These Never-Before-Seen Photos From “The New York Times” Offer a New Glimpse Into African-American History

The editors of the new book, “Unseen” talk about recognizing the paper of record’s biases

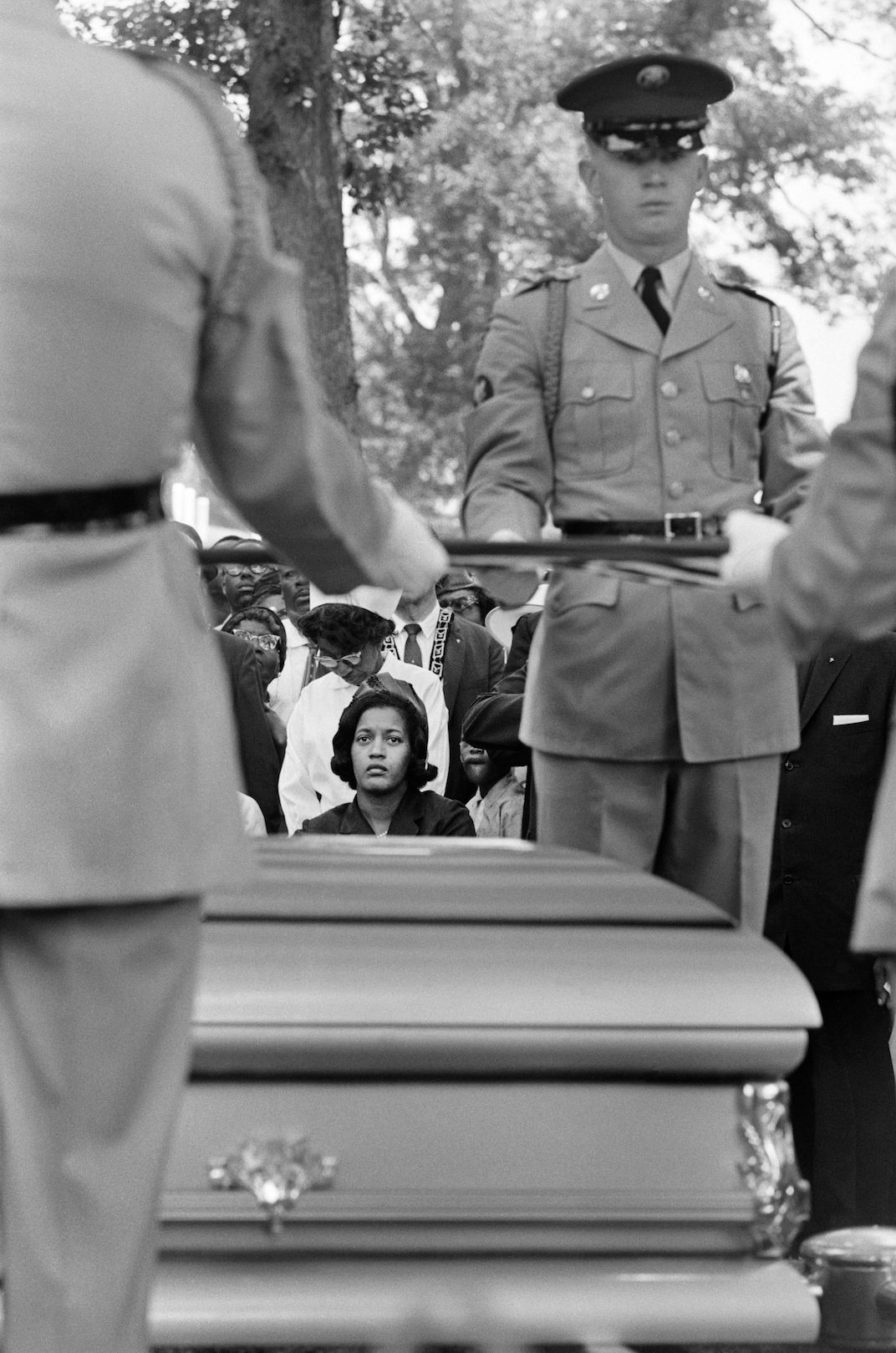

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/8c/028c0061-3319-41d6-a029-88d0eb8cf676/29_grady_ocummings.jpg)

There are about 10 million prints in the picture library of The New York Times, with anywhere from 60 million to 400 million photo negatives. Nicknamed “the morgue,” the archive is a living history of the United States. Each day, Times photographers went on assignment, capturing momentous events, leaders of politics and culture, or simply everyday life, and each night, editors selected certain photos for inclusion in the print edition.

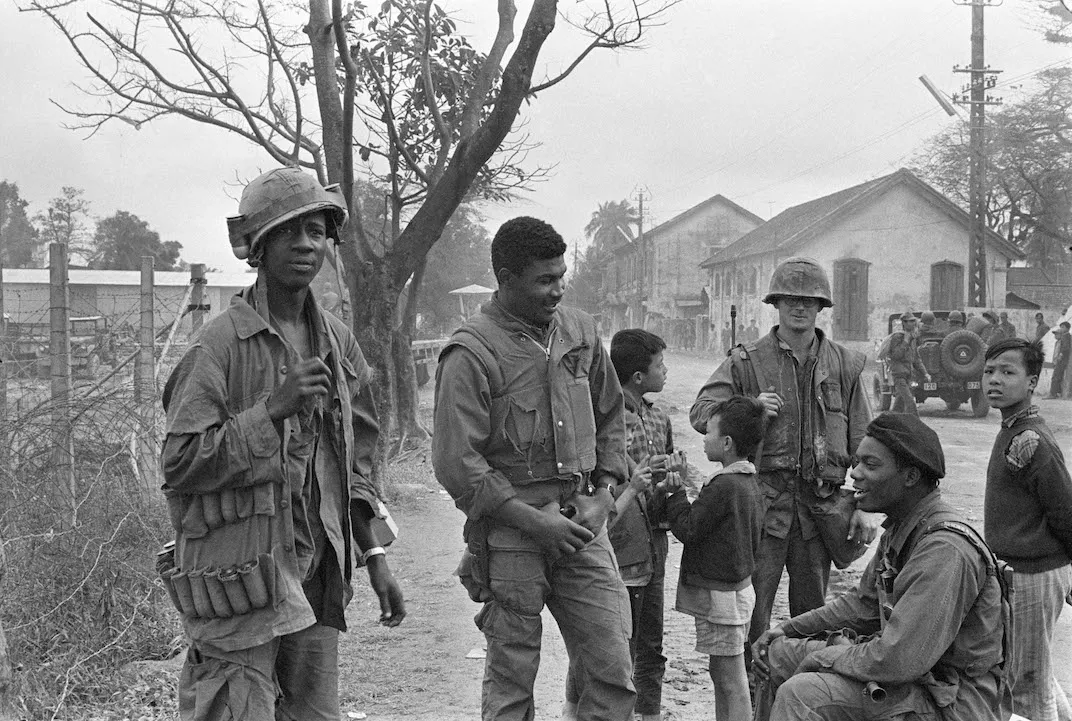

That selection process was subject to the realities of deadlines, the physical limits of the paper, but also the biases—explicit and implicit—of journalists at the time. Stunning photographs were never seen outside the newsroom, and the Times’ photographs of the African-American experience, from the likes of Medgar Evers, to parades in Harlem, to soldiers in the first Gulf War, exhibit this challenge.

Unseen: Unpublished Black History from the New York Times Photo Archives

Hundreds of stunning images from black history have long been buried in The New York Times archives. None of them were published by The Times--until now.

Since the advent of photographic technology, few groups have had a more fraught relationship with the camera than African-Americans. Pseudoscientists like Louis Agassiz used photos to objectify enslaved African-Americans, while during the same period, free black persons turned to the medium to prove their worth and expose their exploitation and oppression. Sojourner Truth became the first black woman to distribute photos of herself, selling them to fund her abolitionist work and posing for portraits on at least 14 occasions. Frederick Douglass was also a fan of the medium, but saw how easily it could be manipulated by the people behind the camera.

“This picture-making faculty is flung out into the world like all others—subject to a wild scramble between contending interests and forces,” Douglass told audiences in a lecture in 1861. “It has a mighty power, and the side to which it goes has achieved a wondrous conquest.”

And now the Times hopes to capture that power in its own book of archival photography, Unseen: Unpublished Black History from the New York Times Photo Archives. It follows a sustained enthusiasm for historical images of African-American communities, including books, documentaries and an exhibit of photographs from the New York Police Department’s surveillance team of the 1960s and ’70s.

Unseen features hundreds of photos from different facets of African-American life. Along with the photos come essays detailing the significance of the image and, sometimes, why it wasn’t published in the paper.

“We wanted to look at ourselves, too, how we covered communities of color and how we didn’t, how we contributed in some ways to the erasure of important moments and individuals,” says Rachel Swarns, one of the book’s editors and a reporter for the New York Times.

But assembling the massive collection—and verifying that the photos had never before appeared in print by cross-referencing dates and print editions of the paper—was a herculean task, says Darcy Eveleigh, the Times’ photo editor and another editor of Unseen.

“When I embarked upon [the project], my first run through was to find big names—what we have on Rosa Parks, on King, on Thurgood Marshall,” Eveleigh says. “The second round was when I just randomly pulled stacks that sounded like they may have something to do with African-American life. It was about 16 months’ worth of searching.”

Once Eveleigh retrieved the images, she shared them with a group of editors who debated what should be included. She was also sent back to the archives on a number of occasions in attempts to track down photos of important figures, some of whom were surprisingly absent from the archives, including historian and Civil Rights activist W. E. B. DuBois.

“When you’re in the nitty gritty of it, [the absence] really surprises you,” Swarns says. “But in a way, it’s not surprising. Newspapers were made by the society, they were part of the establishment at a time when the establishment was marginalizing African-Americans.”

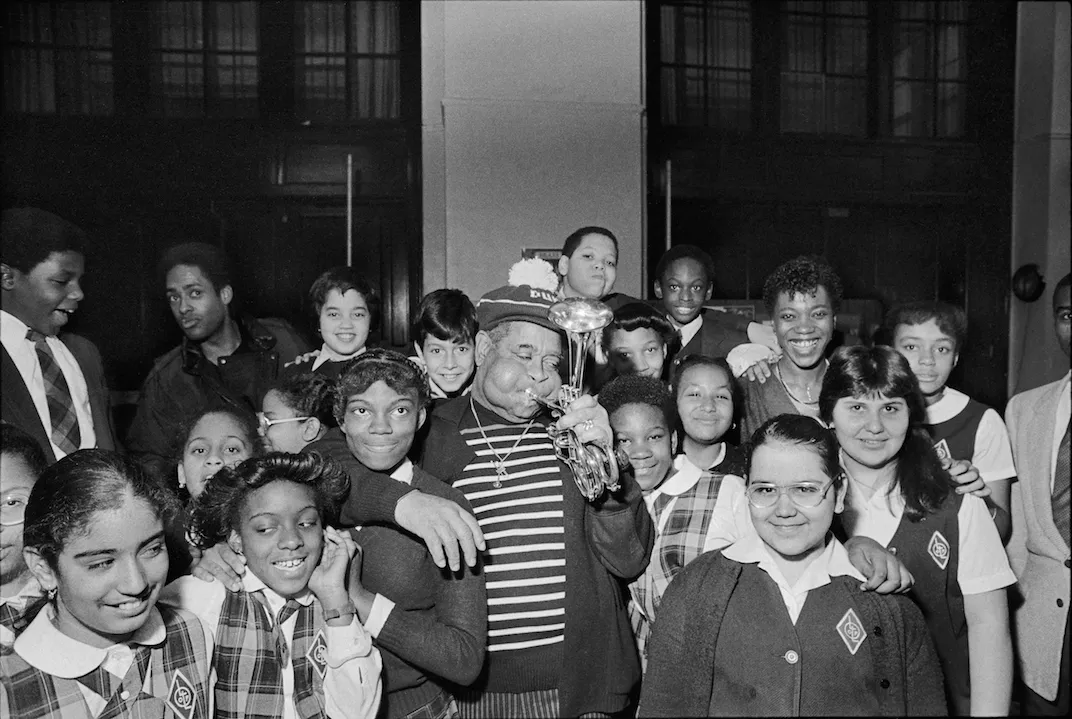

Other times, Eveleigh was able to track down certain important figures, but the editors were left puzzling over why the photos hadn’t been published in the first place. That was the case with a photo of jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. In the image, he poses with his trumpet surrounded by a group of school kids. An article ran on this appearance in the paper, but they used a simple solo shot of Gillespie instead of the group shot, possibly because of space issues. Eveleigh says the attitude at that era was, “You’re here to read the New York Times, not look at it.”

Despite the incredible amount of time spent finding the photos, Eveleigh and Swarns agree that it was a rewarding project. For Eveleigh, the most enjoyable photo was one of Civil Rights leader Grady O’Cummings. When Swarns found the photo of him from 1963 and began looking into his back story, she was surprised to see an obituary for him in 1969 and a death certificate from 1996. “We found out that he faked his death in the New York Times, and the paper never corrected the record on it,” Eveleigh says, adding that it’s only the second time the obituary editor could recall having seen a fake obituary. “That’s my favorite story.” (O’Cummings reasons for faking his death were particularly poignant—he said his family received death threats from members of the Black Panthers.)

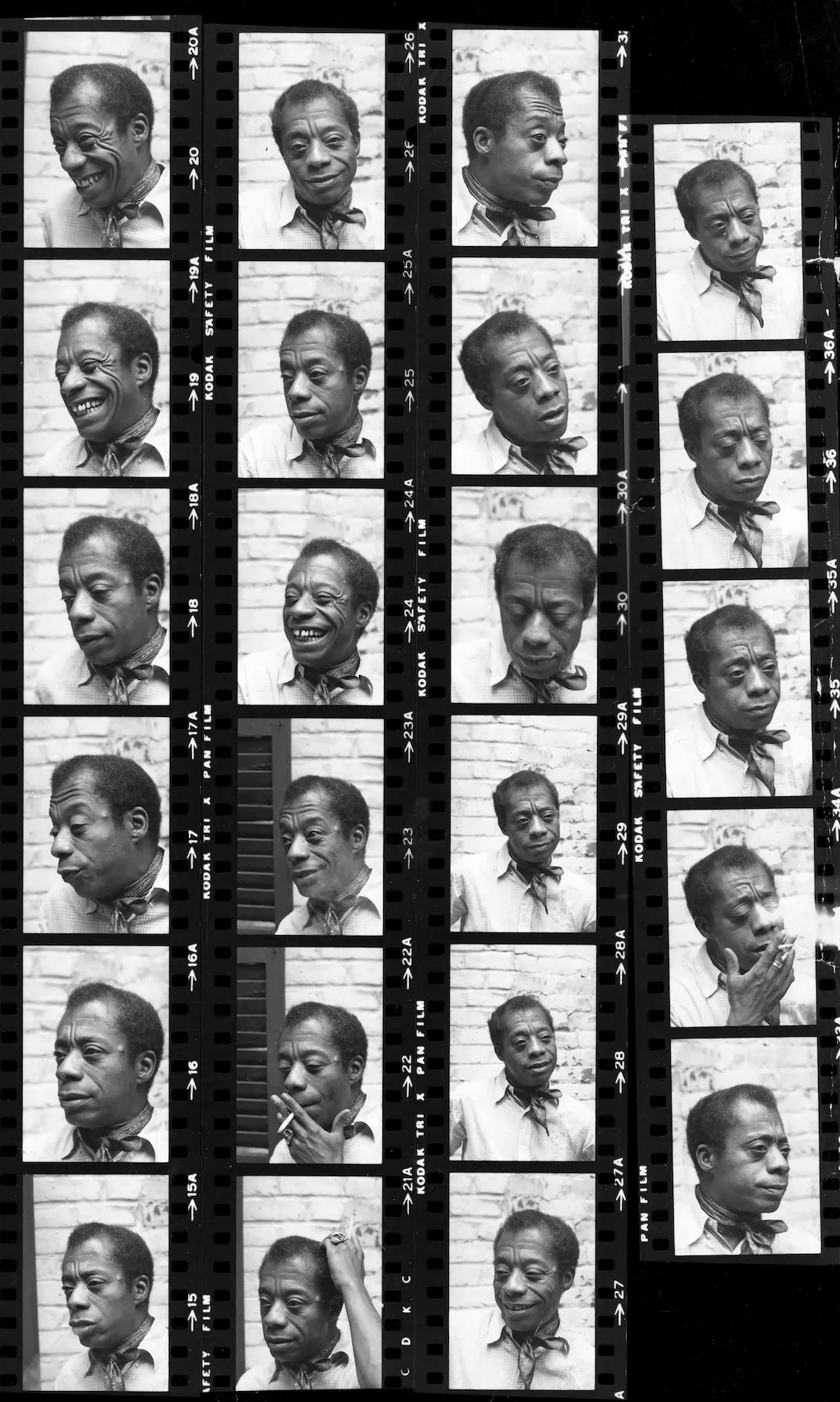

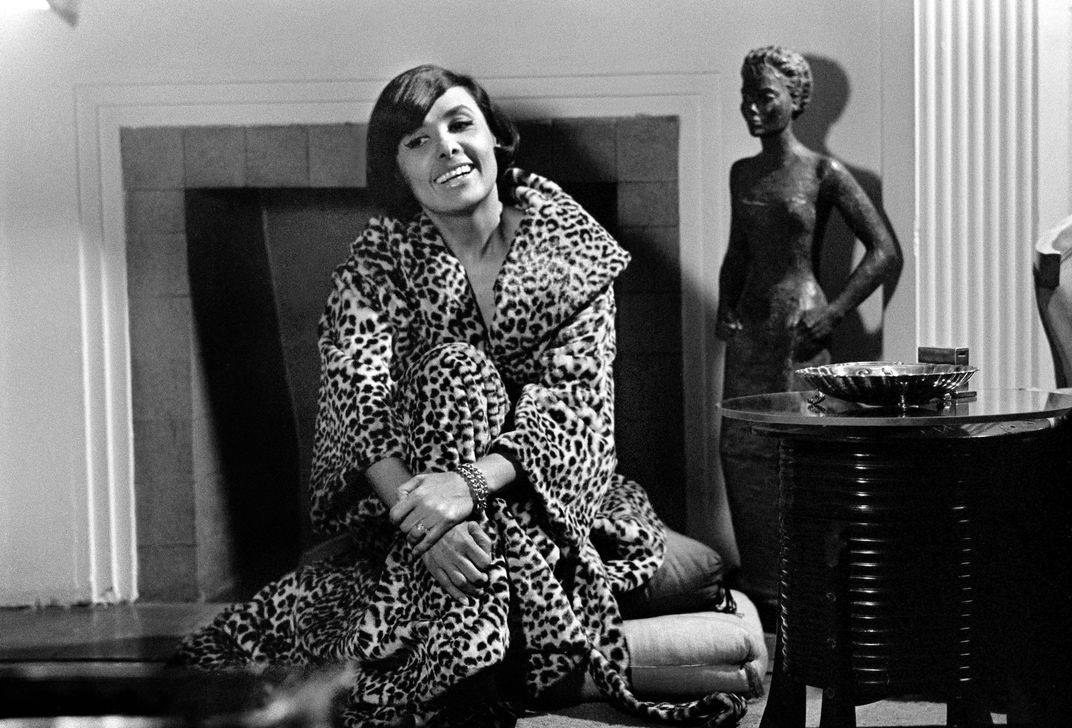

For Swarns, the number of photos she loves are almost too numerous to count. From an image of singer and actress Lena Horne in her Manhattan apartment, to a photo of psychologist Kenneth B. Clark relaxing in his back yard, she’s struck by the intimate moments of famous African-Americans caught on camera. She especially likes the series of James Baldwin. “It’s almost like a little motion picture of him as he’s doing the interview. Laughing, then very sober, then smoking a cigarette, eyes closed, eyes open—it’s just remarkable,” Swarns says.

Both editors hope that readers will share the same thrill of discovery when they page through the book. There are no organizing chapters, no chronological division. Instead what emerges is a broader portrait of the highs and lows of African-American life. It’s a model they hope other papers will consider imitating, revealing facets of the American experience that have previously been ignored and forgotten.

“There’s so much newspapers can do on all kinds of subjects,” Swarns says, adding that photo archives are “an endless and rich source for media companies.”

Darcy Eveleigh and Rachel Swarns will be speaking at a Smithsonian Associates event Monday, December 11 at the Smithsonian's S. Dillon Ripley Center in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)