The Traumatic Birth of the Modern (and Vicious) Political Campaign

When Upton Sinclair ran for governor of California in 1934, new media were marshaled to beat him

![]()

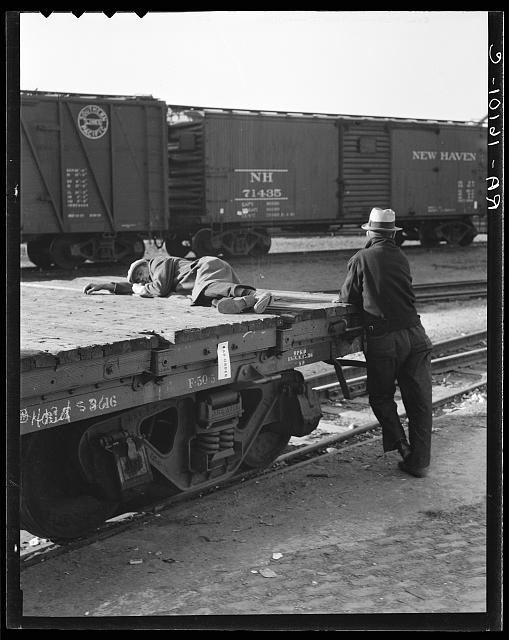

Thousands of Dust Bowl farmers and unemployed men from the Great Plains headed West during the Great Depression, creating a broad base for Upton Sinclair’s populist End Poverty in California (EPIC) plan in 1934. Photo: Dorothea Lange, Farm Security Administration

With the election just weeks away and with the Democratic candidate poised to make his surging socialist agenda a reality, business interests across the country suddenly began pouring millions of dollars into a concerted effort to defeat him. The newspapers pounced, too, with an unending barrage of negative coverage. By the time the attack ads finally reached the screens, in the new medium of staged newsreels, millions of viewers simply did not know what to believe anymore. Although the election was closer than the polls had suggested, Upton Sinclair decisively lost the 1934 race for the governorship of California.

It wasn’t until decades later that the full extent of the fraudulent smear campaign became known. As one historian observed, the remarkable race marked “the birth of the modern political campaign.”

Sinclair had made his name as a muckraker, writing best-selling books that documented social and economic conditions in 20th century America. His 1906 novel, The Jungle, exposed unsanitary conditions and the abuse of workers in Chicago’s meatpacking industry, leading to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act (and to Sinclair’s becoming a vegetarian for long periods of his life). Although President Theodore Roosevelt opposed socialism and thought Sinclair a “crackpot,” he acknowledged the importance of the author’s work, telling him that “radical action must be taken to do away with the efforts of arrogant and selfish greed on the part of the capitalist.”

Subsequent Sinclair novels targeted New York’s high society, Wall Street, the coal and oil industries, Hollywood, the press and the church; he acquired a broad spectrum of enemies. He moved from New Jersey to California in 1916 and dabbled in politics with the Socialist Party, with little success. In the throes of the Great Depression, he was struck by the abandoned factories and farms with rotting crops that dotted the California landscape and the poverty among the state’s million idled workers. “Franklin Roosevelt was casting about for ways to end it,” Sinclair later wrote. “To me the remedy was obvious. The factories were idle and the workers had no money. Let them be put to work on the state’s credit and produce goods for their own use, and set up a system of exchange by which the goods could be distributed.”

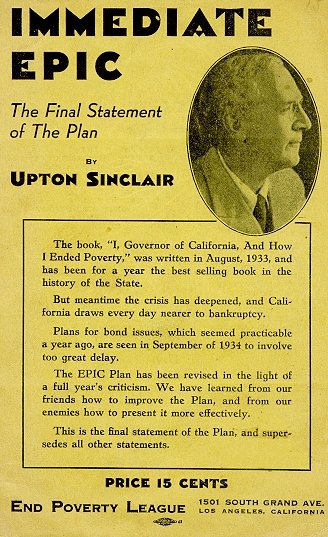

Some friends and supporters convinced him to run for office once again, but as a Democrat. In 1933 Sinclair quickly wrote a 60-page book titled I, Governor of California, And How I ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future. The cover also bore the message: “This is not just a pamphlet. This is the beginning of a Crusade. A Two-Year Plan to make over a State. To capture the Democratic primaries and use an old party for a new job. The EPIC plan: (E)nd (P)overty (I)n (C)alifornia!”

Sinclair’s EPIC plan called for the state to turn over land and factories to the unemployed, creating cooperatives that promoted “production for use, not for profit” and bartered goods and services. Appalled that the government was telling farmers to burn crops and dispose of milk while people across the country were starving, he was convinced that his program could distribute those goods and operate within the framework of capitalism.

Aside from transforming agriculture and industry, Sinclair also proposed to repeal the sales tax, raise corporate taxes and introduce a graduated income tax, which would place a larger revenue onus on the wealthy. EPIC also proposed “monthly pensions for widows, the elderly and the handicapped, as well as a tax exemption for homeowners.” Though there were similarities to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, EPIC emphasized “the democratic spirit of each individual,” as one academic observed, and called for reforms on a national level.

“There’s no excuse for poverty in a state as rich as California,” Sinclair said. “We can produce so much food that we have to dump it into our bay.”

To his great surprise, Sinclair’s book became another best-seller, with hundreds of thousands of copies circulating around the state. More than 2,000 EPIC clubs sprang around California, and they organized massive voter registration drives. Within months, Sinclair became a legitimate candidate for governor. In August of 1934, after choosing Democratic stalwart Sheridan Downey as his running mate, “Uppie and Downey” received 436,000 votes in the primary, more than all of the other candidates combined.

That result sent a shock wave throughout the state. Sinclair predicted that his candidacy and his plan would meet stiff resistance. “The whole power of vested privilege will rise against it,” he wrote. “They are afraid the plan will put into the minds of the unemployed the idea of getting access to land and machinery by the use of their ballots.”

EPIC critics were perplexed by Sinclair’s vision of working within the framework of capitalism; why, for example, would investors, as historian Walton E. Bean wrote, “buy California state bonds to finance the public enterprises that would put them out of business”? Indeed, Sinclair acknowledged that the “credit power of the state” would be used to motivate “a new system of production in which Wall Street will have no share.”

Sinclair’s opponent in the general election would be acting governor Frank Merriam, a Republican who had endured a summer of unrest as new labor laws led to strikes that were designed to test the New Deal’s commitment to organized workers. Longshoremen in San Francisco closed the port for two months. When police tried to break through the picket lines, violence broke out; two men were killed and dozens were injured. Merriam declared a state of emergency and ordered the National Guard to preserve order, but labor unions were convinced the governor had used the Guard to break the strike. A citywide protest followed, where more than a hundred thousand union workers walked off their jobs. For four days, San Francisco had become paralyzed by the general strike. Citizens began hording food and supplies.

Working quietly behind the scenes were two political consultants, Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter. They had formed Campaigns, Inc. the year before, and had already been retained by conglomerates like Pacific Gas and Electric and Standard Oil. The two consultants, like their clients, where determined to stop “Sinclairism” at any cost, and they had just two months to do it.

Newsreels footage of troops firing at so-called communist labor infiltrators led to popular fears that the New Deal had put too much power in the hands of working people, which might lead to a nationwide revolution. As the general election approached, the Los Angeles Times, led by editor Harry Chandler, began publishing stories claiming that Sinclair was a communist and an atheist. William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers spotlighted Merriam’s campaign and mocked Sinclair’s. Whitaker and Baxter fed the state’s papers erroneous but damaging Sinclair quotes, like the one spoken by a character in his 1911 novel Love’s Pilgrimage, on the sanctity of marriage, but attributed to Sinclair: “I have had such a belief… I have it no longer.” Of the 700 or so newspapers in California, not one endorsed Upton Sinclair. Merriam was advised to stay out of sight and let the negative campaigning take its toll.

Irving Thalberg, here with his wife, the actress Norma Shearer, produced the staged anti-Sinclair newsreels. Photo: Library of Congress

But nothing matched the impact of the three “newsreels” produced by Irving Thalberg, the boy wonder of the motion picture business, who partnered with Louis B. Mayer and helped create Metro Goldwyn Mayer while still in his early twenties. Mayer had vowed to do everything in his power to stop Sinclair, even threatening to support the film industry’s move to Florida if the socialist were elected governor. Like the other studios, MGM docked its employees (including stars) a day’s pay and sent the money to Merriam’s campaign.

Using stock images from past movies and interviews by an “inquiring cameraman,” Thalberg produced alleged newsreels in which actors, posing as regular citizens, delivered lines that had been written to destroy Sinclair. Some actors were portrayed as reasonable Merriam supporters, while others claiming to be for Sinclair were shown in the worst light.

“I’m going to vote for Upton Sinclair,” a man said, standing before a microphone.

“Will you tell us why?” the cameraman asked.

“Upton Sinclair is the author of the Russian government and it worked out very well there, and I think it should do here.”

A young woman said, “I just graduated from school last year and Sinclair says that our school system is rotten, and I know that this isn’t true, and I’ve been able to find a good position during this Depression and I’d like to be able to keep it.”

An African-American man added, “I’m going to vote for Merriam because I need prosperity.”

The inquiring cameraman also claimed to have interviewed more than 30 “bums” who, he claimed, were part of a wave of unemployed workers “flocking” to California because of Sinclair’s plan. Stock footage showed such “bums” hopping off packed freight trains. (Unemployed people did move to California, but did not pose the social and economic burdens implied by the newsreel.)

Greg Mitchell, author of The Campaign of the Century, wrote that the newsreels devastated Sinclair’s campaign. “People were not used to them,” Mitchell stated. “It was the birth of the modern attack ad. People weren’t used to going into a movie theater and seeing newsreels that took a real political line. They believed everything that was in the newsreels.”

Not everyone believed what they were seeing—at least not Sinclair supporters. Some of them booed and demanded refunds for having been subject to anti-Sinclair propaganda; others rioted in the theaters. After a California meeting with movie moguls, the Democratic National Committee chairman told FDR, “Everyone out there wants you to come out against Sinclair.” But Roosevelt said nothing. Sinclair sent telegrams asking for a congressional investigation of what he charged was “false” propaganda in the movie theaters.

“Whether or not you sympathize with me on my platform is beside the point,” Sinclair wrote. “If the picture industry is permitted to defeat unworthy candidates it can be used to defeat worthy candidates. If it can be used to influence voters justly, it can be used to influence voters unjustly.”

Roosevelt, worried about his New Deal program, received behind-the-scenes assurances from Merriam that he would support it. The president stayed out of the 1934 California gubernatorial campaign.

On November 6, Sinclair received 879,537 votes, about a quarter-million less than Merriam. But, as Sinclair had predicted, officeholders eventually adopted many of his positions. Roosevelt drew on EPIC’s income and corporate tax structures to support his New Deal programs. Merriam, as governor, took some of Sinclair’s tax and pension ideas (and was crushed in the 1938 election by Culbert Olson, a former EPIC leader).

Sinclair was a writer and a man of ideas, not a politician. After his bitter loss in 1934 he went back to writing, even winning a Pulitzer Prize for his 1943 novel, Dragon’s Teeth. He was never elected to a single office, but he died in 1968 as one of the most influential American voices of the 20th century.

Sources

Books: Upton Sinclair, I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future, End Poverty League, 1934. Upton Sinclair, I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, University of California Press, 1934. Greg Mitchell, The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair’s Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics, Random House, 1992/Sinclair Books, Amazon Digital Services, December 5, 2011.

Articles: “Charges Threat to Movie Folk,” Daily Boston Globe, November 1, 1934. “Eyes of Nation on California,” Daily Boston Globe, November 6, 1934. “Sinclair Charges Movie ‘Propaganda,’” Daily Boston Globe, October 29, 2934. “The Brilliant Failure of Upton Sinclair and the Epic Movement,” by John Katers, Yahoo! Voices, January 23, 2006. http://voices.yahoo.com/the-brilliant-failure-upton-sinclair-epic-15525.html?cat=37 “Dispatches From Incredible 1934 Campaign: When FDR Sold Out Upton Sinclair,” by Greg Mitchell, Huffington Post, October 31, 2010, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/greg-mitchell/dispatches-from-incredibl_b_776613.html “The Lie Factory: How Politics Became a Business,” by Jill Lepore, The New Yorker, September 24, 2012. “Upton Sinclair, Author, Dead; Crusader for Social Justice, 90,” by Alden Whitman, New York Times, November 26, 1968. “Watch: Upton Sinclair, Irving Thalberg & The Birth of the Modern Political Campaign,” by Greg Mitchell, The Nation, October 12, 2010. “On the Campaign Trail,” By Jill Lepore, The New Yorker, September 19, 2012. “Upton Sinclair,” The Historical Society of Southern California, 2009, http://www.socalhistory.org/bios/upton_sinclair.html

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)