The American Plan to Build Nuclear Power Plants in the Ocean

This ill-advised scheme would have put gigantic barges just off the Atlantic coast? Where would it have started? New Jersey, of course

![]()

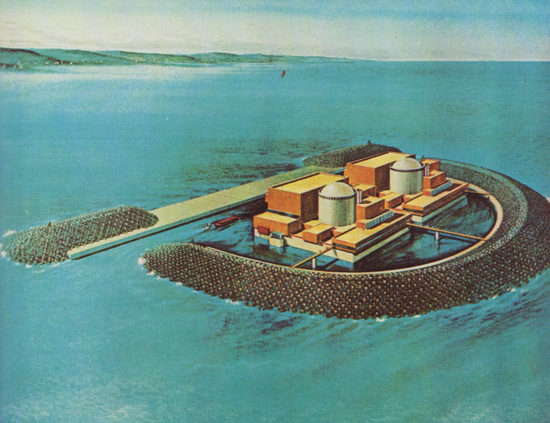

An artist’s 1972 drawing of an offshore nuclear power plant

A new nuclear power plant hasn’t been built in the U.S. in over 30 years. But in the 1970s nuclear power was still in many ways a low-emissions dream of the future.

In 1975, nuclear power accounted for about 4 percent of the electrical energy generated in the United States. But some people at that time were predicting that by the dawn of the 21st century, nuclear power might supply over 50 percent of electrical energy needed in this country. (Nuclear power currently produces 19.2 percent of electricity in the U.S.)

In the early 1970s, plans were set into motion which would have seen eight to ten offshore nuclear power plants built by 1999. Each power plant was envisioned to produce 1,150 megawatts of electricity, enough for a city of about 600,000 at the time.

The plan was devised by Offshore Power Systems (OPS), a partnership between Tenneco and Westinghouse. In 1972, a New Jersey utility company contracted with OPS to build an offshore nuclear power plant in Jacksonville, Florida, and tow it to New Jersey. The $1.1 billion contract to build the plant was even signed at sea — aboard a yacht just off the New Jersey coast. The power plants would have been gigantic barges anchored a few miles off the American coastline, starting with Brigantine, New Jersey.

Why build a power plant at sea? Nuclear power plants require a tremendous amount of water for cooling and moving nuclear power plants offshore provides easy access to water without raising the ire of potential protesters on land.

Gordon P. Selfridge’s 1975 paper “Floating Nuclear Power Plants: A Fleet on the Horizon?” notes the concern over access to water:

Since nuclear power plants have a tremendous impact on the surrounding community, problems and confrontations on land have contributed to the impending move offshore. Physically, the plants consume enormous amounts of water for cooling and steam production and emit low-level radiation. With reference to the “once-through” cooling water necessary for the plants’ operation, one study has projected that the demand for such coolant will encompass over fifty percent of the entire runoff from the continental United States in only twenty-five years unless the plants are moved offshore. The possible ecological impact of running half our river water through nuclear power plants has led many to conclude that such plants would be better built in the coastal zone.

News reports from the time indicated that officials expressed a desire to have less of an impact on the environment, which is a more pleasant way to say that it’s probably not good to have half of the nation’s water running through nuclear power plants. Officials were concerned that states friendly to nuclear power (like New Jersey) were running out of vital riverfront property on which to build plants — at least without angering environmental groups. From the September 19, 1972, News Journal in Mansfield, Ohio:

The stated reason for building the offshore power plant was to minimize its impact on the environment, but officials privately admitted that the move to the sea was motivated by the fact that New Jersey may be the first state in the United State to run out of riverfront property for power plants.

“This is the only reason for putting this plant in the ocean,” said Edward C. Raney, a Cornell University biologist and a public service consultant. “It’s the only way to justify the expense of locating at sea.”

But the project met with delay after delay, most stymied by growing public concern over the environmental impact and risk of accidents with nuclear power plants. In 1976, then-candidate for President Jimmy Carter called for a moratorium on new nuclear power plants in the United States. Public opinion was already turning against nuclear power in the mid-1970s but the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania on March 28, 1979, permanently altered the way that Americans perceived nuclear power.

In 1982, a federal nuclear licensing board gave temporary approval for the OPS program to go through in New Jersey. But by then OPS was barely hobbling along. In 1975, Tenneco had withdrawn from the project leaving just Westinghouse at the helm. And by the early 1980s all of the utility companies with which OPS signed contract had long since cancelled their orders on account of the delays.

Over the next decade OPS began liquidating everything and laying off most of their staff of 1,500 in Jacksonville. In 1990 Westinghouse sold what was then the world’s largest crane — 38 stories tall, and built for $15 million — to a Chinese shipbuilding company for a measly $3 million.

Today, environmentalists who once shunned nuclear power are giving it a second look. But with the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima on March 11, 2011, the world is again concerned about the very real potential for accidents — especially when it comes to shared resources like the ocean.

Selfridge wrote in 1975 (even before Three Mile Island) about the difference between an accident on land and one in the ocean: “A similar accident at sea, however, would have a far more devastating effect. A meltdown at sea would not create its own glazed insulation chamber. The poisonous reactor core would melt through the barge and descend into the hydrosphere where the radioactive core would contaminate thousands of cubic miles of ocean. Some radiation would be released to the atmosphere, the rest would enter the marine food chain. Radioactive contamination of the entire northwest Atlantic food chain for hundreds of years from one meltdown is a conceivable scenario.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)