The Unsolved Case of the “Lost Cyclist”

Author David V. Herlihy discusses his book about Frank Lenz’s tragic failed attempt to travel the world by bicycle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Thomas-Allen-and-William-Sachtleben-in-China-631.jpg)

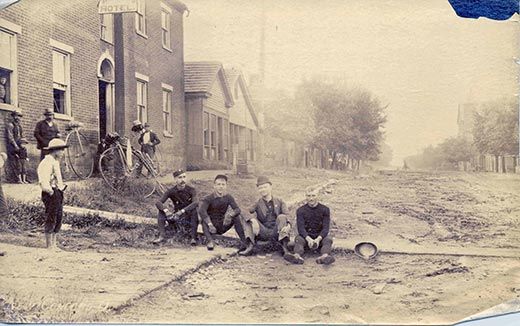

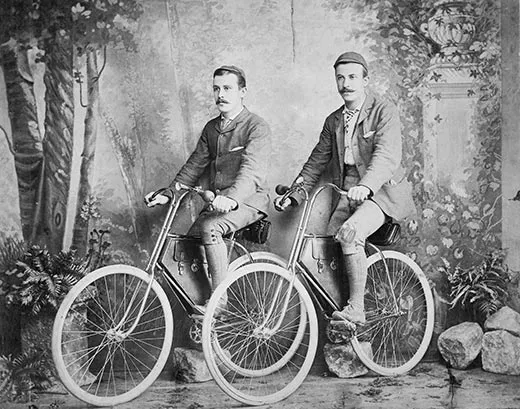

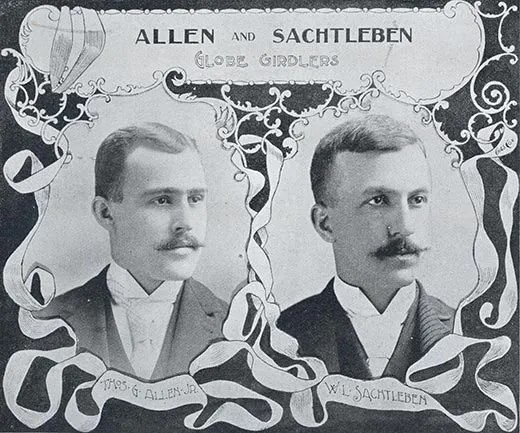

The sport of high wheel riding was introduced to the United States from England in the late 1870s. In its first decade, it was an elitist, fringe sport. American cyclists were predominately well-to-do young men daring enough to mount high wheelers—bikes with a large front wheel and tiny rear wheel. In 1892, Frank Lenz, an accountant turned long-distance cyclist from Pittsburgh, set off on a solo around-the-world tour to promote the “safety bicycle,” a successor to the high wheeler and precursor to today’s road bike that would ultimately spark the great, turn-of-the-century bicycle boom and transform cycling into a popular sport. In his new book, The Lost Cyclist, bike historian David V. Herlihy tells the story of Lenz, his mysterious disappearance in a volatile part of east Turkey and the ensuing investigation led by William Sachtleben, a fellow cyclist who succeeded in circumnavigating the world by bike.

What drew you to this story?

It’s been about 20 years since I first delved into bicycle history. I was familiar with the [bicycle] boom-era literature of the 1890s. Lenz is a name that comes up a fair amount. In the summer of 1890, he rode to St. Louis along the National Road from Pittsburgh. Then, in August 1891, he rode from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. But of course when he embarked on this around-the-world journey, he became quite the celebrity. When he disappeared in Turkey a few years later, he became even more famous. I knew there was a mystery surrounding him and found him an intriguing character. But I also knew, as well known as he was in the 1890s, he was completely forgotten afterwards.

Lenz’s accounts of his pedal across North America and Asia, published by his sponsor Outing magazine, had, as you say in the book, “an intimacy only a cyclist could enjoy.” So what intimacies did bike touring allow that other travel up until that point hadn’t?

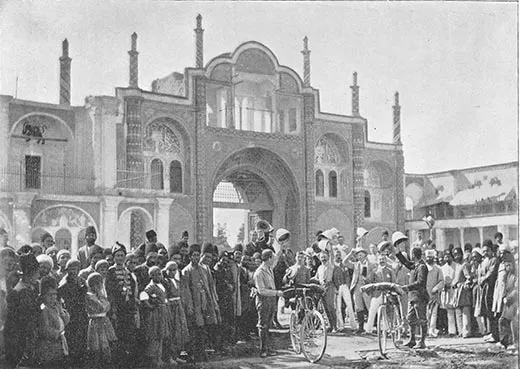

Sachtleben talked about how there is such a thing as too much comfort in traveling. In his time, only the wealthy took European tours. Typically, they traveled by luxury steamer and coach, with servants and trunks in tow. You don’t have any of that when you’re traveling by bike. You are not insulated. You’re there. You’re vulnerable. The bicycle really brings you to the people. You can’t help but interact with them. Lenz, too, recognized that travel by bicycle was a very intimate way to experience a culture. Both men became magnets for unwanted attention, not just because they were Westerners in foreign lands, but also because their vehicles were new and wondrous to the locals, who often demanded riding demonstrations.

How did you go about digging up his story?

About ten years ago, I curated a bicycle history exhibit that toured several museums. I had included a photo of Lenz in China on his bicycle. When the exhibit was up at the Springfield Science Museum in Massachusetts, I got a call or an e-mail from a young man named John Herron. He wanted me to know that he had a scrapbook full of photos taken by Lenz. It was something like 80 pages long, with very faded photos mostly of the world tour.

I also understood that the National Archives had files relating to the search for Lenz conducted by the State Department. Confident that I could find enough material for a book, I was ready to plunge right into the Lenz research. But I took the advice of an acquisitions editor at Yale University Press and wound up putting the Lenz project on the back burner to write my book Bicycle: The History.

Sometime around 2005, I was finally ready to focus on Lenz. I soon came across another collection of photos owned by John Lenz, who descends from one of Frank’s step-uncles. These photos were largely complementary to the ones in the scrapbook because they were mostly from Lenz’s pre-world trip days, when he rode the high wheeler.

As my research progressed, I realized that there was yet another interesting untold story about William Sachtleben, the cyclist who went looking for Lenz. I found lots of good material on him, too, and I concluded that I should really tell both these stories simultaneously.

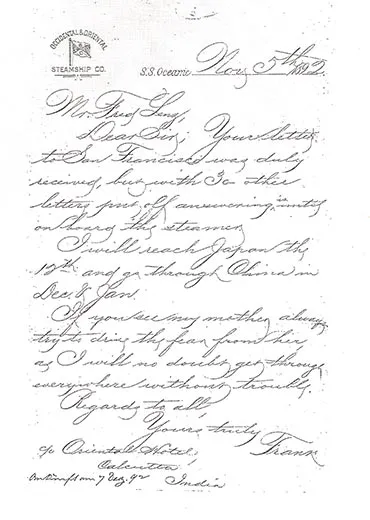

I felt reasonably satisfied after four years of intense research that I’d gotten the story about as complete as it could be without some major new discovery. There are always a few loose ends, and I’m fully expecting and hoping that new stuff comes out. I’m convinced that somewhere out there are letters Lenz sent home. John Lenz has two letters written by Lenz himself during the world tour, but I know there were many more. Hopefully the book creates more of a collective memory of Frank. Maybe it will jar somebody’s memory, and they’ll remember they have a trunk upstairs.

So, Lenz—well-intentioned pioneer or reckless adventurer with a death wish?

That’s hard to say exactly. I think he started out with some cockiness. But I do have the sense that he matured during this trip and became a little more prudent along the way. So I don’t think he had a death wish.

A near-death experience he had in China seems to have had a very sobering effect on him. In an interview he gave shortly afterwards, Lenz was asked to explain the purpose of his trip. Though the original stated objective was to promote the new safety bicycle, and there were obvious advertising interests behind it, Lenz truly seems to have sensed a higher mission. He talked about how it would prove “that there is a fraternal feeling among the human race,” and that “with civilization comes tolerance, and a more sympathetic appreciation of fellow men among all nations.”

As he was approaching Turkey, he basically had two options. He could go to Europe the direct way, across Turkey. Or he could heed the advice of missionaries and get to Europe through Russia, which was certainly more roundabout but considerably safer. I don’t think he was being deliberately reckless when he decided to go through Turkey, but he may have been a little bit overconfident at that point having survived China. For Sachtleben, Lenz’s fatal mistake was to travel alone.

What do you think really happened?

What we can rule out, in my opinion, is any notion that he went undercover and lived out his years in Turkey or Persia. I have no doubt that he died in 1894. And it’s almost certain that he did die in Turkey. Now, specifically where and how did he die? If he was killed, who killed him? Those are the questions that are still unanswered.

Lenz may have died an accidental death. We know that he had to ford a number of rivers after he entered Turkey and was heading to Erzurum, and we know that at this time of year the currents were at their strongest. It also appears that he might have been in a weakened state because he had gone through several long bouts [of sickness].

But my gut feeling is that Lenz was killed. There’s a good chance that if he was killed, he was killed by the Kurds. They did have a reputation for being a tough lot that would attack foreigners along the caravan road. Was it the Kurd [Moostoe Niseh] that Sachtleben figured? There certainly was some evidence that Lenz was attacked just outside the town where Moostoe lived, where bits and pieces of Lenz’s camera and gear were found. But one of the problems I had with that evidence is, well OK, maybe that’s evidence of an assault, but does that really show that he was murdered there? Without the body, without knowing the location of the grave, without finding the bicycle, it seems to me that you can’t completely rule out the possibility that Lenz may have been attacked there, but that he was allowed to proceed. In fact, the early reports had Lenz further up the road about 30 miles into the foothills of Erzurum, where he was allegedly killed by a different set of Kurds. Moostoe was a dastardly character who was certainly capable of killing Lenz. But then again, you can argue that maybe that was the reason that the Armenians were so keen on pinning a murder on him—to get him out of town. Bottom line is I just don’t know that Sachtleben really got to the truth. I don’t think that we can say who exactly killed Lenz or why. Maybe he was just attacked because they thought he had valuables. I certainly would have loved to solve the case, but it’s still a mystery.

Why do you think Lenz has been forgotten?

There was a lot of sympathy for Lenz and his family and friends when he was first reported missing. But over time I think the consensus arose that Lenz had been foolhardy and reckless; that he had effectively brought about his own death. In addition, the public soured very quickly on globe-girdling by bicycle. By the early 20th century, you started to see people circling the globe by motorbikes and then cars. Bicycles began to look like a very quaint and outdated mode of transportation. At the peak of the 1890s boom, prominent citizens like John Rockefeller had been riding bikes. But a decade later it was strictly a poor man’s vehicle. It was not really until the ’50s and ’60s when Americans began to see the bicycle once again as a serious adult vehicle, and by that time Lenz was long forgotten.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

I do think there’s something admirable, youthful—some would say “American”—about the spirit of Lenz’s and Sachtleben’s adventures. Their stories resonate with our notions of plucky Americans and their can-do attitudes. Despite the personal tragedies here, there is something uplifting about their willingness to see the world and their fundamental optimism. They really did have to have basic faith in humanity to think that they would return home alive. I’m hoping that readers take away a fair impression of these two young men. I didn’t try to conceal their rough edges, their recklessness, their lack of cultural sensitivity, or exaggerate what they actually accomplished. Still, on a physical level, their bicycle journeys were indisputably amazing feats. And these two truly were pioneers, in that they helped to introduce the bicycle as we know it to the general public. Their stories should be told.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)