike critics as suspiciously convenient. The next year, Egypt would revise its antiquities law to declare that all discoveries after 1983 were the unequivocal property of the Egyptian government.

Though King can read Coptic and has worked with papyri, she would need outside help to authenticate the fragment. She forwarded the photos to AnneMarie Luijendijk, an authority on Coptic papyri and sacred scriptures at Princeton. (King had overseen her dissertation at Harvard.)

Luijendijk took the images to Roger Bagnall, a renowned papyrologist who directs the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. Every few weeks, a group of papyrologists in the New York area gather at Bagnall’s Upper West Side apartment to vet new discoveries. Bagnall serves tea, coffee and cookies, and projects images of papyri under discussion onto a screen in his living room. After looking at images of the papyrus, “we were unanimous in believing, yes, this was OK,” Bagnall told me by phone.

It wasn’t until King brought the fragment by train to Bagnall’s office last March that he and Luijendijk reached a firm conclusion. The papyrus’ color and texture, along with the parallel deterioration of the ink and the reeds, were signs of authenticity. Also convincing was the scribe’s middling penmanship. “It’s clear the pen wasn’t perhaps of ideal quality and the writer didn’t have complete control of it,” said Bagnall. “The flow of ink was highly irregular. This wasn’t a high-class professional working with good tools. That is one of the things that tells you it’s real, because a modern scribe wouldn’t do that. You’d have to be really kind of perversely skilled to produce something like this as a fake.”

The Sahidic dialect of Coptic and the style of the handwriting, with letters whose tails do not stray above or below the line, reminded Luijendijk of texts from Nag Hammadi and elsewhere and helped her and Bagnall date the fragment to the second half of the fourth century A.D. and place its probable origins in Upper Egypt.

The fragment’s rough edges suggest that it had been cut from a larger manuscript; experts told me that some dealers, keener on profit than preservation, will dice up a text for maximum return. The presence of writing on both sides indicated it was part of a codex—or book—rather than a scroll.

In Luijendijk’s judgment, the scribe’s handwriting—functional, but not refined—suggests that this gospel was read not in a church, where more elegant calligraphy prevailed, but by early Christians who gathered in homes for private study. “Something like a Bible study group,” Luijendijk told me.

To help bring out letters whose ink had faded, King borrowed Bagnall’s infrared camera and used Photoshop to enhance the contrasts. The papyrus’ back side, or verso, is so badly damaged that only a few key words—“my mother” and “three”—were decipherable. But on the front side, or recto, King gleaned eight fragmentary lines:

1) “not [to] me. My mother gave to me li[fe]...”

2) The disciples said to Jesus, “

3) deny. Mary is worthy of it

4) ” Jesus said to them, “My wife

5) she will be able to be my disciple

6) Let wicked people swell up

7) As for me, I dwell with herin order to

8) an image

The line—“Jesus said to them, ‘My wife...’”—is truncated but unequivocal. But with so little surrounding text, what might it mean?

Some of the phrases echoed, if distantly, passages in Luke, Matthew and Thomas about the role of family in the life of disciples. The parallels convinced King that this gospel was first composed, most likely in Greek, in the second century A.D., when such questions were a subject of lively theological discussion. (The term “gospel,” as King uses it in her analysis, is any early Christian writing that describes the life—or afterlife—of Jesus.) Despite the New Testament’s many Marys, King infers from a variety of clues that the “Mary” in Line 3 is “probably” Magdalene, and that the “wife” in Line 4 and “she” in Line 5 is this same woman.

For King, the best historical evidence that Magdalene was not Jesus’ wife is that the New Testament (which is silent about his marital status) refers to her by her hometown, Migdal, a fishing village, rather than by her relationship to the Messiah. “The most odd thing in the world is her standing next to Jesus and the New Testament identifying her by the place she comes from instead of her husband,” King told me. In that time, “women’s status was determined by the men to whom they were attached.” Think of “Mary, Mother of Jesus, Wife of Joseph.”

The first known statements about Jesus’ celibacy appeared about a century after his death. Clement of Alexandria, a theologian and church father who lived from A.D. 150 to A.D. 215, reported on a group of second-century Christians “who say outright that marriage is fornication and teach that it was introduced by the devil. They proudly say that they are imitating the Lord who neither married or had any possession in this world, boasting that they understand the gospel better than anyone else.”

Clement himself took a less proscriptive view, writing that while celibacy and virginity were good for God’s elect, Christians could have sex in marriage so long as it was without desire and for procreation. Other church fathers also invoked Jesus’ unmarried state. Complete unmarriedness—innuptus in totum, as Tertullian puts it—was how a holy man turned away from the world, and toward God’s new kingdom.

What the papyrus fragment suggests, King said, “is that there were early Christians...who could understand indeed that sexual union in marriage could be an imitation of God’s creativity and generativity and it could be spiritually proper and appropriate.”

In a 52-page article submitted to the Harvard Theological Review, King speculates that the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” may have been tossed on some long-ago garbage heap not because the papyrus was worn or damaged, but “because the ideas it contained flowed so strongly against the ascetic currents of the tides in which Christian practices and understandings of marriage and sexual intercourse were surging.”

The Review, a quarterly, had planned to publish her article in its October issue. But in early September an editor informed her that a peer reviewer had sharply questioned the papyrus’ authenticity; grammatical irregularities and the ink’s appearance pointed, the reviewer wrote, to a forgery.

Shocked, King e-mailed the anonymous critique to Bagnall, Luijendijk and another expert, Ariel Shisha-Halevy, an eminent Coptic linguist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Shisha-Halevy replied, “I believe—on the basis of language and grammar—the text is authentic.”

All three felt confident enough for her to announce her finding in Rome, but they pressed her to revise her article and submit the fragment to a noninvasive test—like a multispectral analysis— to make sure the ink’s chemistry was compatible with inks from antiquity.

“I have zero interest in publishing anything that’s a forgery,” she told me over dinner in Cambridge before she left for Rome.

Would she need 100 percent confidence? I asked.

“One hundred percent doesn’t exist,” she said. “But 50-50 doesn’t cut it.”

***

King grew up in Sheridan, Montana, a cattle ranching town of 700 people an hour’s drive southeast of Butte. Her father was a pharmacist. Her mother took care of the children—King is the second of four—taught home economics at the high school and raised horses. For reasons Karen King still doesn’t quite understand—perhaps it was the birthmark on her face, perhaps her bookishness—she was picked on and bullied “from grade school on.” For many years, she went with her family to Sheridan’s Methodist Church. In high school, though, King switched, on her own, to the Episcopal Church, which she regarded as “more earnest.”

“The Methodists were doing ’70s things—Coca-Cola for the Eucharist,” she told me. “It wasn’t that I was terribly righteous. But...intellectually, the Episcopal Church was where the ideas were.”

I asked her what had first drawn her to the so-called “heretical” gospels. “I’ve always had a sense of not fitting in,” she said. “I thought, if I could figure out these texts, I could figure out what was wrong with me.”

Was she still a practicing Christian? Her faith, she said, had sustained her through a life-threatening, three-year bout with cancer that went into remission in 2008, after radiation treatment and seven surgeries. She said she attends services, irregularly, at an Episcopal Church near her home, in Arlington, a town northwest of Cambridge. “Religion is absolutely central to who I am in every way,” she said. “I spend most of my time on it. It’s how I structure my interior life. I use its materials when I think about ethics and politics.”

***

Among the many controversies barnacling King’s discovery is whether she went public too soon. In view of its explosive content, might it have been more responsible to wait for definitive word of its authenticity, legal status and provenance? The case of the last major Gnostic discovery offers no straightforward answer. In the early 2000s, the National Geographic Society assembled a team of experts to piece together nearly 1,000 scraps of papyrus into the first known copy of the “The Gospel of Judas,” a Gnostic text lost for some 17 centuries. Before making an announcement, the experts, who were sworn to secrecy, seemed to take every precaution: radiocarbon dating, ink tests, handwriting and content analyses.

When the society announced the find at an April 2006 news conference, it created a tidal wave of publicity: Its translation depicted Judas not as the traitor of lore, but as a hero who turns Jesus in at the Savior’s own bidding and who then ascends, as a reward, to heaven. But within a year, scholars identified significant problems with the translation that cast doubt on the society’s headline-grabbing portrayal. The innocuous-sounding word “spirit”—used to describe Judas—should instead have been translated as “demon,” and Judas was not set apart “for” the holy generation but “from” it—a world of difference. National Geographic disputed the criticism, then quietly published a revised translation. Some academics criticized the secrecy surrounding the project, saying that allowing outside scholars earlier access would have produced a more accurate—if perhaps less sensational—interpretation.

“The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife” may serve as a test case for that more open approach. As we descended the steps after her talk in Rome, I asked King about the alternative intepretations proposed by her colleagues during a short question and answer session. “This is exactly what we do,” she said, alluding to the argument and counterargument by which scholars grope toward truth. During her talk King had invited scholars to Harvard to examine the fragment firsthand. “This is the first word,” she said of her paper, “not the last word.”

But if scientific tests show that the text is a fake, the last word could come fast—and with scant forgiveness. “If it’s a forgery,” King told one newspaper, “it’s a career breaker.”

After flying back from Italy, I e-mailed Kevin J. Madigan, co-editor of the Harvard Theological Review and an associate dean at the divinity school. “Everything is now on hold until we are able, with Professor King’s help and by scientific dating, to establish the authenticity of the text,” he replied, saying the journal also was interested in “further verification from Coptological papyrologists and grammarians.”

As of late October, the results of a radiocarbon dating test and ink analysis were still pending.

I wanted to hear from Elaine Pagels, a Princeton professor who is one of the world’s foremost authorities on the Gnostic gospels. Pagels and King had worked together on a 2007 book about the gospel of Judas, and remain friends and colleagues. Pagels told me over the phone that she had little doubt about the authenticity of the papyrus King had studied, but Pagels wondered about the decision to call it a “gospel,” which to Pagels implies a text professing to chronicle real events in Jesus’ life. It could just as easily be a “dialogue text,” in which followers relate often symbolic visions from Jesus, or even what some commentators have called “fan fiction.”

“At least 99 percent of this text is missing,” Pagels told me. “Calling it a gospel, I’m sorry, I don’t understand that except to make it sound more, well—what’s the word?—important. It’s much more sensational than what we can infer.”

***

King makes no secret of her contrarian approach to Christian history. “You’re talking to someone who’s trying to integrate a whole set of ‘heretical’ literature into the standard history,” she said in our first phone conversation, noting later that “heretical” was a term she does not accept.

But what was she after, exactly? Was her goal to make Christianity a bigger tent? Was it to make clergy more tolerant of difference?

“I’m less interested in proselytizing or a bigger tent for its own sake than in issues of human flourishing,” she said. “It’s more the, How do we get along? What does it mean for living now?

“What history can do,” she said, “is show that people have to take responsibility for what they activate out of their tradition. It’s not just a given thing one slavishly follows. You have to be accountable.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)