The Shark Attacks That Were the Inspiration for Jaws

One rogue shark. Five victims. A mysterious threat. And the era of the killer great white was born

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/EveningLedger-SharkAttack-631.jpg)

In the summer of 1916, panic struck the Jersey Shore. A shark sunk its teeth into Charles Vansant, the 25-year-old son of a Philadelphia businessman, out for an evening swim in the resort town of Beach Haven on July 1. A lifeguard pulled him ashore, but he quickly bled to death. Five days later, and 45 miles to the north, in Spring Lake, New Jersey, Charles Bruder, a young bellhop at a local hotel, met a similar fate.

Then, something even stranger happened. The rogue great white traveled 30 miles north of Spring Lake and into Matawan Creek. On July 12, Lester Stillwell, 11, was playing in the creek 16 miles inland when the shark attacked. A young man named Watson Stanley Fisher attempted to save the boy, but was fatally injured in the process.

Joseph Dunn was luckier. The teenager, the shark’s fifth victim, was bitten in the creek less than a half-hour later and survived.

The shark’s ferocious spree is said to have served as inspiration for Jaws—both Peter Benchley’s novel and Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster film. (Update: In 2001, however, Benchley denied the connection in a correction to a New York Times article.) Ichthyologist George Burgess calls it the “most unique set of shark attacks that ever have occurred.”

He would know. As curator of the International Shark Attack File, kept at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, Burgess is an expert on shark attacks. He presides over the archive, which includes case files for more than 5,000 attacks that occurred from the 16th century up to today. When a shark strikes somewhere in the world, as one did in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, two weeks ago, Burgess and his colleagues “investigate much like a detective would investigate a crime.” They interview the victim and any witnesses, collect medical records and study photographs of the wounds to determine the size and perhaps the species of shark responsible.

I recently spoke with Burgess about the circumstances surrounding the historic attacks of 1916.

From the records that exist, what is your sense of how the general public reacted to the attacks?

I see a common pattern around the world. When shark attacks occur, there is obviously shock. Then, the second phase is denial—denial that it was done by a shark. It has to be done by something else. The third phase is the feeling that if we shuffle it under the rug, maybe it will disappear. The fourth phase is realizing that none of those things are working and that we probably need to go kill some sharks. Then, in the fifth phase, the reality sets in, finally, that that’s not the solution and we probably ought to bring in a scientist that knows what’s going on. The phases they went through in New Jersey were the same.

These days, there is more of a level view of sharks. Back then, this was brand-new and terror-driven. In 1916, the rallying cry was “Let’s go kill some sharks!”

People didn’t even know what predator caused the attacks at first, though, right? What were some of the theories?

The thinking was it couldn’t be a shark, because we don’t have sharks here. It must be a sea turtle. Someone suggested it was a school of turtles that was coming in and biting things. Of course, turtles don’t school, and they don’t bite human beings, but it sounded good. A killer whale was suggested as well. The theories abounded and were allowed to get out unchecked into the media simply because there was not a forceful scientific authority that really knew what was going on to step right in and try to level the conversation.

There were a few scientists, regarded as experts, who weighed in.

John Treadwell Nichols was a well-known ichthyologist at the American Museum of Natural History. He knew something about sharks. Then, there was the director of the New York Aquarium, Charles Haskins Townsend, who was a good ichthyologist as well. He knew his sharks and dealt with them in an aquarium. Robert Cushman Murphy, another American Museum of Natural History guy, was working with sharks in Long Island and knew something about what sharks were there and when.

What were these scientists saying?

They very accurately portrayed the suite of species that were found in the area. They knew some of the timing of when the species appeared. So, they went through the checklist the same way I did, frankly, with a bunch of media calling me about the recent Cape Cod attack.

I said, look, here are basically the four species you are likely to see in this area. These two species are basically offshore species, and they only occasionally will wander into near-shore waters. You can probably eliminate those two. This one here is a ground shark that lives on the bottom and is not known to attack humans. We can probably eliminate that one. That means that your most logical one is this species.

They were doing that same kind of thing. One of them suggested that the white shark was the most likely candidate based on his knowledge of the sharks of the area and the habits of the shark.

How would you describe scientists’ knowledge of sharks at the time?

Very poor. Back in those days, sharks were basically unknown. There was little known about what was going on in terms of their movement patterns and their ecology. There were a lot of preconceptions out there that were quite erroneous, particularly in the public sector where the only source of information was anecdotal stories, newspapers and books, which usually portrayed the sharks in a negative way.

Historically, money went to study those animals that were economically most important. There has always been money put into salmon, and there is money put into tuna and cod. Sharks, by contrast, never had a market per se and, in fact, had just the opposite. They were eating these important food fishes and were therefore not only of no concern from a management standpoint but something we really didn’t want to have around. Those darn things are eating the good fish! As a result, research on sharks lagged far behind that of other fishes all the way until the 1990s.

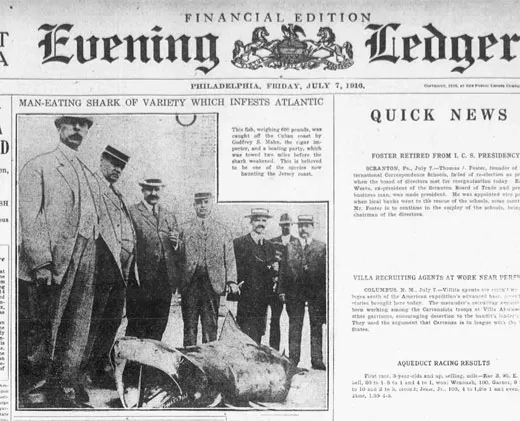

In newspaper accounts of the 1916 attacks, the shark is referred to as a “sea monster” and a “sea wolf.”

Exactly. It is unfortunate when we still see remnants of that today. I’ll have a little game with you. You drink a beer every time you hear the expression “shark-infested waters.” See how drunk you get. Whenever a boat goes down or an airplane goes down, we hear that kind of thing. I correct folks all the time. Sharks don’t infest waters, they live in them. Lice infest; they are parasites. There is still bias in that sort of thought process today.

What drew the shark close to shore for the attacks?

One of the most popular theories was one that we hear today. That is, there is not enough fish for the sharks to eat, so therefore they are going to eat humans. The people who are most likely to say it today are sport fishermen, who aren’t catching the same amount or the same size fish that they once did. Back in 1916, it was commercial fishermen who were saying it. It’s not a real defensible argument.

There was a guy who wrote in to the editor of the New York Times saying that these sharks were following U-boats across from the Eastern Atlantic. It was almost an implication that it was a German plot. The world was at war in Europe and the anti-German sentiment was high. All kinds of strange things.

Although it is hard to go back in time and always dangerous to make analogies like this, it could have been a shark that was either injured or had some sort of deformity. It became a deranged killer. We know, for instance, that lions or elephants, with injuries to their feet or a rotten tooth, have sometimes been implicated in attacks on humans because they are feeling pain from these other things. A same kind of thing can occur in a white shark. It is very unusual for sharks though. We don’t have very many instances in all of our studies on sharks where we can attribute multiple attacks to a single individual, the so-called rogue shark. That theory was in vogue in the 1950s as a result of a researcher in Australia who pushed it, but it fell by the wayside since then, and the general feeling is that shark attacks are one-off kind of events.

What actions were taken in these New Jersey towns after the string of attacks began?

On the coast, many communities put up fences around their beaches. Other communities put up money or rewards to people who could bring in sharks—so much a head per shark, which prompted a bunch of fishermen to go out and fish. Shark fishing became the rage. One of the newspapers declared it a new sport. It is like what happened when the book and the movie Jaws came out in the 1970s. It spawned a huge upswing in recreational fishing for sharks with fishing tournaments. There was this collective testosterone rush that occurred on the East Coast of the United States following those events because every guy wanted to go out and catch a shark, have his picture taken with his foot on the head of a shark and have a shark jaw hanging up in his house.

The rogue shark was ultimately caught, right?

The final story was that a white shark was caught nearby. According to the newspapers of the time, it yielded body parts of two of the victims from Matawan Creek. The shark itself was put on display in somebody’s shop in New York and yielded a nice dividend of money for the owner, who charged so much per head to see it.

The question we at the International Shark Attack File have is, how good was the report that the animal was, one, a white shark and, two, really had human remains that could be identified as those two people? Of course, we don’t have the benefit of the kinds of things we would have today, such as good photographs of that shark. We could have used photographs to confirm the species. Also, there was no coroner’s report to prove the human remains part. All we can do is believe what was said in the press at the time. The press identified it as a white shark.

Did the 1916 shark attacks inspire Peter Benchley’s Jaws?

Certainly, Benchley was aware of the 1916 stuff. As part of his book, he had done some looking back at the attacks. It was inspirational to him in terms of getting the feeling of the social terror. The first Jaws movie was a masterpiece in capturing those feelings.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)