The Spirited History of the American Bar

A new book details how the neighborhood pub, tavern, bar or saloon plays a pivotal role in United States history

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/American-bars-New-York-City-tavern-631.jpg)

Is happy hour a cornerstone of democracy? Yes, because chatting over a beer has often led to dramatic change, says Christine Sismondo, humanities lecturer at Toronto’s York University. Her new book, America Walks into a Bar, contends that local dives deserve more credit in history than they receive; they are where conversations get started. Smithsonian.com contributor Rebecca Dalzell spoke with Sismondo about her book.

How did you get interested in bars?

I used to travel around America a lot, and wherever I went it seemed that bars were important historic markers. On the Freedom Trail in Boston they talk about the Green Dragon Tavern, and in New York, George Washington said farewell to his troops at Fraunces Tavern. The American Revolution, Whisky Rebellion and Stonewall riots all came out of bars. Plus, I’ve worked in a neighborhood bar, so its function as a community center became clear to me.

What makes bars unique in American culture?

Taverns produced a particular type of public sphere in colonial America. Without them I don’t think you would have had exactly the same political landscape. Many people compare it to the coffeehouse in London or Paris salons, but those were bourgeois meeting-places. In taverns people could mix together: you see men drinking alongside the people they work for. Early laws fixed the price that tavern-keepers could charge for a drink, so they couldn’t cater to wealthy patrons. And once you add alcohol in there, it changes the way everyone relates to each other. You end up with accelerated relationships—and occasionally cantankerous ones. People become more willing to go out and raise hell over things that they might have let go when sober.

Are there any constants that run through our bar history?

Bars have always been where people share news and discuss it. And there’s an unwritten code in most neighborhood bars that people are supposed to check their degrees at the door. You can find a lawyer, university professor, taxi driver and dishwasher all talking about politics, and nobody’s supposed to pull rank.

How have bars evolved over time?

From colonial times to the mid-19th century you had taverns, which provided food and lodging. They had a tapster in a cage—as opposed to at a long bar—and it was open to all members of the community, including women and children. Then you start to see the dedicated saloon, which didn’t necessarily serve food, and mixed cordials and spirits at a long bar. Women were rarely allowed. Hotel bars existed on the high end, catering to business travelers. During Prohibition there were speakeasies, and after that people went back to the term tavern, though it was more like the old saloon. Now of course we call bars all of the above.

What’s an event that could only have happened in a bar?

New York’s Stonewall riots in 1969. They didn’t come out of nowhere as people often think. Since bars were the only places where gay people could congregate, everyone got to know each other. During the McCarthy era the police regularly shut the bars down, denying gays of their fundamental right to associate. When they’d had enough and it came time to organize, the networks were already in place through the bars.

Have reformers always tried to control drinking in America?

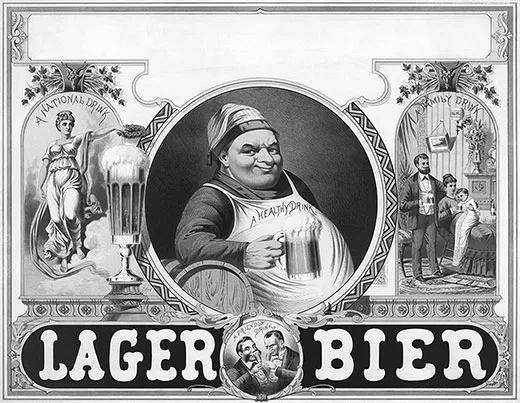

Alcohol was accepted for a long time—actually considered a panacea, what you drank if you were sick or didn’t have bread. You were a well-behaved Puritan if you had a drink at breakfast. It only became identified as a problem, something you should give up to save your soul, in the mid-19th century, with reformers like Lyman Beecher and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

And this led to Prohibition?

I actually don’t think that moral questions had much to do with the passage of Prohibition. It seemed to be largely about criminalizing the saloon as opposed to alcohol, indicated by the fact that it was still legal to possess alcohol. You just couldn’t sell or distribute it. The most powerful group in the 40 years before Prohibition wasn’t the WCTU but the Anti-Saloon League, which made the saloon the main culprit, not alcohol. Industrialists followed, saying yes, if we control the saloon we’ll have fewer people agitating for labor, campaigning for social reform and coming in to work hung over. While the WCTU was important for getting the movement started, it was run by women, who didn’t have a lot of power. People didn’t jump on board with Prohibition until they saw the saloon as a dangerous, radical political space.

Was there a double standard by which bars were policed?

Absolutely. A lot of racial and religious intolerance played into it. Laws shutting taverns on Sunday in the 1850s are the worst example, because they targeted immigrants. Taverns were the only recreational space they had access to and Sunday was the only day they had off. But city governments, especially in Chicago, wanted to stifle the machine politics of the immigrant taverns. During Prohibition, the chasm between working-class and respectable drinking places was even clearer—the law wasn’t enforced equally.

What was speakeasy culture like during Prohibition?

There were fewer people visiting speakeasies than is commonly believed. Going out was equivalent to bottle clubs now, where people pay $600 for a liter of vodka—it was a high-end, sophisticated culture. If you could afford it, it was fun and interesting, especially because women started mixing in. But the majority just couldn’t pay the inflated price of alcohol. They either couldn’t afford to drink at all or could only afford to drink very dangerous forms of alcohol. Yes, there were those who drank as though there was no Prohibition, but that’s a smaller segment of the population than people think.

Is there anyone who deserves the most credit in history for defending bar culture?

In terms of bar history, we don’t think of Clarence Darrow as much of a character, but he was really important in trying to defend the saloon from its detractors in the years around Prohibition. H.L. Mencken gets all the credit, but Darrow was an important part of that. Mencken defends it primarily on libertarian grounds, in terms of personal freedom. Darrow pointed out that the Anti-Saloon League had racist and class motives. He defended the saloon as a gathering place for minorities and people with radical ideas. He has a great quote that not every Anti-Saloon Leaguer is a Ku Klux Klanner, but every Ku Klux Klanner is an Anti-Saloon Leaguer.

What are some surprising things that used to happen in bars?

In some bars on the Bowery in New York City, they did away with glassware and for three cents you were allowed to drink all you could through a tube until you took a breath. So people would be outside practicing holding their breath. There was also dodgy entertainment. Freak shows traveled through in the 18th century, with animals preserved in formaldehyde, and later they’d have sports like wrestling or watching terriers kill rats.

Who’s your favorite bartender?

I like Orsamus Willard, who worked at New York’s City Hotel in the 1840s. He was famous for his peach brandy punch, and was the first bartender to get mentioned in newspapers. He had a tireless devotion to service and an incredible memory, never forgetting anyone’s name or favorite room. Once there was a guest who left abruptly because his son was ill. When he returned five years later, Willard asked after his son’s health and gave him his old room.

Can you recommend some memorable bars?

A fantastic one in New Orleans is the Hotel Monteleone’s Carousel Bar, because the bar really rotates. It used to be a literary hangout—Tennessee Williams went there. Henry Clay introduced the mint julep at the Willard [Hotel]’s Round Robin Bar in Washington, which has always been important in politics. In New York, I love the King Cole Bar in New York’s St. Regis Hotel. It’s hard not to think of that immediately because of the sheer beauty of the bar, which has a Maxfield Parrish mural, and the incredibly expensive cocktails. Downtown, McSorley’s Old Ale House is great because it hasn’t really changed in over 100 years.