The Brink of War

One hundred fifty years ago, the U.S. Army marched into Utah prepared to battle Brigham Young and his Mormon militia

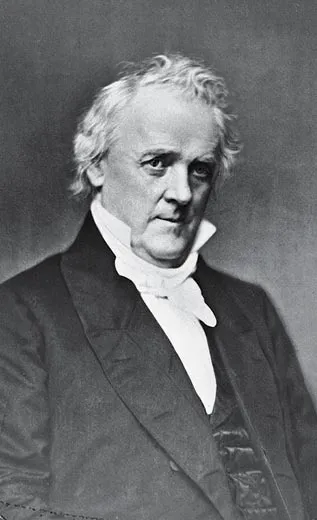

On July 24, 1847, a wagon rolled out of a canyon and gave Brigham Young, president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, his first glimpse of the Great Salt Lake Valley. That swath of wilderness would become the new Zion for the Mormons, a church roughly 35,000 strong at the time. "If the people of the United States will let us alone for ten years," Young would recall saying that day, "we will ask no odds of them." Ten years to the day later, when the church's membership had grown to about 55,000, Young delivered alarming news: President James Buchanan had ordered federal troops to march on the Utah Territory.

By then, Brigham Young had been governor of the territory for seven years, and he had run it as a theocracy, giving church doctrines precedence in civil affairs. The federal troops were escorting a non-Mormon Indian agent named Alfred E. Cumming to replace Young as governor and enforce federal law. In their long search for a place to settle, Mormons had endured disastrous confrontations with secular authorities. But this was the first time they faced the prospect of fighting the U.S. Army.

On June 26, 1858, one hundred fifty years ago this month, a U.S. Army expeditionary force marched through Salt Lake City—at the denouement of the so-called Utah War. But there was no war, at least not in the sense of armies pitched in battle; negotiators settled it before U.S. troops and Utah militiamen faced off. On June 19, the New York Herald summarized the non-engagement: "Killed, none; wounded, none; fooled, everybody."

In retrospect, such glibness seems out of place. The Utah War culminated a decade of rising hostility between Mormons and the federal government over issues ranging from governance and land ownership to plural marriage and Indian affairs, during which both Mormons and non-Mormons endured violence and privation. The tension was reflected in the fledgling Republican Party's 1856 presidential platform, which included a pledge to eradicate the "twin relics of barbarism—polygamy and slavery." To look back at this episode now is to see the nation at the brink of civil war in 1857 and 1858—only to pull back.

"The Utah War was catastrophic for those who suffered or died during it, and it was catalytic in advancing Utah along the slow but eventual path to statehood," says Richard E. Turley Jr., assistant church historian and recorder of the LDS Church.

Allan Kent Powell, managing editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly, notes that Abraham Lincoln warned, in 1858, that "a house divided against itself cannot stand," referring to the United States and slavery. "The same comment could have been applied to Utah," says Powell. "Just as the nation had to deal with the issue of slavery to ensure its continuation, so did the Territory of Utah have to come to an understanding and acceptance of its relationship with the rest of the nation."

The nation was unable to put off its reckoning over slavery. But the resolution of the Utah War bought the LDS Church time, during which it evolved as a faith—renouncing polygamy in 1890, for example, to smooth the way to Utah statehood—to become the largest home-grown religion in American history, now numbering nearly 13 million members, including such prominent Americans as Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah, Senate majority leader Harry Reid of Nevada and hotelier J. W. Marriott Jr. At the same time, anti-Mormon bias persists. Last December, in an effort to make voters more comfortable with his Mormon faith, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, then a Republican presidential contender, declared like the Catholic John F. Kennedy before him: "I am an American running for president. I do not define my candidacy by my religion." In a Gallup Poll taken after Romney's speech, 17 percent of respondents said they would never vote for a Mormon. Roughly the same percentage answered similarly when Romney's father, Michigan Governor George Romney, ran for president in 1968.

Even now, issues rooted in the era of the Utah War linger. Last September, when the LDS Church formally expressed regret for the massacre of some 120 unarmed members of a wagon train passing through Utah on September 11, 1857, the Salt Lake Tribune published a letter comparing the events to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. A raid this past April by state authorities on a fundamentalist Mormon compound in Texas returned the subject of polygamy to the headlines (though the sect involved broke from the LDS Church more than 70 years ago).

"In the late 1850s, Mormons believed that the world would end within their lifetimes," says historian David Bigler, author of Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West, 1847-1896. In addition, he says, "they believed the forefathers who wrote the American Constitution had been inspired by God to establish a place where His kingdom would be restored to power. The Mormons believed their own kingdom would ultimately have dominion over all the United States." At the same time, the American nation was pursuing a "manifest destiny" to extend its domain westward all the way to the Pacific. The continent was not large enough to accommodate both beliefs.

The conflict had been building almost from the moment Joseph Smith, a religious seeker, founded his church in Palmyra, New York, in 1830. Where other Christian churches had strayed, Smith preached, the LDS Church would restore the faith as conceived by Jesus Christ, whose return was imminent. The next year, Smith moved with about 75 congregants to Ohio and sent an advance party to Missouri to establish what they believed would be a new Zion.

In the agrarian democracy Americans were building, both land and votes mattered. Non-Mormons felt threatened by the Mormons' practices of settling in concentrated numbers and voting as a bloc. The Missouri Mormons were forced to relocate twice in the mid-1830s. In Ohio, an anti-Mormon mob tarred and feathered Smith in 1832, and he left the state in 1838 after civil lawsuits and a charge of bank fraud followed the failure of a bank he had founded. By the time he arrived in Missouri that January, non-Mormons were assaulting Mormons and raiding their settlements; a secret Mormon group called the Sons of Dan, or Danites, responded in kind. That August, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an order to his state militia directing that the Mormons "be exterminated or driven from the State for the public peace." Two months later, 17 Mormons were killed in a vigilante action at a settlement called Haun's Mill.

The Mormons moved next to Illinois, founding the town of Nauvoo there in 1840 under a charter that gave the city council (which Smith controlled) authority over local courts and militia. This settlement grew to about 15,000 people, making it the biggest population center in the state. But in 1844, authorities jailed Smith in the town of Carthage after he destroyed a Nauvoo newspaper that had alleged he was mismanaging the town and had more than one wife. At that point, Smith's polygamy was acknowledged only to the LDS Church's senior leaders. In a raid on the jail, an anti-Mormon mob shot the church founder to death. He was 38.

"Few episodes in American religious history parallel the barbarism of the anti-Mormon persecutions," historian Fawn Brodie wrote in her 1945 biography of Smith. At the same time, she added, the early Mormons' relationships with outsiders were characterized by "self-righteousness" and an "unwillingness to mingle with the world." To non-Mormons in Illinois, Brodie wrote, "the Nauvoo theocracy was a malignant tyranny that was spreading as swiftly and dangerously as a Mississippi flood." Amid continuing harassment in Illinois, the Mormons prepared to leave.

After Smith's death, the LDS Church's ruling council, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, took control of church affairs. The lead apostle, Brigham Young, a carpenter from Vermont and an early convert to Mormonism, eventually succeeded Smith. In February 1846, he led the beginnings of an exodus of some 12,000 Mormons from Illinois, determined to establish their faith beyond the reach of American laws and resentment. Brigham Young biographer Leonard J. Arrington has written that Young and other church leaders knew about the Great Salt Lake Valley from trappers' journals, explorers' reports and interviews with travelers familiar with the region.

At the time, most of what would become the American Southwest belonged to Mexico, but Young believed that that nation's hold on its northern frontier was so tenuous that the Mormons could settle there free from interference. In the spring of 1847, he led an advance party of 147 from an encampment in Nebraska to the Great Salt Lake Valley, arriving that July. Over the next two decades, some 70,000 Mormons would follow; the grueling journey would be one of the defining experiences of the LDS Church.

In February 1848, Mexico sealed its defeat in the Mexican-American War by signing the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ceding to the United States what is now California, Nevada, Utah, Texas and parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Wyoming. Just six months after arriving in their new Zion, the Mormons found themselves back under the authority of the United States.

To preserve self-rule, church leaders quickly sought official status, petitioning Congress in 1849 first for territorial status, then for statehood. The land they sought was vast, running from the Rockies to the Sierra Nevada and from the new border with Mexico all the way to present-day Oregon. Congress, guided in part by the struggle between forces opposing and condoning slavery, designated a Utah Territory, but not before reducing the area to present-day Utah, Nevada, western Colorado and southwestern Wyoming.

Territorial status gave the federal government greater authority over Utah affairs than statehood would have. But President Millard Fillmore inadvertently set the stage for a clash with his choice for the new territory's chief executive. In 1850, acting partly in response to lobbying from a lawyer named Thomas L. Kane, a non-Mormon who had advised Mormon leaders in previous ordeals, Fillmore named Brigham Young governor of the new Utah Territory.

Young ran the Utah Territory much as Smith had run Nauvoo, and conflicts between religious and secular authorities soon re-emerged. The Mormon leaders were suspicious of both the character and intent of federal appointees, such as a judge who was found to have abandoned his wife and children in Illinois and brought a prostitute to Utah. And over the next seven years, a succession of federal officers—judges, Indian agents, surveyors—came to the territory only to find that the governor would circumvent or reverse their decisions.

Young "has been so much in the habit of exercising his will which is supreme here, that no one will dare oppose anything he may say or do," Indian agent Jacob Holeman wrote to his superior in Washington, D.C. in 1851—in effect going over Young's head (Young was also the territory's superintendent of Indian affairs). Surveyor General David Burr reported that Young told him federal surveyors "shall not be suffered to trespass" on Mormon lands. Through the mid-1850s, federal appointees returned East frustrated or intimidated or both, and some of them wrote books or articles about their travails. Anti-Mormon sentiment spread, inflamed particularly by reports of polygamy.

By then, the practice of plural marriage had expanded beyond Joseph Smith's inner circle, and word of it had been passed by non-Mormon emigrants passing through Utah, where the evidence was in plain view. "During the first few years after their arrival in Utah," writes Young biographer M. R. Werner, "the fact that the Mormons practiced polygamy was an open secret."

The Mormons' embrace of plural marriage was based on a revelation that Smith said he had received. (It was written down in 1843, but most historians agree that Smith had begun taking multiple wives earlier.) With the example of polygamous biblical patriarchs such as Abraham and Jacob in mind, Smith concluded that "the possession of more than one wife was not only permissible, but actually necessary for complete salvation," Werner writes. Brigham Young, who took his first plural wife in 1842, after 18 years of monogamy, maintained that he had been a reluctant convert: "I was not desirous of shrinking from any duty, nor of failing in the least to do as I was commanded," he wrote in a reminiscence that would be collected in the church compendium Journal of Discourses, "but it was the first time in my life that I had desired the grave." (By the time he died, at age 76 in 1877, he had taken 55 wives but shared no "earthly life" with 30 of them, according to Arrington.) For years Young and other church leaders had dismissed allegations of plural marriages as calumnies circulated by enemies, but by the early 1850s, such denials were no longer plausible.

On August 29, 1852, at a general conference of Mormons in Salt Lake City, the church leadership publicly acknowledged plural marriage for the first time. Orson Pratt, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, delivered a lengthy discourse, inviting the members to "look upon Abraham's blessings as your own, for the Lord blessed him with a promise of seed as numerous as the sand upon the seashore." After Pratt finished, Young read aloud Smith's revelation on plural marriage.

The disclosure was widely reported outside the church, and the effect was to quash any hopes the Utah Territory might have had for statehood under Young's leadership. And conflicts between Young's roles as governor of the territory and president of the church would only become more complicated.

In April 1855, at the Mormons' spring conference, Young called on some 160 men to abandon home, farm and family and head into the wilderness surrounding the Utah settlements to establish missions among the Native Americans there.

In Mormon cosmology, Indians were the descendants of a fallen ancient patriarch, and church officials said they were undertaking the missions to convert tribes on their borders to their faith and to improve their welfare. But Garland Hurt, recently arrived in Utah as an Indian agent, was suspicious. In a confidential letter to the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, he wrote that the missions were actually intended to teach the Indians to distinguish between "Mormons" and "Americans"—a distinction, he added, that would be "prejudicial to the interests of the latter." The few historians who have studied these three missions disagree over their purpose. But irrespective of Young's intentions, correspondence to and from the missionaries, held in LDS archives, reflects rising tension between Mormons and the non-Mormon world.

The first of the missionaries left Salt Lake City in May 1855. One band of men rode more than 350 miles north, into what is now Idaho—beyond Young's legal jurisdiction. Another headed 400 miles southwest—again, beyond Utah's boundaries—to the site of present-day Las Vegas, in the New Mexico Territory. A third pushed 200 miles southeast, to what is now Moab, Utah.

In August, Young wrote to the Las Vegas missionaries, working among Paiutes, to congratulate them on the "prosperity and the success which has thus far attended your efforts" and to exhort them to start baptizing the Indians and to "[g]ain their confidence, love and esteem and make them feel by your acts that we are their real friends." In all, the missions would report baptizing scores of Indians. (What the Indians made of the ritual was not recorded.)

In an October 1, 1855, letter to a friend, John Steele, an interpreter at the Las Vegas mission, suggested another motive. "If the Lord blesses us as he has done," he wrote, "we can have one thousand brave warriors on hand in a short time to help to quell any eruption that might take place in the principalities." (In 1857, the Utah militia, under Young's command, would number about 4,000.)

The following summer, Young counseled secrecy to another church leader, John Taylor, president of the New York City-based Eastern States Mission (and, eventually, Young's successor as president of the church). "[M]issionaries to the Indians and their success is a subject avoided in our discourses and not published in the 'News,'" he wrote on June 30, 1856, to Taylor, who was also editing The Mormon, a newspaper widely read by Eastern Mormons. "Wherever any thing comes to hand no matter from what source it would be well to carefully look it over and draw your pen through all such as you might deem it wisdom not to publish."

But by 1857, non-Mormon newspapers from New York to California had begun reporting that the Mormons were seeking the Indians' allegiance in case of a clash with the United States. Some accounts were based on briefings from officials who had returned to Washington; others, based on gossip, tended toward a more alarmist tone. For example, on April 20, 1857, the National Intelligencer, a Washington newspaper, put the number of the Mormons' Indian allies at 300,000, even though the total Indian population of the Utah Territory appears to have been 20,000 at most. Young would characterize press coverage generally as "a prolonged howl of base slander."

Ultimately, none of the missions lasted. The southeast mission collapsed within four months after a skirmish with Utes; the Las Vegas mission followed, having shifted its focus from conversion to an abortive attempt at mining lead. The northern mission, called Fort Limhi, operated among the Bannock, Shoshone and others until March 1858.

By the time Young led his senior aides on an expedition there in April 1857, almost every federal official had left Utah. In Washington, a new president faced his first crisis.

James Buchanan, a Democrat, had defeated the Republicans' John Frémont and the Know-Nothings' Millard Fillmore in the 1856 election. He assumed the presidency in March 1857 preoccupied with the fight over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. But within weeks, reports from those who had fled Utah and strident petitions from the territorial legislature for greater influence over the appointment of federal officials turned his attention farther west.

Brigham Young's term as territorial governor had expired in 1854; he had served on an interim basis since. Buchanan, with his cabinet likening the Utah petitions to a declaration of war, decided to replace Young with Alfred Cumming, a former mayor of Augusta, Georgia, who was serving as an Indian-affairs superintendent based in St. Louis. He ordered troops to accompany the new governor west and to enforce federal rule in Utah—but, for reasons that are not clear, he did not notify Young that he was being replaced.

Young found out in July 1857, a month that brought a series of shocks to the Mormons. The Deseret News reported that Apostle Parley Pratt had been killed in Arkansas by the estranged husband of a woman Pratt had taken as his 12th wife. Rumors circulated that federal troops were advancing, prompting Apostle Heber C. Kimball to declare, "I will fight until there is not a drop of blood in my veins. Good God! I have wives enough to whip out the United States." Mormons traveling from the Kansas-Missouri frontier brought word that federal troops were, in fact, headed for Utah, leading to Young's announcement on the tenth anniversary of his arrival in the Great Salt Lake Valley.

It was in this heated atmosphere that, six weeks later, a California-bound wagon train that included 140 non-Mormon emigrants, most of them from Arkansas, made camp in a lush valley known as Mountain Meadows, about 40 miles beyond the Mormon settlement of Cedar City. Just before breakfast, according to an account by historian Will Bagley in Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, a child among the emigrants fell, struck by a bullet. As a party of men with painted faces attacked, the emigrants circled their wagons.

After a five-day siege, a white man bearing a white flag approached the emigrants. Mormons, he told them, had interceded with the attackers and would guarantee the emigrants safe passage out of Mountain Meadows if the Arkansans would turn over their guns. The emigrants accepted the offer.

The wounded and the women and children were led away first, followed by the men, each guarded by an armed Mormon. After half an hour, the guards' leader gave the order to halt. Every man in the Arkansas party was shot from point-blank range, according to eyewitness accounts cited by Bagley. The women and older children fell to bullets, knives and arrows. Only 17 individuals—all of them children under the age of 7—were spared.

For decades afterward, Mormon leaders blamed Paiute Indians for the massacre. Paiutes took part in the initial attack and, to a lesser degree, the massacre, but research by Bagley, Juanita Brooks and other historians has established that Mormons were culpable. Last September, on the 150th anniversary of the event, Mormon Apostle Henry B. Eyring, speaking for the church, formally acknowledged that Mormons in southern Utah had organized and carried out the massacre. "What was done here long ago by members of our Church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct," Eyring said. A "separate expression of regret," he continued, "is owed to the Paiute people who have unjustly borne for too long the principal blame for what occurred during the massacre."

In September 1857, Cumming and about 1,500 federal troops were about a month from reaching Fort Bridger, 100 miles northeast of Salt Lake City. Young, desperately needing time to prepare an evacuation of the city, mobilized the Utah militia to delay the Army. Over several weeks, militiamen raided the troops' supplies, burned the grass to deny forage to the soldiers' horses, cattle and mules, even burned Fort Bridger. November snowstorms intervened. Snowbound and lacking supplies, the troops' commander, Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, decided to spend the winter at what was left of the fort. The Mormons, he declared, have "placed themselves in rebellion against the Union, and entertain the insane design of establishing a form of government thoroughly despotic, and utterly repugnant to our institutions."

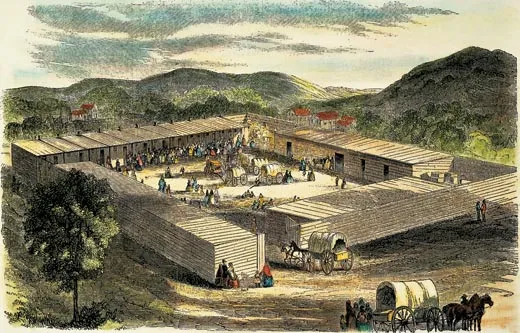

As the spring thaw began in 1858, Johnston prepared to receive reinforcements that would bring his force to almost 5,000—a third of the entire U.S. Army. At the same time, Young initiated what has become known as the Move South, an exodus of some 30,000 people from settlements in northern Utah. Before leaving Salt Lake City, Mormons buried the foundation of their temple, their most sacred building, and planted wheat to camouflage it from the invaders' eyes. A few men remained behind, ready to put houses and barns and orchards to the torch to keep them out of the soldiers' hands. The Mormons, it seemed, would be exterminated or once again driven from their land.

That they were neither is due largely to the intervention of their advocate Thomas Kane. Over the winter of 1857-58, Kane had set out for Utah to try to mediate what was being called "the Mormon crisis." Although his fellow Pennsylvanian President Buchanan did not provide official backing, neither did he discourage Kane's efforts. Kane arrived in Salt Lake City in February 1858. By April, in exchange for peace, he had secured Young's agreement to give way to the new governor. Many in the public, given Buchanan's failure to notify Young and the Army's delayed arrival in Utah, began to perceive the Utah expedition as an expensive blunder undertaken just as a financial panic had roiled the nation's economy. Buchanan, seeing a chance to end his embarrassment quickly, sent a peace commission west with the offer of a pardon for Utah citizens who would submit to federal laws. Young accepted the offer that June.

That same month, Johnston and his troops marched through the deserted streets of Salt Lake City—then kept marching 40 miles south to establish Camp Floyd, in present-day Fairfield, Utah. With the Army no longer a threat, the Mormons returned to their homes and began a long and fitful accommodation to secular rule under a series of non-Mormon governors. Federal laws against polygamy targeted Mormon property and power through the 1870s and '80s; Wilford Woodruff, the LDS Church's fourth president, issued a formal renunciation of plural marriage in 1890.

"The United States government used polygamy as a wrecking ball to destroy the old theocracy," says historian Bigler. "By 1890, Mormons were hanging on by their fingernails. But when Wilford Woodruff delivered his manifesto repudiating polygamy, he went further: he said that from now on, Mormons would obey the law of the land." Statehood for Utah followed in 1896.Their dreams of dominion over, the Mormons began to enter the American fold.

David Roberts is the author of the forthcoming Devil's Gate: Brigham Young and the Great Mormon Handcart Tragedy.