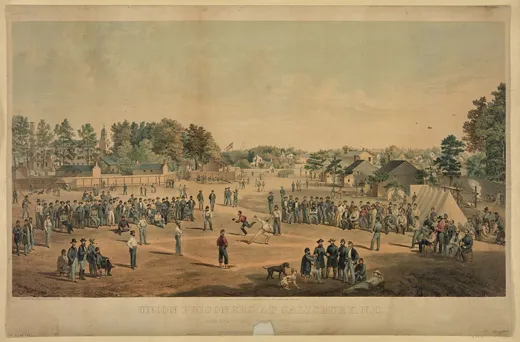

That Time More Than 150 Years Ago When Thousands of People Watched Baseball on Christmas Day

During the Civil War, two regiments faced off as spectators, possibly as many as 40,000, sat and watched

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Civil-Ware-Baseball-631.jpg)

On a Christmas morning in South Carolina 150 years ago, two teams took the field for a game of what was not yet the national pastime.

The epic Christmas Day faceoff between two teams representing New York regiments stationed on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, may be one of the most significant contests in baseball’s early decades, even though it retains a whiff of mystery.

Details are scarce. We don’t even know the final score. But it was played before an enormous audience: various sources say 40,000 people watched the game on Hilton Head—also known then as Port Royal—on that Christmas morning.

We do know one of the players: A.G. Mills. Then a young private with the 165th New York Regiment, Mills later went on to become president of the National League. It was probably his re-telling of the great Christmas Day game that helped add to its mystique—although, for reasons we shall explain, Mills is hardly the most reliable source on baseball history, least of all his own.

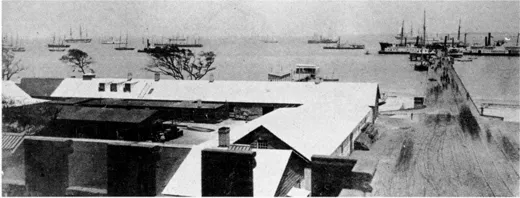

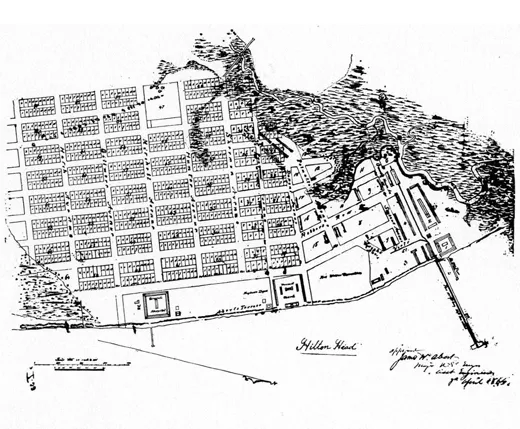

Why Hilton Head? In 1862, it was not yet a tourist destination or golf mecca but rather, the site of an enormous federal base. The 12-mile-long, 5-mile-wide island was a linchpin in the Union’s three-pronged “Anaconda” plan, formulated at the outbreak of hostilities to squeeze the Confederacy into submission. “Hilton Head was at the center of one of those three prongs…the blockade,” says Robert Smith, past president of the Heritage Library Foundation, a Hilton Head historical organization. (The other two prongs were attacking up the Mississippi River from New Orleans and an invasion of Virginia.) The island’s strategic location between Savannah and Charleston made it an ideal refueling and supply base for ships involved in the Union naval blockade, denying the Confederacy supplies or access to the cotton markets of Europe.

In November, 1861, Federal troops had seized the island, then home to 25 plantations, and never relinquished it throughout the war. About 13,500 troops came ashore in the invasion, bringing with them 1,500 horses and another 1,000 civilian construction workers who set out to create one of the most formidable military installations of the war.

“People poured in, and they built this city,” said Smith. A town center was constructed, with a department store, a U.S. post office, a three-story hotel and a theater. To help re-coal the ships enforcing the blockade, a 1,600-foot-long dock was built, as was a massive military hospital. There were also schools on the island, set up by the American Missionary Society to educate the children from among the population of 9,000 freed slaves. And of course, there were vast tent cities where thousands of Union troops were bivouacked. There, surrounded by water, the men drilled and labored.

Except on Christmas Day.

On that rare day off, soldiers looked for ways to relax. One way in 1862 was playing and watching baseball, New York style.

While most soldiers from the North would have been familiar with some form of bat and ball game, the version played in New York and Brooklyn was the one that had exploded in the late 1850s. New York games differed from others—-most notably the style practiced in Massachusetts—in that they were played on a diamond shape field, nine men on a side, with rules prohibiting “soaking” (throwing the ball at a runner to record an out, which was legal in other early forms of the game).

Pitchers in this era threw underhand; but there were fair and foul balls. The positions were the same, although sometimes the second baseman played closer to that base, and the shortstop played in the outfield.

“It would have probably resembled a Sunday morning old guy’s softball game,” says George B. Kirsch, professor of history at Manhattan College and author of Baseball in Blue & Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War. “The idea was to get the ball into play, so scores were usually pretty high.”

In his book, Kirsch describes the Massachusetts game--the other major style of baseball at the time --as being descended from a bat and ball game that was played in New England as far back as the 1700s. The Massachusetts style of baseball he presents as "similar to New England townball, with a square field, overhand pitching, no foul territory, ten to twelve men per side, one out to retire all and victory belonging to the team that first scored one hundred runs."

Given the popular preference for the New York brand of baseball, it was no accident that the game held on Christmas Day was between teams representing New York regiments, Mills’ 165th, and a “nine” composed of members of the 47th and 48th New York.

The game’s attendance has sparked debate over the years. Some say that it couldn’t have possibly been the 40,000 or even 50,000 mentioned by Mills and others. Baseball writer Alex Remington, writing about the Christmas Day game on Fangraphs, in December, 2011, is suspicious because of what he calls “the unreliable source at the heart of the story.” That would be Mills who, in the early 1900s, was appointed head of a committee that sought to investigate the origins of baseball, and came up with the now widely discredited fable of the game having been invented in Cooperstown, New York, by Abner Doubleday (himself a Union Army general during the war.)

While Mills may or may not have embellished the size of the Christmas Day game, Smith thinks that higher attendance numbers are entirely plausible, pointing out that in addition to the troops on the island, there were thousands of freed slaves, civilian workers, teachers and their families, and Confederate prisoners of war. Moreover, the extensive dunes on Hilton Head at the time would have provided excellent, elevated seating for spectators. The natural undulations of the dunes would have also allowed for more easy segregation, enabling African Americans to watch, as well as whites (while slavery had been abolished in April 1862 the Sea Islands, of which Hilton Head is one of, there was still little socializing between the races).

"The controversy about the number of people that could have attended is interesting,” says Smith. “So few think about the number of freed slaves there were on the Island at the time. The officers could have brought their wives. Or the prisoners on the island. All of these people could have very well attended.”

Whether it was 10 or 20 or 40,000 in attendance, it is likely that many in the crowd were exposed to the New York game of baseball for the first time that day—or at least, got to see it played proficiently. If, as Kirsch says, the Civil War is often seen as having advanced baseball’s popularity throughout America, then the most widely attended game of the war must have had some impact.

Still as Smith says, “it was a one day event to amuse the troops.” Nor was baseball the only entertainment—and maybe not even the most popular. According to a 2010 article in the local Hilton Head paper about the game, the Union-run newspaper on the Island mentioned the game (no crowd figure), but noted that it was played "after a demonstration of fire engines and a huge meal." The game was likely the culminating event in a day's program of activities.

While the Union encampment had no designated ball field (most likely the teams played on an open space or one of the parade grounds), they did have the Union Theater where, for the price of a 50 cent ticket, audiences could enjoy a performance of such dramatic fare as “Temptation of the Irish Immigrant.” Consider that in the regimental history of the 48th New York Volunteers, published in 1885, a mere paragraph is allotted to their baseball “nine”—and no mention at all is made of the Christmas Day game.

By contrast, three pages are devoted to the regiment’s theatricals, which are described as “the great source of amusement” for the men. Speaking of the theaters in which the their troupe performed in, including the one on Hilton Head, the regimental historian declared that “it’s doubtful if anything was as fine in the war.”

While the Civil War in general, and the Christmas Day game in particular, may have been important in the growth of the game in the decades to follow, it would seem that for soldiers in 1862, hamming it up on stage was the real national pastime.