Top 10 Real-Life Grinches Who Did Their Best to Steal Christmas

These historical humbugs rival Ebenezer Scrooge and the Grinch in their lack of holiday spirit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/e7/45e7f219-ae6f-4108-9da8-8ad474dcbde4/the-grinch-movie-header.jpg)

With the release of yet-another adaptation of Dr. Seuss' The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, here's a look at 10 instances of people who deserved a bit of coal in their Christmas stockings.

1. Brock Chisholm was a distinguished Canadian psychiatrist who, as the first director-general of the World Health Organization, came to be called the “doctor to the human race.” But he was also known for telling an Ottawa home-and-school association in 1945: “Any child who believes in Santa Claus has had his ability to think permanently destroyed. … Can you imagine a child of 4 being led to believe that a man of grown stature is able to climb down a chimney…. That Santa Claus can cover the entire world in one night distributing presents to everyone! He will become a man who has ulcers at 40, develops a sore back when there is a tough job to do, and refuses to think realistically when war threatens.” When a reporter gave him a chance to clarify his remarks, Chisholm said that “Santa Claus was one of the worst offenders against clear thinking, and so an offense against peace.”

2. The Rev. Paul Nedergaard raised a furor in Copenhagen in 1958 when he denounced a Danish child-welfare agency’s fund-raising effort because it involved the sale of Christmas seals bearing an image of Santa Claus. “These seals bear a symbol of a pagan goblin,” he said. “You should refuse to buy them. Find some other way to aid the welfare organization.” Danes were already up in arms over some remarks on Santa made in Copenhagen just 10 days earlier by…Dr. Brock Chisholm.

3. The British officer who ended the Christmas truce of 1914 might have lived in infamy—if someone had recorded his name. The unsanctioned truce erupted after British and German troops, upon listening to each other’s caroling throughout that Christmas Eve, left their trenches at dawn to fraternize, trading cigarettes and plum pudding and even kicking around a soccer ball. But then the British officer ordered his men back to their posts; firing resumed a few hours later. And officers on both sides kept a vigil against similar outbreaks of humanity every December for the rest of the war.

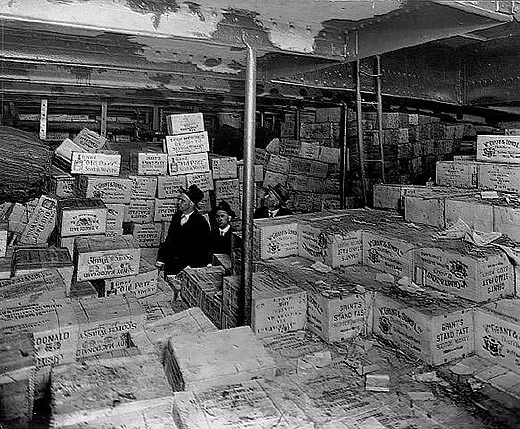

4. Diamond Jim Brady approached the recession-wracked Christmas of 1896 with a resolve to spread his wealth, and so he did, lavishing gifts on acquaintances around the country. But his generosity was fueled by ill-gotten gains. On election night that year, biographer Harry Paul Jeffers writes, Brady won about $180,000 (about $4.7 million today) by making crooked bets on the McKinley-Bryan presidential election. Then he put some of those winnings into a pump-and-dump scheme involving stock in the Reading Railroad, which was had just emerged from receivership. Brady, Jeffers writes, sold out in time to enrich himself by $1.25 million (or about $33 million today).

5. DJ Dick Whittinghill of KMPC in Los Angeles refused all requests that he play cuts from Elvis’s Christmas Album, a monumental release in November 1957 that included not only “Blue Christmas,” “White Christmas” and “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” but also “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” According to Linda Martin and Kerry Segrave’s book Anti-Rock, Whittinghill said that exposing the youth of L.A. to the Presley versions of such songs would be “like having Tempest Storm give Christmas gifts to my kids.” (Tempest Storm was then one of the biggest names in burlesque.)

6. The U.S. Coast Guard had to add rumrunners to its list of coastal threats after Prohibition began in 1919, and by December 1924 there were ominous signs that the Coasties’ vigilance was wreaking havoc in the trade. “Rumrunning has altered almost unbelievably,” New York Times reporter James C. Young wrote that year, reprising a story he had written the year before. “The holiday aspect is gone. The rules are changed. The amateur is no more. Bargain days along Rum Row have ended.” Better enforcement, Young reported, had made the business unsafe for the little guy—and left an opening for criminal syndicates.

7. Ambrose Bierce was as famous for his misanthropy as he was for his short stories. He called Christmas a “bogus holiday,” and his baleful outlook extended to his own mother, according to Bierce biographer Roy Morris Jr. As a young boy Bierce asked her if there really was a Santa Claus, and she told him there was; he soon found out otherwise. “I proceeded to detest my deceiver with all my little might and main,” he recalled as an adult. “And even now I cannot say that I experience any consuming desire to renew my acquaintance with her in that other life to which, she also assured me, we hasten hence.”

8. Oliver Cromwell, the author of England’s interregnum, did not ban Christmas, but he led the movement that did. In 1647—six years before Cromwell established the English Protectorate—the Puritan-minded Parliament, fearful that feasting, caroling and wassailing was leading to disorder (or enjoyment), outlawed Christmas celebrations. Trees? Gone. Nativity scenes? Gone. Decorations? Gone. The whole dreary ban lasted until Cromwell was overthrown in 1660.

9. The General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, another Puritan-minded institution, in 1659 ordered that “whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way…shall pay for every such offense five shillings as a fine to the county.” This ban lasted 22 years, and Christmas celebrations in Boston didn’t really recover for a century or more.

10. First James Jameson of Los Angeles stole a set of ivory-and-gold false teeth in December 1907. (“They are showy,” reported the Los Angeles Times, “the kind a man may wear on state occasions, to weddings, dinner, or to the club. They are also working teeth, fit to chew plain corn[ed] beef and cabbage as well as quail on toast.”) Then Jameson tried to sell the gold to a jeweler. And then he got arrested, meaning, as the Times noted, that the teeth, which a “toothless individual had hoped to use in chewing up his Christmas turkey,” would now be “marked with a big sign, ‘Exhibit A,’ and they will be put on some dusty shelf in the courtroom and have a rest for a while.”

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article included a photo of film actor Edward Arnold portraying Diamond Jim Brady. That photo has been replaced with one of the real-life Diamond Jim.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tom-frail-head-shot.jpeg)