The Godfather of Extreme Skiing

Meet Yuichiro Miura, the man who skied down Mt. Everest more than 50 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Extreme-Skiing-631.jpg)

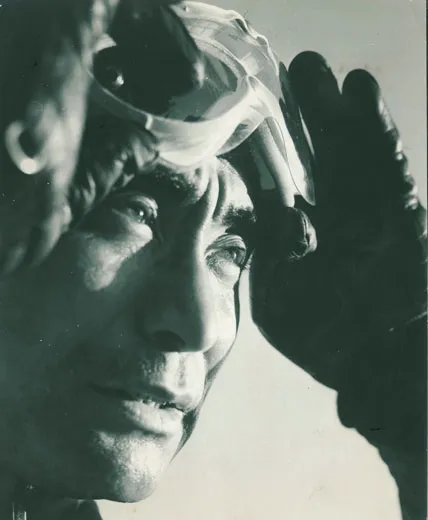

On the afternoon of May 6, 1970, Yuichiro Miura stood on Mount Everest’s South Col, at an altitude of more than 26,000 feet. On his lips he wore white sun block, and on his head a fighter pilot’s helmet, complete with a transceiver. He also had oxygen tanks, and a parachute was strapped to his back, though no one knew if the parachute would work at that altitude. On his feet he wore skis.

Breathing quickly and deeply, Miura reached a state of Mu, a Zen-like feeling of nothingness.

Then he took off.

***

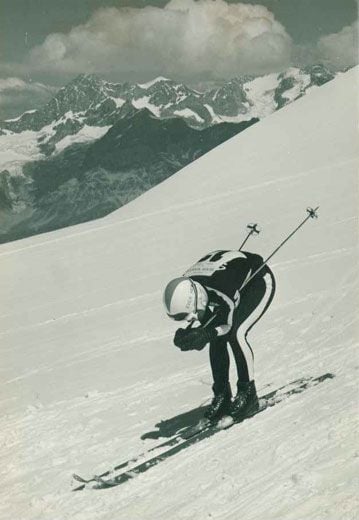

Miura had a reputation in skiing circles before he ever set foot on Everest. The son of the legendary Keizo Miura, who pioneered skiing in Japan’s Hakkōda Mountains, he set a world speed skiing record of 172.084 kilometers per hour (nearly 107 miles per hour) in 1964. “It was a wonderful feeling that I was able to set the record,” Miura says, “but I knew the record was meant to be broken.”

Broken it was, the very next day. Miura never reclaimed it, but instead made a name for himself by skiing the world’s most spectacular summits, starting with Japan’s Mount Fuji in April 1966. He wanted to schuss down Fuji as fast as possible, but he also wanted to live. So Miura decided to deploy a parachute when he reached his maximum velocity, on the theory that it would allow him to slow down to safety. His innovation worked … at about 93 miles per hour. He became the first person to ski that mountain.

Miura also skied Mount Kosciusko, the highest peak in Australia, later that year, and Mount McKinley, the highest peak in North America, in 1967. The next year, he became the first person to ski Mexico’s Mount Popocatépetl, and in 1969, he added Chile’s Towers of Paine to his list of firsts. “It seems to me that greater than the satisfaction of winning in competition,” Miura later wrote of his decision to pursue big mountain riding, “is the joy of forgetting yourself and becoming one with the mountains.”

After Miura’s feat on Fuji, New Zealand’s Tourism Bureau invited him to ski the Tasman Glacier. While in New Zealand, he met Sir Edmund Hillary, the climber who teamed with Tenzing Norgay to conquer Mount Everest’s summit in 1953. “Sir Edmund Hillary was my superhero,” Miura says. “When I listened to his Everest summit, I determined my target to be Everest, too.” After the shock of someone contemplating skiing Everest wore off, Hillary actually encouraged him. “He inspired me to be an extreme skier who can make history,” Miura says.

The Nepalese government turned out to be receptive to the idea, too. But there was a catch—Miura would be allowed to ski not Everest’s summit, but the South Col. The col is the slightly lower pass connecting Everest and Lhotse, the world’s fourth-tallest mountain, but still, it slopes at 40 to 45 degrees. “My objective was clear, that was to ski down Everest,” he says. “I did not really care about the summit at that time.”

As he scouted and made test runs on Everest during the fall of 1969, Miura was forced to come to terms with a highly probable outcome. “When I planned to ski Everest, the first thing I faced was ‘How can I return alive?’ ” he recalls. “All the preparation and training was based on this question. But the more I prepared, I knew the chance of survival was very slim. Nobody in the world had done this before, so I told myself that I must face death. Otherwise, I am not eligible.”

In February 1970, the Japanese Mount Everest Ski Expedition arrived in Katmandu. As much a scientific mission as an extreme skiing adventure, the squad included mountaineers, scientists, a ski team, a film crew, photographers and members of the press. It took 800 porters to carry 27 tons of equipment to the Everest base camp, a 185-mile, 22-day journey that began on March 6, 1970.

At base camp, the expedition spent several weeks acclimatizing to Everest’s thin air—at 17,600 feet, its oxygen content is about half that of sea-level air—and preparing for further mountain treks. For his part, Miura made Everest into his personal backcountry ski resort, conducting numerous test runs, with and without a parachute, often riding the virgin slopes with childlike glee.

The adventure, however, was not without cost. Two people suffered fatal heart attacks in the thin air, and a cave-in on the Khumbu Icefall claimed the lives of six Sherpas. “For a moment I thought of stopping the expedition,” Miura recalls. “But later, I felt in order to meet their sacrifice, I must not run away. To pay back the respect to them, I felt it was my responsibility to face the challenge and complete it.”

At 9 a.m. on May 6, 1970, Miura made a few wide turns on the South Col’s slopes. He thus became the first person to ski at an altitude higher than 26,000 feet. Miura hiked to the starting point for a long run down the South Col, and after getting the logistics set up for filming and rescue, he was ready to go at 11 a.m. The winds, however, were too strong. If they didn’t abate, Miura would have to return to lower elevations, and it would be at least a week before he could try again.

But the winds died down and at 1:07 p.m. the 37-year old skier started his descent in earnest.

***

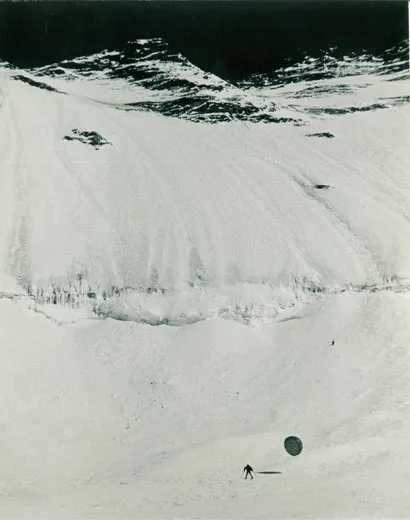

Sailing down the col’s bumpy blue ice, Miura quickly deployed his parachute. “When it opened I felt I was lifted,” he says. “However, the strong turbulence, the direction of wind and its strength were constantly changing, so it was very hard to keep the balance.” The parachute became worthless, and Miura couldn’t maintain control.

As his skis chattered across the rough ice, he used every technique he knew to slow down—and failed. Then a ski caught on a rock and he fell. As he slid helplessly down the ice, he could feel the cold on his spine.

“I was 99 percent sure I would not survive,” he says. “Death was not a particular feeling, but rather I was thinking [about] what I would be after 3,000, 30,000 or 3 million years in the future, my reincarnation. ”

Miura’s skis released, but the safety straps kept them attached to his body; they flailed beside him until one broke off and bounced like a toothpick. He tried to grab onto the ice, but there was nothing he could do to stop as he slid toward the world’s largest bergschrund, or crevasse, waiting below. After sailing over a rock, which propelled him 33 feet into the air, he hit a small snow patch and miraculously halted, just 250 feet from the bergschrund.

“ ‘Am I live or dead? Which world I am in?’ ” he recalls thinking. “After about a minute, I realized that I am alive. I felt that I returned to this world in the form of human, as Yuichiro Miura. Like the soul returning to the body.”

***

The entire descent, approximately 4,200 vertical feet, took about 2 minutes and 20 seconds. Miura’s journey was recorded in the 1975 documentary The Man Who Skied Down Everest, the first sports film to win an Academy Award for best documentary. He also wrote a book by the same title, published in 1978.

Miura’s legend was secure, but there were more summits to conquer. In 1981, he skied Africa’s Mount Kilimanjaro, and in 1983 he became the first person to ski Antarctica’s Mount Vinson. In 1985, he added Russia’s Mount Elbrus and Argentina’s Mt. Aconcagua to his bucket list. “After I skied from Everest, I thought my Everest challenge is over,” he says. “I had more interest in skiing from the highest peaks of the seven continents. I did not imagine myself climbing the peak later in life.”

Yet…in the late 1990s, Miura set his sites on climbing Everest. After years of preparation, he reached the summit on May 22, 2003, at the tender age of 70 years and 223 days. At the time, he was the oldest person to summit the mountain. Five years later, he reached the summit again. Both times he beheld the South Col, and both times he thought: “How could I ever done it and survived?”

He’s planning to summit Everest again in 2013, this time from the Chinese/Tibetan side. He would be 80.