Top 10 Unforgettable Editorials

These editorial voices rose above the America clamor with words we will never forget

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/unforgettable-editorials-631.jpg)

1. “Yes, Virginia.…”

“Is there a Santa Claus?,” 8-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon asked The Sun of New York in a letter to the editor. Francis P. Church’s answer, printed on September 21, 1897, was a masterpiece of decisiveness (“Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus”) and evasion (“He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy.”) Church’s judgment that “a thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood” could also stand for his prose.

2. “Manifest destiny”

John L. O’Sullivan, editor of both a magazine titled The Democratic Review and the New York Morning News, first used the phrase in the July-August 1845 issue of the Review, to argue for annexing Texas. But, writes historian Julius W. Pratt, the phrase didn’t gain much traction because that issue was pretty much settled. While the United States and Britain were arguing over Oregon, O’Sullivan repeated himself in the Morning News of December 27, 1845: “Away, away with all these cobweb issues of rights of discovery, exploration, settlement, continuity, etc.… our claim to Oregon would still be best and strongest. And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us.” And suddenly, American expansionism had a new motto.

3. “Go West, young man.”

Horace Greeley’s corollary to manifest destiny has stood for a century and a half. Except Greeley seems never to have written or said it. Thomas Fuller, writing in the Indiana Magazine of History in September 2004, says the phrase occurs nowhere in Greeley’s New York Tribune. Fred R. Shapiro, editor of the Yale Book of Quotations, says it doesn’t appear in Greeley’s book Hints Toward Reform (1850), a commonly cited source for the quote. An 1855 Greeley biography, Shapiro writes, records his counsel to aspiring young men as: “[T]urn your face to the Great West, and there build up a home and fortune.” Thus the difference between good advice and a great phrase.

4. “What’s the matter with Kansas?”

In 1896, the Sunflower State had been losing population, wealth and prestige for years. The legendary William Allen White of the Emporia Gazette blamed the state’s leadership and electorate, which he saw as backward and self-destructive. On August 15 of that year, he published a screed of such cold reasoning and pyrotechnic fury (sample indictment: “We have raked the ash heap of human failure in the state and have found an old hoop skirt of a man who has failed as a business man, who has failed as an editor, who has failed as a preacher, and we are going to run him for congressman-at-large”) that the question he used to frame his argument became its own answer.

5. “Ford to City: Drop Dead”

Yes, it’s a headline, not an editorial, but it reflects no mean exercise of editorial license by the New York Daily News, which put it on its front page of October 30, 1975. The day before, President Gerald R. Ford did say he would veto any bill “that has as its purpose a federal bailout of New York” because responsibility for the city’s looming bankruptcy “is being left on the front doorstep of the federal government—unwanted and abandoned by its real parents,” whom he identified as city and New York State officials. He also said that if the city defaulted, his administration would help ensure that essential services weren’t interrupted, and one of his economic advisers said that help “could include money.” Eventually, the city got its finances in order, with the help of federal loans and loan guarantees. By then the headline had become immortal.

6. “The hot squat”

In 1975, Leonard Edwards of Philadelphia was awaiting trial for murder and the rape of a 14-year-old girl. But he had already been convicted of two murders, and a jury had sentenced him to death for one of them. Richard Aregood of the Philadelphia Daily News believed that “it’s about time for Leonard Edwards to take the Hot Squat,” and said so in an editorial on November 21. But Edwards never got the electric chair; the Pennsylvania Supreme Court invalidated the state’s death-penalty statute, and he died in prison in 1988. But “hot squat,” which had been a fading remnant of 1920s slang, received new life, even as lethal injection replaced the chair for state-sanctioned execution.

7. “Wrong, wrong, wrong”

Historically, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger helped lead the charge against the civil rights movement in Mississippi. But in September 1982, to mark the 20th anniversary of James Meredith’s integration of the University of Mississippi, it printed an editorial that began, “We were wrong, wrong, wrong.” That was the work of a new editor, Jackson native Charles Overby, who was working for a new owner, the Gannett chain. “But for the reader, it was the same newspaper,” says Overby, now chairman and CEO of the Freedom Forum and the Newseum in Washington, D.C., “and I thought we owed it to the community to recognize a change in consciousness that had taken place, both within the paper and out in the community.” He lays no claim to originating the phrase. But given the context, his use of it resonates.

8. “War to end all wars”

Actually, it began as “the war that will end war,” which was the headline on an H.G. Wells article in the British newspaper the Daily News and Leader on August 14, 1914, arguing for war against German militarism because such a cataclysm would lead to a permanently improved society. “We mean to conquer,” he wrote. “We are prepared for every disaster, for intolerable stresses, for bankruptcy, for hunger, for anything but defeat.” Popular usage soon honed the phrase into the “war to end all wars,” which turned out to be an all-too-hopeful reference to World War I.

9. “Times that try men’s souls”

Thomas Paine (writing under the pseudonym “the Author of Common Sense”) entered the American lexicon even before there was an American lexicon: “These are the times that try men’s souls” is the first line of the first of 16 pamphlets he published over the course of the American Revolution, from 1776 to 1783. Paine’s second line—“The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country…”—immediately expanded the lexicon.

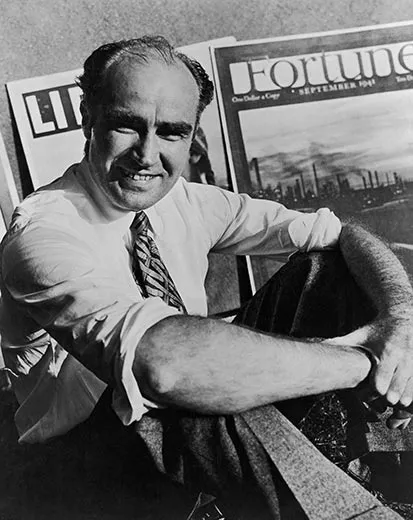

10. “The American century”

Ten months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Henry Luce sought to rouse the readers of LIFE magazine from any lingering isolationism in a 6,600-word essay bearing that headline and rising to a distillation of Luce’s credo: “Throughout the 17th Century and the 18th Century and the 19th Century, this continent teemed with manifold projects and magnificent purposes. Above them all and weaving them all together into the most exciting flag of all the world and of all history was the triumphal purpose of freedom. It is in this spirit that all of us are called, each to his own measure of capacity, and each in the widest horizon of his vision, to create the first great American Century.” In time, Americans did.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)