Treasures Trove

America’s most singular sensations are at the National Air and Space Museum

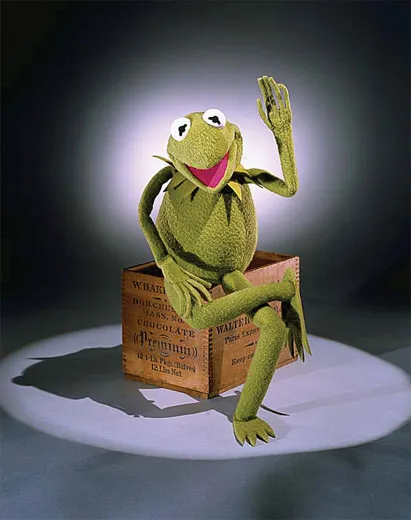

For the only time in history, the top hat Abraham Lincoln wore the night he was assassinated is within a few feet of Kermit the Frog, and just down the hall from SpaceShipOne.

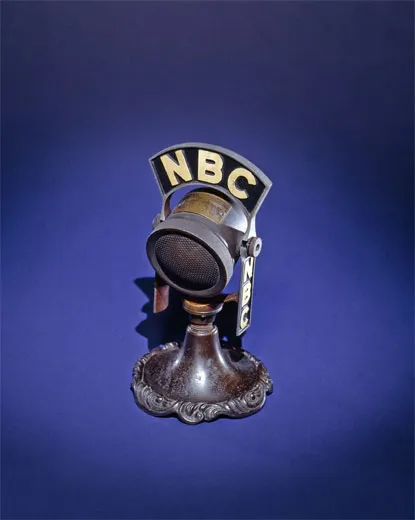

That's because Lincoln's hat, Kermit and more than 150 other iconic items from the National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center (NMAH), which closed in September for a major architectural renovation, are now on display in a unique exhibition, "Treasures of American History," at the National Air and Space Museum.

NMAH will reopen, better than ever, in the summer of 2008. "Treasures," on view until the spring of 2008, is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see some of NMAH's most valuable artifacts in a context that provides a dramatic overview of the entire breadth and extraordinary diversity of American history—its challenges, remarkable individuals and amazing accomplishments.

In a single gallery, visitors see the light bulb Thomas Edison used in his first public demonstration, the desk on which Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence, Jacqueline Kennedy's inaugural gown, Dorothy's ruby slippers, the oldest extant John Deere plow and the Woolworth's lunch counter from the 1960 Greensboro sit-in, a poignant reminder of the heroism of the civil rights movement.

"Treasures" is organized in four themes: Creativity and Innovation, American Biography, National Challenges and American Identity. (A book based on the show has just been published by Smithsonian Books.) The exhibition also includes a case dedicated to new acquisitions, because even during the closing, NMAH's collections will continue to grow.

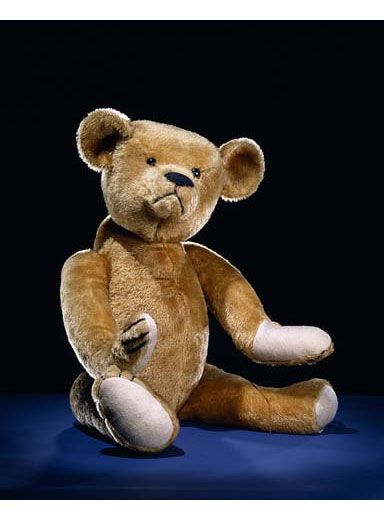

Selecting which objects would be part of the "Treasures" show was difficult, especially since an important goal for the exhibition curators was to represent the rich variety of the American story. The puffy shirt from "Seinfeld," but also General Custer's buckskin coat, is here; as is a page from the Wizard of Oz screenplay, plus Thomas Jefferson's personalized Bible. The last two are among a dozen or so NMAH items that have rarely, if ever, been on display.

Seeing many of NMAH's best treasures in the same building with the Spirit of St. Louis, SpaceShipOne and the Apollo 11 command module will no doubt inspire new realizations among visitors—new appreciations of the difficulties our nation has overcome, of our creative popular culture and of our pioneering achievements.

Ask the Curator is no longer accepting questions. Thank you for your participation.

Answers to your questions:

How do you preserve the items in the collection like Jefferson's bible?

The National Museum of American History takes its mission to care for its collections very seriously. Preserving collections is a complex undertaking involving control of the environment, proper storage materials and techniques, consideration of potential exhibit hazards, conservation treatments and careful object handling. Even when collecting objects, the curatorial staff tries to select objects that are historically important yet structurally stable. Making sure that the collection will last for the future involves nearly all departments of the museum.

Changes in the environment cause dimensional changes in objects which in turn can lead to damage - controlling humidity and temperature for storage and display is essential for long term stability of the collections. All materials used for storage must be stable for decades, if not longer, and not adversely affect the artifacts. Exhibition designers in concert with conservators analyze the materials used for exhibit cases to ensure that they do not have detrimental effects on the objects. Light can also cause damage so it must be carefully controlled.

Conservation involves examination, scientific analysis, and research to determine the original structure, materials and extent of loss of the artifacts. Conservation also encompasses the structural and chemical treatment to stabilize the object and delay any future deterioration. NMAH has four conservation laboratories dedicated to the preservation of our collections.

Steps taken to display the Jefferson bible illustrate some of our preservation work. The light levels are kept low and the page to which it is displayed is changed every three months to prevent fading of the printing or discoloration of the paper. The binding is very brittle so a special cradle supports the bible. Aside from protecting the Bible from dimensional changes, temperature and humidity are kept at a specified level in order to keep the glue in the binding from desiccating if the humidity is too low or from mold growing if the humidity is too high.

Preservation is a very complicated and involved process. Protecting and caring for the national collections is a major focus of the National Museum of American History.

How did Smithsonian get these things? Were they purchased or donated?

The Smithsonian acquires almost all of its collections as gifts. Donors understand that placing much loved and often valuable artifacts in the national collections means that they will be accessible to a broad public and cared for and preserved for perpetuity.

While most donations have come from the owners themselves, some of the National Museum of American History's most prized objects have been “inherited” from other institutions, such as the desk on which Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence. It was given by Jefferson to his favorite granddaughter, Eleanora Wayles Randolph Coolidge, and her husband, Joseph Coolidge Jr., as a wedding present in 1825. For over 50 years the desk was much revered by the family and occasionally exhibited in Boston. Upon the death of Joseph in 1879 (Ellen had died in 1876), the children presented the desk to President Rutherford Hayes as a gift to the country. For more than 40 years it was displayed at the Department of State as an icon of American democracy. In 1921 Secretary of State Charles Hughes transferred the desk to the Smithsonian, recognizing that the museum could better preserve and display this treasure.

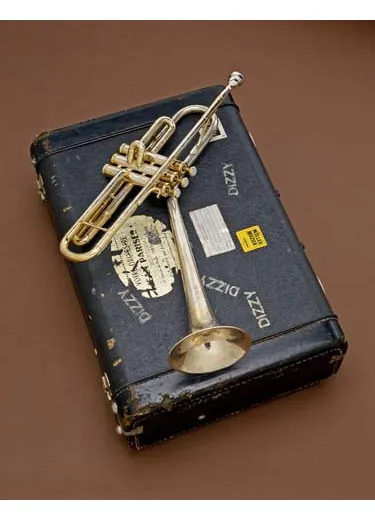

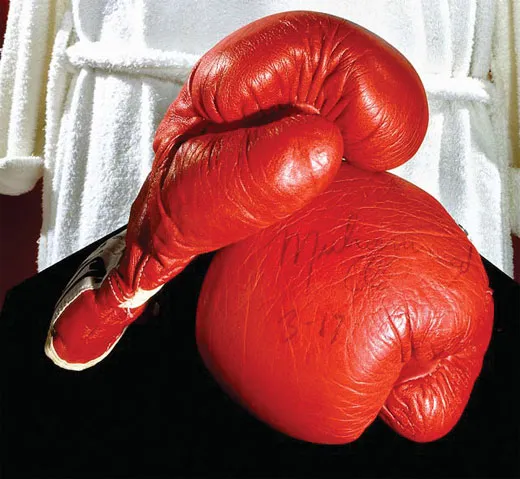

A full list of individuals and organizations who donated artifacts featured in the Treasures exhibition is provided on the Muhammad Ali donated his boxing gloves, and Alexander Graham Bell donated his telephone, for example – as well as ordinary Americans who generously chose to share their treasures with the nation.

When the museum reopens, can we still see everything in the exhibit?

When the museum reopens in 2008 many of the artifacts in the Treasures of American History exhibition will go back on display in exhibitions like Price of Freedom and The American Presidency. However some of the objects will go back into storage.

Where do you keep the items that aren't part of the exhibit?

With over 3 million objects in the collection, only a small percentage of the museum's artifacts are on view at any one moment. Some objects (especially those that researchers and staff need to see most often) are kept in collection storage rooms in the American History building. Most of the collection, however, is crated and stored offsite in warehouses in Virginia and Maryland.

How did you get the Greensboro Woolworth lunch counter from the 60's sit-in?

The acquisition of the Woolworth lunch counter is an interesting story about the process of collecting. In 1993 Bill Yeingst, a curator in what was then the Division of Domestic Life, heard an evening news report that F.W. Woolworth Corporation planned to close 900 stores nationwide. He immediately wondered whether the Elm Street store in Greensboro, North Carolina, was one of the targeted locations. The next day Bill called the Greensboro store, confirmed that is was set to be closed, and then was referred to the corporate office in New York. After talking to several people he won the company's support to acquire a portion of the lunch counter, site of perhaps the most famous civil rights sit-in of the 1960s, and preserve it in the Smithsonian collections. The company's one caveat was that the Smithsonian should first obtain the support of the local community.

The tension between local and national history is something with which Smithsonian staff members constantly wrestle. A story like the Greensboro sit-in is both local and national, and the danger is that a big institution such as the Smithsonian might swoop into town and deprive a community of their own history. Sympathetic to this concern, Bill and other members of the National Museum of American History staff traveled to Greensboro to meet with members of the City Council, leaders of the African American community, and representatives of a small museum set up to preserve the store and eventually convert it into a civil rights museum. After extensive discussions everyone was comfortable that it would be in the best interests of all if an eight foot section of the lunch counter would be removed and shipped to Washington, DC.

Since its arrival at the National Museum of American History, the lunch counter has been on almost constant display, earning the brave protestors of Greensboro, North Carolina, the respect and honor they deserve in helping end “Jim Crow” segregation.

How is the decision made to collect an item, such as Seinfield's puffy shirt, for posterity? How do you know that it will someday be historically significant?

Good question! Knowing what to collect is very difficult and there is no one right answer. Most curators prefer not to collect present day artifacts because it is difficult to separate the seeming importance of current events from what is of long lasting historical importance. The advantage of collecting current day events is that artifacts are available, objects that are ephemeral have not been destroyed, and the individuals involved can be interviewed. It is much easier to collect an event present day than twenty or fifty years after the fact. The disadvantage of collecting present day is that things that seem important today can prove to be marginal in the future.

In the case of the puffy shirt (given the number of episodes of "Seinfeld" that were filmed) it is pretty clear that the show is relatively significant in the pantheon of television programs. Of course it is hard to predict whether people will think that Seinfeld is important to the history of television comedy (or some other issue) in fifty or 100 years.

Perhaps more challenging is the question of September 11. The single most asked question posed to the curatorial team regarding the Treasures of American History is why September 11 isn't represented in the exhibition. Of course a sharp viewer will recognize that the hard hat worn by iron worker Dennis Quinn (who participate in the World Trade Center clean-up) is included in the American Identity section. However the bigger question is why not include September 11 in the National Challenges section of the show? Ignorance of the collection can be dismissed as the two exhibition curators Katy Kendrick and Peter Liebhold were very familiar with the September 11 collection. Katy Kendrick co-authored the Bearing Witness exhibition and Peter Liebhold was part of the September 11 collecting team.

The reason that this chapter of American history was omitted was the demands of space constraints and more importantly the question of what the historical significance of September 11 really means. The terrorist attacks that resulted in the destruction of the World Trade towers, a portion of the Pentagon, and four jetliners were a despicable. Yet as egregious as they were the long lasting effect is not clear. Is this an opening chapter in a world war? Would the acts of September 11 be followed by similar attacks? Was September 11 justification for the invasion of sovereign nations? None of the answers is clear. The Smithsonian is committed to a balanced and fair representation of history yet how to characterize September 11 is difficult. In 20 years the topic will probably be well researched and considered by dispassionate historians but today September 11 is still part of current events — a topic that we have all lived through and with which we are personally invested.

How do you research an item? For example, how do you know the light bulb you have is Thomas Edison's from his first public demonstration.

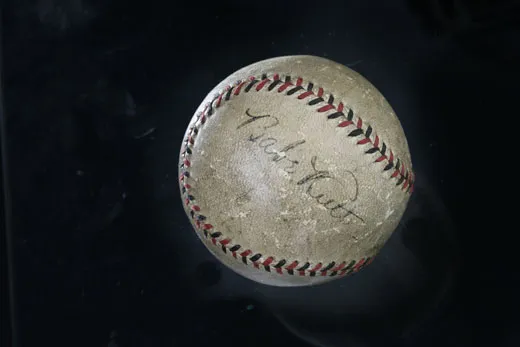

Authenticity is always a major issue when collecting artifacts. Knowing whether something is truly what it is alleged to be is a major challenge for curators. Of course physical examination can be very revealing. Is an object technically what it appears to be? With the New Year's Eve 1879 Edison demonstration bulb the object appears to be technical correct. Of course a fake is always possible. The accession records however document the provenance explaining exactly how the donor Frank A. Wardlaw, Jr. and his father Frank A. Wardlaw of New York, New York donated the bulb in 1933. The elder Wardlaw had worked for Edison and at the time of the donation and was the secretary of the Edison Pioneers.

What new acquisitions have you gotten since the exhibit started?

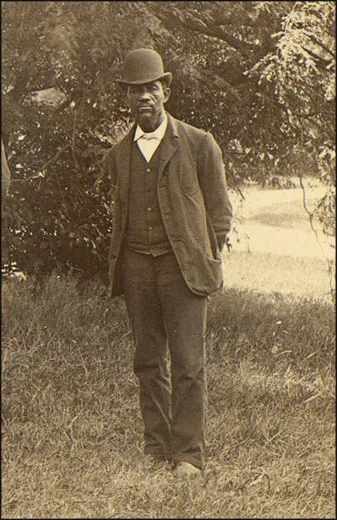

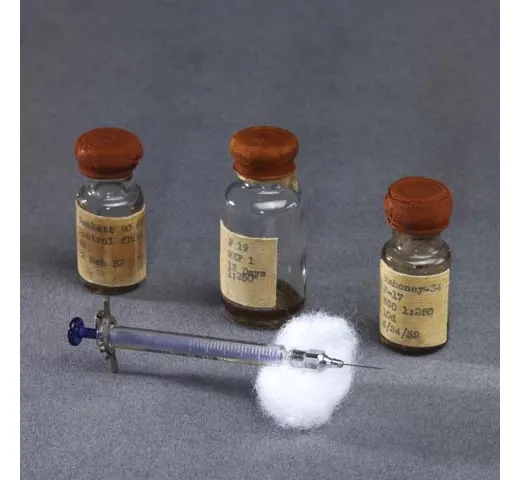

Even while closed for renovation the National Museum of American History continues to add objects to the national collections. A few of the recent acquisitions are featured in the Treasures of American History New Acquisition case. Items displayed so far include artifacts documenting Hurricane Katrina, a group of objects donated by Sylvester Stallone from the early Rocky motion pictures, a typewriter and Dictaphone from civil rights lawyer Charles Houston, medical scrubs from pediatric neurosurgeon Ben Carson, and an artificial heart from Robert Jarvick.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lawrence-small-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lawrence-small-240.jpg)