The Doomed South Pole Voyage’s Remaining Photographs

A 1912 photograph proves explorer Captain Robert Scott reached the South Pole—but wasn’t the first

“Great God!” British Capt. Robert Falcon Scott wrote in his journal on January 17, 1912, the day he reached the South Pole. He was not exultant. “This is an awful place,” he went on, “and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.”

For more than two months, Scott and his men had hauled their supply sledges across 800 miles of ice from their base camp at Antarctica’s McMurdo Sound, hoping to become the first people to reach the pole. But the photograph at left, taken by Lt. Henry Bowers the same day, makes clear the reason for Scott’s despair: The Norwegian flag flying above the tent had been left by the explorer Roald Amundsen, whose party had arrived five weeks earlier. Inside the tent, Scott’s men found a letter Amundsen had written to Haakon VII, king of Norway, along with a note asking Scott to deliver it for him.

Even if you don’t know what came next, Bowers’ photograph conveys a sense of failure. The men show no arm-in-arm camaraderie. Their faces are weather-beaten. No supplies are visible. In fact, Scott and the four men he brought with him on the last 150-mile dash to the pole were running low on food and fuel. (Bowers had been added at the last minute, dangerously stretching their rations.) Their return trip would become one of the most dismal failures in the annals of polar exploration.

In the late Antarctic summer, the men encountered unusually cold temperatures of minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and blizzards kept them tent-bound for days on end. Petty Officer Edgar Evans died on February 17, probably from a head injury sustained in a fall into a crevasse. As resources ran low, Capt. Lawrence Oates famously sacrificed himself: Crippled by frostbite, he left the party’s tent during a March 16 snowstorm with the words, “I am just going outside and may be some time.”

The following November, a search party came upon Scott’s last camp, a mere 11 miles from a cache of supplies. Inside a tent were the bodies of Scott, Bowers and Edward A. Wilson, the expedition’s chief scientist. Scott’s journals were there too, with the last entry dated March 29, along with 35 pounds of geological specimens carried at great cost and Bowers’ undeveloped film. David M. Wilson, a descendant of Edward Wilson and author of the recently published The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott, says Bowers’ pictures proved that both Scott and Amundsen had reached the pole.

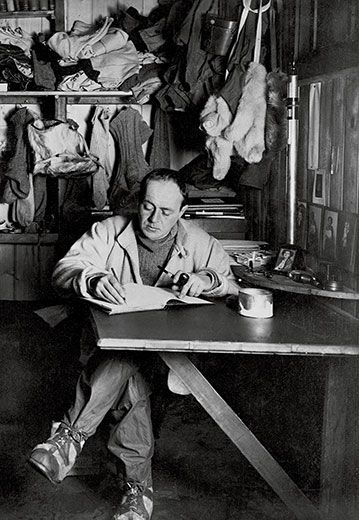

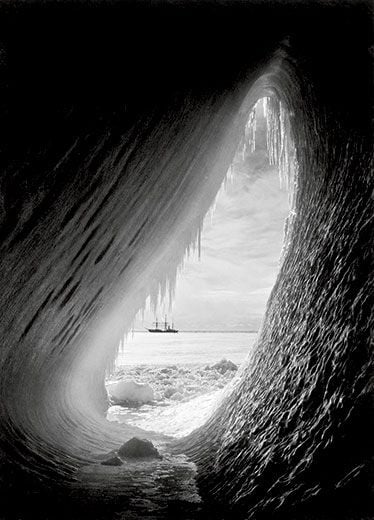

Bowers’ straightforward work contrasts with that of Herbert Ponting, the photojournalist Scott had hired to document his expedition. Ponting had traveled extensively in Asia and sold his work to prominent London magazines, and the Scott assignment made him the first professional photographer to work in the Antarctic. The image on this page shows Ponting’s artistry: It captures the textures of ice, water and cloud in a perfectly balanced composition, with Scott’s ship, Terra Nova, in the background. Scott described the scene in terms that suggest his own sensitivity to art and nature: “It was really a sort of crevasse in a tilted berg parallel to the original surface....Through the larger entrance could be seen, also partly through icicles, the ship, the Western Mountains, and a lilac sky.”

Ponting did not accompany Scott to the pole—among other things, his equipment was considered too heavy. As planned, he left Antarctica for England in February 1912, while Scott and his men were still struggling to make it home. At first, the news of Scott’s fate overshadowed Ponting’s pictures, but after World War I the photographer published his work, to great acclaim, in a book titled The Great White South. “All subsequent Antarctic photography,” Wilson wrote to me in an e-mail, “is a footnote to his pioneering work.”

Taken together, the two images reflect the two poles of Scott’s expedition; despite the tragedy, the words and images Scott and his men left behind became a lasting legacy to science and art. As Scott noted in his final diary entry, “these rough notes and our dead bodies” would tell his tale. Amundsen planted the flag, but it was Scott who captured our imagination.

Victoria Olsen last wrote for Smithsonian about the photographs of Frances Benjamin Johnston.