To Be…Or Not: The Greatest Shakespeare Forgery

William-Henry Ireland committed a scheme so grand that he fooled even himself into believing he was William Shakespeare’s true literary heir

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shakespeare-hoax-William-Henry-Ireland-631.jpg)

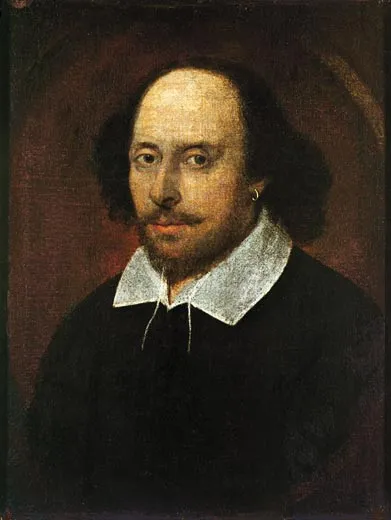

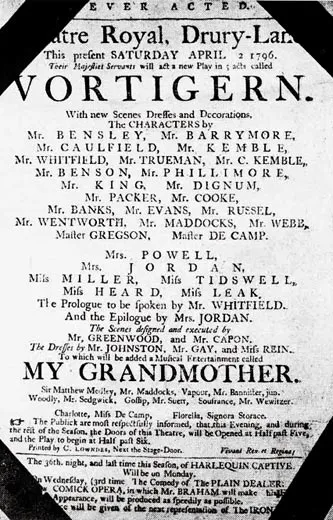

In the spring of 1795, a parade of London notables—scholars, peers, a future bishop, England’s poet laureate—called at the curio-filled home of an antiquarian named Samuel Ireland. They had come to see some papers that Ireland’s 19-year-old son, William-Henry, said he had found while rummaging in an old trunk. Scribbled in faded ink on yellowed paper, they included letters, poetry and other compositions apparently written and signed by William Shakespeare. Until now, nothing in the Bard’s own hand was known to survive, except four signatures on legal documents. Most astonishing of all was part of an unknown play purportedly by Shakespeare—a thrilling new addition to the playwright’s canon.

James Boswell, Samuel Johnson’s esteemed biographer, was one of the visitors. Seated in the Irelands’ study, Boswell, now portly and double-chinned, held the various papers up to the lamp and squinted at the florid penmanship for long minutes. Several times, William-Henry would recall, the great man interrupted his inspection to gulp hot brandy and water. Finally, he set the documents down on a table, lowered his bulk unsteadily in genuflection and kissed the topmost page. “I shall now die contented,” he breathed, “since I have lived to see the present day.” He died three months later at age 54, presumably content.

Much later, William-Henry would say he had been astonished by the brouhaha the “discovery” caused. What had started as a ploy to win the respect of his chilly, Shakespeare-worshiping father grew quickly into one of the most audacious literary hoaxes in history. In a burst of manic energy in 1795, the young law clerk produced a torrent of Shakespearean fabrications: letters, poetry, drawings and, most daring of all, a play longer than most of the Bard’s known works. The forgeries were hastily done and forensically implausible, but most of the people who inspected them were blind to their flaws. Francis Webb, secretary of the College of Heralds—an organization known for its expertise in old documents—declared that the newly discovered play was obviously the work of William Shakespeare. “It either comes from his pen,” he wrote, “or from Heaven.”

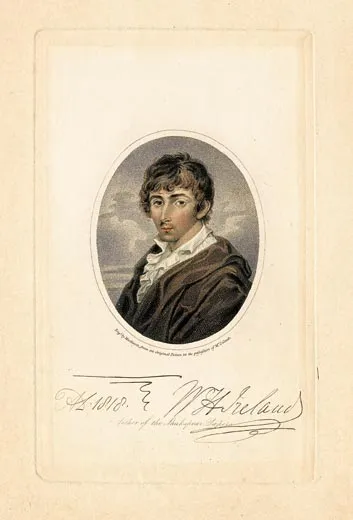

William-Henry Ireland was an unlikely Shakespeare. He dreamed of being an actor, a poet or perhaps a playwright, but he had been a dismal student, rarely applying himself to his lessons and regularly caned for misbehavior. One of his headmasters, he later recalled, told his father “that I was so stupid as to be a disgrace to his school.”

Even the boy’s parents saw him as a dullard. Samuel Ireland, a self-important and socially ambitious writer, engraver and collector, went so far as to hint that William-Henry was not his son. The boy’s mother did not acknowledge her maternity; as Samuel’s mistress, she raised William-Henry and his two sisters by posing as a live-in housekeeper named Mrs. Freeman. Samuel had found the boy an undemanding job as an apprentice to a lawyer friend whose office was a few blocks from the Irelands’ home on Norfolk Street in the Strand, at the edge of London’s theater district. At the lawyer’s chambers, William-Henry passed his days largely unsupervised, surrounded by centuries-old legal documents, which he would occasionally sift through, when asked.

He might have lived out his days in obscurity had it not been for his father’s obsession with collecting antiquities. To call on the Ireland home was to step inside Samuel’s cabinet of curiosities. Here were paintings by Hogarth and Van Dyck, rare books, a piece of a mummy’s shroud and a silver-trimmed goblet carved from the wood of a mulberry tree that Shakespeare was said to have planted in Stratford-upon-Avon.

“Frequently,” William-Henry recalled in 1832, “my father would declare, that to possess a single vestige of the poet’s hand-writing would be esteemed a gem beyond all price.”

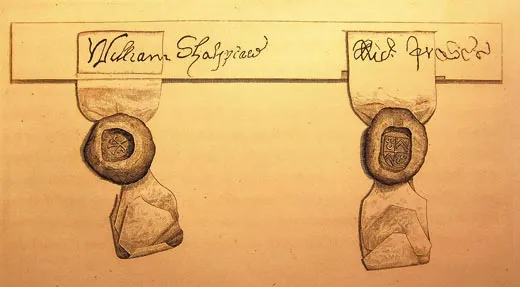

Exactly when the idea of forgery took root in William-Henry’s mind is unclear. For all his dreams of being a writer, he had produced at most a handful of poems. Shortly before Christmas in 1794, he decided to try his hand at something new. In one of his father’s books, he had noticed Shakespeare’s wobbly signature on a facsimile of an old deed. William-Henry quietly carried the book to the law chambers, where he practiced tracing the signature until he could copy it with his eyes shut. Using blank parchment he cut from an old rent roll, he used ink diluted with bookbinders’ chemicals to write a new deed. He darkened the ink by holding the parchment close to a flame, then attached wax seals he had cut from an old deed in the office.

After dinner a few evenings later, William-Henry walked into the Ireland drawing room, pulled the new deed from inside his coat and gave it to his father, saying more loudly than he intended, almost as if in defiance: “There, sir! What do you think of that?”

Samuel unfolded the deed and examined it in silence for several minutes, paying special attention to the seals. At last, he refolded the parchment. “I certainly believe it to be a genuine deed of the time,” he said, more calmly than William-Henry had hoped.

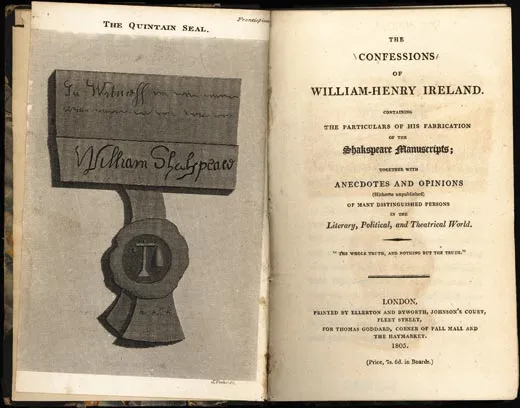

If the collector was less than convinced, his doubts soon vanished. The next morning, he showed the deed to a friend, Sir Frederick Eden, an expert on old seals. Eden not only pronounced the deed authentic, but also identified the image stamped in the seal directly below Shakespeare’s signature. The indistinct T-shaped outline in the wax (whichWilliam-Henry hadn’t even noticed) was a medieval device called a quintain, Eden explained, a swiveling horizontal bar mounted on a post at which a young horseman would aim his lance when learning to joust.

As to why the Bard had chosen it as his insignia—why, of course, it was an object at which a rider would “shake” his “spear.” The two men were exhilarated by their discovery. How could the Bard’s signature be anything but authentic, sealed as it was with his own distinctive emblem?

From this William-Henry drew an important lesson: people tend to see what they want to see. All the forger does is suggest a plausible story; his victims fill in the details.

Word spread quickly that the deed had been found, and small groups of Samuel Ireland’s friends and fellow collectors would convene in the drawing room in the evenings to discuss it.

“Several persons told me,” William-Henry wrote two years later, “that wherever it was found, there must undoubtedly be all the manuscripts of Shakspeare [sic] so long and vainly sought for.” He said he had found the deed while rummaging in an old trunk belonging to a Mr. H., a wealthy gentleman friend who wished to remain anonymous. Mr. H., he added, had no interest in old documents and told him to keep whatever he fancied.

His father badgered him relentlessly for more papers. “I was sometimes supplicated; at others, commanded to resume my search among my supposed friend’s papers,” William-Henry recalled years later, “and not unfrequently taunted as being an absolute idiot for suffering such a brilliant opportunity to escape me.”

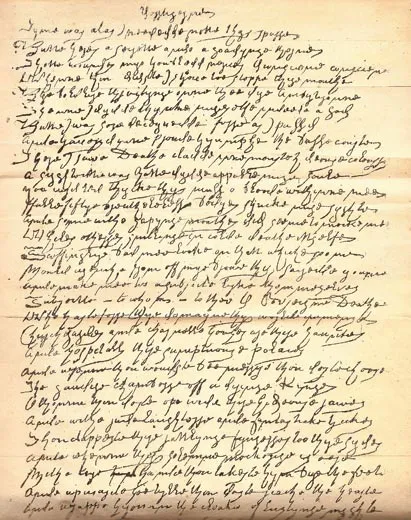

To appease his father, William-Henry promised him new treasures from the trunk. Cutting the flyleaves from old books to supply himself with antique paper, he produced an array of fakes: contracts with actors, letters to and from Shakespeare, even a love poem to the Bard’s fiancée, Anne Hathaway, complete with a lock of hair. To produce the manuscript of a well-known play, the young forger would simply transcribe the printed version into longhand. Voilà—the long-lost original! To imitate Elizabethan spelling, he sprinkled terminal e’s everywhere. He tinkered with the plays’ language as he copied them, omitting lines and adding a few short passages of his own here and there. In short order, he presented his father with an entire first draft of King Lear, followed by a fragment of Hamlet.

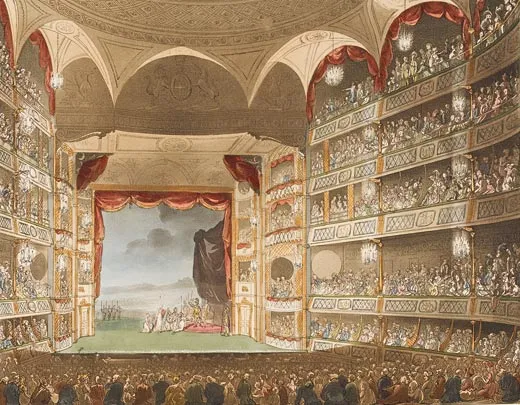

Many of those who came to Norfolk Street to judge the papers’ authenticity were unsure of what they were looking for, because drastically rewritten versions of Shakespeare’s plays were widespread. That same year, for example, the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane had staged King Lear with a happy ending: Cordelia marries Edgar, and Lear, Gloucester and Kent all survive to enjoy a peaceful dotage.

Like hoaxers before and since, William-Henry noticed that the grander his claims, the more eagerly people believed them. His most daring undertaking was that of the unknown play in Shakespeare’s handwriting that he claimed to have discovered in Mr. H.’s trunk. “With my usual impetuosity,” the forger later confessed, “[I] made known to Mr. Ireland the discovery of such a piece before a single line was really executed.” Facing his father’s growing impatience to see the play, the young man delivered a scene or two at a time, “as I found time to compose it.”

William-Henry chose as his subject a fifth-century English warlord-turned-king named Vortigern and a young woman named Rowena, with whom, according to legend, the king fell in love. Like Shakespeare before him, William-Henry drew on Holinshed’s Chronicles, a copy of which he borrowed from his father’s study. The young man wrote the play on ordinary paper in his own handwriting, explaining that it was a transcript of what Shakespeare had written. The supposed original document he produced later on, when he had time to inscribe it on antique paper in a flowery hand.

The new play was choppy and sometimes confusing, the pace uneven, the poetry often trite, but there were passages in Vortigern and Rowena that were undeniably gripping. At a banquet in Act IV, the king’s sons object when he invites comely Rowena to sit next to him in a seat that belongs to their mother, the queen. Vortigern explodes in rage:

Dare you then my power to account!

Must I, a king, sit here to be unkinged

And stoop the neck to bear my children’s yoke?

Begone, I say, lest that my present wrath

Make me forget the place by blood I hold

And break the tie twixt father and his child.

Paternal displeasure was an emotion William-Henry knew all too well. At heart, however, the play was a pastiche of characters and scenes lifted from Shakespeare’s repertoire, and it didn’t add up to much. But to those who were expecting to encounter the Bard’s newly discovered words, it read like a masterpiece.

Norfolk Street soon became a pilgrimage site for Shakespeare lovers; Samuel felt compelled to limit visiting hours to Monday, Wednesday and Friday, noon to 3 p.m. Handling of the parchment deed and the lock of hair was part of the ritual. As for the play, when visitors wondered why Shakespeare had kept this magnum opus hidden from view, William-Henry forged a letter suggesting that the playwright had viewed it as his crowning achievement and wanted more for it than his printer was willing to pay.

Transported by the thought of proximity to Shakespeare’s letters and manuscripts, Francis Webb of the College of Heralds wrote a friend: “These papers bear not only the signature of his hand, but also the stamp of his soul, and the traits of his genius.” James Boaden, a critic and editor of the London daily The Oracle, was equally certain. “The conviction produced upon our mind,” he wrote, “is such as to make all skepticism ridiculous.”

Richard Brinsley Sheridan was not so sure, but the playwright and theatrical impresario needed a hit. A free-spending, hard-drinking gambler and member of Parliament, Sheridan had just expanded the Drury Lane theater to accommodate some 3,500 customers, making it by far the largest in England. The expansion, plus losses from betting, had driven him deeply into debt. Though he’d never been a great admirer of the Bard, he was aware that staging the first première of a Shakespeare play in almost 200 years would fill his cavernous theater night after night.

In the spring of 1795, Sheridan came by the Irelands’ home to evaluate Vortigern. Seated in the study, he read a few pages, then stopped at a passage that struck him as unpoetic—clumsy, in fact.

“This is rather strange,” he said, “for though you are acquainted with my opinion as to Shakespeare, yet, be it as it may, he certainly always wrote poetry.” After a few more pages, Sheridan stopped again and looked up at his host. “There are certainly some bold ideas, but they are crude and undigested. It is very odd: one would be led to think that Shakespeare must have been very young when he wrote the play.”

But then he added that no one could doubt that the collected documents were Shakespeare’s, because “who can possibly look at the papers and not believe them ancient?” Sheridan didn’t think Vortigern was very good, but he nevertheless wanted it for Drury Lane. The play would have its première there the following April.

William-Henry was aware that the steadier the flow of visitors to Norfolk Street, the more likely that doubters would begin to make their voices heard. He was particularly nervous about a visit from Joseph Ritson, a critic known for his biliousness. “The sharp physiognomy, the piercing eye and the silent scrutiny of Mr. Ritson filled me with a dread I had never before experienced,” William-Henry would later write.

After studying the papers, Ritson wrote to a friend that they were “a parcel of forgeries, studiously and ably calculated to deceive the public.” He judged them to be the work of “some person of genius and talents”—not one of the Irelands, certainly—who “ought to have been better employed.” But he kept this verdict private; after all, a scholar or antiquary risked lifelong infamy if he denounced as fraudulent a poem or a play that was later proved to be Shakespeare’s. So doubts about the papers’ authenticity took the form of rumors.

To counter them, a core group of believers, including Boswell, drew up a Certificate of Belief stating that they “entertained no doubt whatsoever as to the validity of the Shaksperian [sic] production.” Meanwhile, Samuel kept nagging his son for an introduction to Mr. H. and a chance to dig through the man’s trunk himself. William-Henry reminded his father of Mr. H.’s insistence on complete anonymity, citing the man’s dread that Shakespeare cultists would badger him with “impertinent” questions about the artifacts. After William-Henry suggested an exchange of letters instead, Samuel developed a lively correspondence with the elusive gentleman. In courteous language and graceful handwriting that the collector failed to recognize as his son’s, Mr. H.’s letters extolled William-Henry’s character and abilities.

Samuel announced plans to publish a volume containing the Shakespeare papers in facsimile. The price would be four guineas—about what a workingman earned in two months. William-Henry objected vehemently, claiming that Mr. H. had refused permission. Until now, the papers had been hard-to-read curios, available only to guests of the Irelands. Once William-Henry’s prose and poetry were set in type, the texts would be subject to clear-eyed scrutiny by strangers. “I had an idea of hazarding every opprobrium, and confessing the fact [of forgery], rather than witness the publication of the papers,” he would later write.

And yet he was also beginning to delude himself: the stunning success of his novice compositions was making him feel that he—a poorly educated lad with a pointless job, a dunce and a failure in the eyes of the world—was the Sweet Swan of Avon’s true literary heir. Of course, for the world to recognize his rare talent, he would have to reveal his authorship—and to confess to being a make-believe Shakespeare would expose the Bard’s admirers, and especially his father, to ridicule.

His father published the Shakespeare papers on Christmas Eve 1795. Several of London’s high-spirited newspapers pounced with glee. The Telegraph published a mock letter from the Bard to his friend and rival Ben Jonson: “Deeree Sirree, Wille youe doee meee theee favvourree too dinnee wythee meee onn Friddaye nextte, attt twoo off theee clockee, too eattee sommee muttonne choppes andd somme poottaattoooeesse.” Such mockery only fanned public interest. On the central question of whether Shakespeare had written the papers, most people had yet to make up their minds. Forgeries, then as now, were notoriously hard to detect from the style and quality of the writing; over the centuries, Shakespeare’s canon would be added to (Pericles) and subtracted from (The London Prodigal) as scholars debated whether the playwright was working with a collaborator and, if so, who might have written what. Samuel Ireland’s claims were no more dubious than much of what then passed for literary scholarship. And his numerous supporters included scholars, collectors, clergymen, poet laureate Henry James Pye, a gaggle of MPs and an assortment of earls and dukes.

To the few voices that had been raised publicly against them, Edmond Malone now added his. The editor of Shakespeare’s complete works, who was widely considered England’s foremost expert on the author, published a book-length exposé on the Ireland papers, attacking them as a “clumsy and daring fraud” riddled with errors and contradictions. Of a thank-you letter to the Bard supposedly written by Queen Elizabeth herself, Malone wrote that the spelling “is not only not the orthography of Elizabeth, or of her time, but is for the most part the orthography of no age whatsoever.” He noted the absurd unlikelihood that so many disparate items would end up in the same magical trunk. He didn’t know who had forged them, but he had no doubt that someone had.

More harmful than Malone’s opinion was his timing: in the hope of inflicting the most damage, he published on March 31, 1796—just two days before the première of Vortigern.

Malone’s exposé sold out before the play opened, and it caused an uproar—but it wasn’t the fatal blow he had hoped for. His arguments were too pedantic and unfocused to win over everyone, and his boastful, insulting tone didn’t help. William-Henry was grimly amused that this “generalissimo of the non-believers,” as he called the critic, took 424 pages to say the papers were such an obvious forgery that one could see through them at a glance.

In any case, few British theatergoers relied on textual analysis. John Philip Kemble, the reigning star of the London stage, doubted the play’s authenticity even as he rehearsed for the lead role, but Sheridan suggested he let the audience decide for itself: “You know very well that an Englishman considers himself as good a judge of Shakespeare as of his pint of porter.”

Vortigern’s opening-night audience would be ready to judge the play’s authorship—and by extension, that of the other Ireland papers—well before the final lines were spoken.

A full house—a first for Drury Lane’s vast new building—was on hand for the opening, Saturday, April 2, 1796. At least as many people were turned away. With all the dignity he could muster, Samuel Ireland forced his way to a large box in the center of the theater, visible to everyone. William-Henry slipped inside through a stage door and watched from the wings.

The first two acts of the five-act play went well enough. There was little of the London theatergoers’ customary heckling and catcalling, and several of William-Henry’s speeches were applauded. The echoes of familiar Shakespeare plays were impossible to miss—it was Macbeth crossed with Hamlet, with touches of Julius Caesar and Richard III. The very familiarity of the characters and situations, in fact, may have reassured many in the audience.

But not everyone. Vortigern was obviously not a theatrical masterpiece, regardless of who had written it. The first hint of disaster came in the third act, when a bit player—a skeptic, like Kemble—overplayed his lines for laughs. The crowd grew more restive in the final act, when Kemble as King Vortigern addressed Death with mock solemnity:

O! then thou dost ope wide thy hideous jaws,

And with rude laughter, and fantastic tricks,

Thou clapp’st thy rattling fingers to thy sides;

And when this solemn mockery is ended—

The last line he intoned in a ghoulish, drawn-out voice, which provoked several minutes of laughter and whistling. Kemble repeated the line—leaving no doubt as to what mockery he was referring to—and the crowd erupted again. The performance might have ended there, but Kemble stepped forward to ask the audience to permit the show to go on.

The final curtain brought enthusiastic applause as well as prolonged booing; not all of those on hand had joined in the disruptions, and many undoubtedly believed they had just witnessed a new work by William Shakespeare. But then an onstage announcement that Vortigern would be repeated the following Monday evening was shouted down. In the pit, fighting broke out among believers and nonbelievers. The chaos lasted for nearly 20 minutes, and subsided only after Kemble took the stage to announce that Sheridan’s own School for Scandal would replace Vortigern on Monday’s bill.

The reviews that began appearing in the newspapers that Monday were scorching. Taking their cue from Malone, commentators denounced Vortigern as fabricated nonsense. A few responses were more temperate. Poet laureate Pye observed that the audience’s unruliness was no proof of forgery. “How many persons were there in the theatre that night,” he asked, “who, without being led, could distinguish between the merits of King Lear and Tom Thumb? Not twenty.”

To his own surprise, William-Henry was relieved by the fiasco. His long-running subterfuge had reduced him to a state of bitter exhaustion. After the audience’s judgment, he later wrote, “I retired to bed, more easy in my mind than I had been for a great length of time, as the load was removed which had oppressed me.” But the debate over the Shakespeare papers’ authenticity persisted for months—until William-Henry confessed, to the astonishment of many, that he had written them himself.

Unable to face his father, he told his sisters, his mother and ultimately an antiquarian friend of his father’s. When they told Samuel, he refused to believe that his simple-minded son was capable of such a literary achievement.

William-Henry, infuriated, moved out of his father’s house and, in a letter, dared him to offer a reward “to anyone that will come forward & swear he furnish’d me even with a single thought throughout the papers.” If the papers’ author deserved credit for showing any spark of genius, he continued, “I Sir YOUR SON am that person.”

Samuel Ireland went to his grave four years later maintaining that the Shakespeare papers were genuine. William-Henry struggled to support himself by selling handwritten copies of them. He was considered a minor when he committed his literary deception, and he had not profited in any significant way from his escapade, so he was never hauled into court. Naively, he’d expected praise for his brilliance once he revealed his authorship. Instead, he was pilloried. One writer called for him to be hanged. William-Henry attributed his critics’ venom to embarrassment. “I was a boy,” he wrote in 1805, “consequently, they were deceived by a boy.” What could be more humiliating? Eventually, he wrote several books of poetry and a string of gothic novels, some published, some not. His notoriety as “Shakespeare” Ireland helped win his books attention.

William-Henry never expressed contrition for his escapade. Rather, he was proud of it. How many English boys had known the exhilaration of being likened to a god? For all the social snubs, the money troubles and the literary rejections he endured before dying, in 1835, at age 59, he would always console himself with the thought that once, for a glorious year and a half, he had been William Shakespeare.

Excerpted from The Boy Who Would Be Shakespeare, by Doug Stewart. Copyright © 2010. With the permission of the publisher, Da Capo Press.