The Story of the First Mass Shooting in U.S. History

Howard Unruh’s “Walk of Death” foretold an era in which such tragedies would become all too common

:focal(1589x726:1590x727)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/4d/664d83dd-ebe2-45b9-abb8-e1bebfaf5a38/u1122672inp.jpg)

On Labor Day, 1949, Howard Unruh decided to go to the movies. He left his Camden, New Jersey, apartment and headed to the Family Theatre in downtown Philadelphia. On the bill that night was a double feature, the double-crossing gangster movie I Cheated the Law and The Lady Gambles, in which Barbara Stanwyck plays a poker-and-dice-game addict. Unruh, however, wasn’t interested in the pictures. He was supposed to meet a man with whom he’d been having a weeks-long affair.

Unfortunately for Unruh, 28 years old at the time, traffic held him up and by the time he reached theater, a well-known gay pick up spot on Market St., his date was gone. Unruh sat in the dark until 2:20 a.m., bitterly stewing through multiple on-screen loops of the movies. At 3 a.m., he arrived home in New Jersey to find that the newly constructed fence at the rear end of his backyard—one he’d erected to quell an ongoing feud with the Cohens who lived next door and owned the drugstore below the apartment he shared with his mother—had been tampered with. The gate was missing.

It was the final straw. For a couple of years, Unruh had been contemplating killing several of his Cramer Hill neighbors over petty squabbles, perceived slights and name-calling, all which fed into his psychosis. Unruh thought the world was out to get him, so he decided to enact revenge on his little corner of it. He went into his apartment, uncased his German Luger P08, a 9mm pistol he’d purchased at a sporting goods store in Philadelphia for $37.50, and secured it with two clips and 33 loose cartridges. Unable to sleep, he made yet another mental list of his intended targets, a group of local shopkeepers one would find in a 1950s children’s book: the druggist, shoemaker, tailor and restaurant owner. Eventually, Unruh dozed off.

In a few hours, on the morning of Tuesday, September 6, Unruh would embark upon his “Walk of Death,” murdering 13 people and wounding three others in a 20-minute rampage before being hauled off by police after a dangerous firefight. A somewhat forgotten man outside of criminology circles and local old-timers, Unruh was an early chapter in the tragically-all-too-familiar American story of an angry man with a gun, inflicting carnage.

**********

There have been killers since Cain murdered Abel, and Unruh certainly wasn’t the first American to take the lives of multiple victims. The FBI defines a “mass murder” as four or more victims in a single incident (usually in one spot). Serial killers and spree killers fall into their own category, and there’s also a new crowdsourced "mass shooting" tracking system that counts the number of people shot, as opposed to killed, but it’s not an official set of data. What is known is that the United States, with five percent of the world’s population, was home to nearly one-third of the world’s mass shooters from 1966-2012. Before that, mass gun murders like Unruh’s were too rare to be considered a threat.

“There have been notorious killers since America was founded, but you didn’t have the mass shooting phenomenon before Unruh’s time because people didn’t have access to semi-automatic weaponry,” says Harold Schechter, a true crime novelist who has written about infamous murderers going back to the 19th-century.

While the terminology is a bit fungible, Unruh is generally regarded as the first of the “lone wolf” type of modern mass murderers, the template for the school and workplace shooters who have dominated the coverage of the more than 1,000 victims since 2013. Unruh was a distinctive personality type, one that has also come to define those who have followed in his bloody footsteps.

“Unruh really matches the mass murder profile. He had a rigid temperament, an inability to accept frustration or people not treating him as well as he wanted, and a feeling of isolation, all things people accept and move on from,” says Katherine Ramsland, a professor of forensic psychology and the director of the master of arts in criminal justice at DeSales University, as well as the author of some 60 nonfiction books including Inside the Mind of Mass Murderers: Why They Kill. “He had a free-floating anger, held grudges, owned weapons he knew how to use, and decided somebody was going to pay. It’s a typical recipe for internal combustion.”

Unruh learned how to use weaponry in World War II, serving in the 342nd Armored Field Artillery and taking part in the relief of Bastogne in the Battle of the Bulge. He occasionally served as a tank gunner and received commendations, although he never rose above the rank of private first class. His commanders said he followed orders well. However, while in combat, he kept meticulous notes of every German he killed. He would mark down the day, hour, and place, and when circumstances allowed, describe the corpses in disturbing bloody detail. After the killings, Unruh’s younger brother, Jim, would tell reporters that he wasn’t the same after the service and that he “never acted like his old self,” but Howard was honorably discharged with no record of mental illness.

Back in Camden, Unruh decorated his apartment with war collectibles. His peeling walls were adorned with pistols and bayonets, while machetes and ashtrays crafted out of German shells laid about the room. In the basement, he set up a target range and practiced shooting, even though a low ceiling meant he could only fire from a kneeling or lying position. One gun he shot was a prized Nazi Luger he brought back as a souvenir.

Prior to joining the army in 1942, Unruh had lived a normal, if unremarkable, life. He was born on January 20, 1921 to Sam and Freda (sometimes referred to as Rita) Unruh. They separated when Howard was a boy. He and Jim were raised in Camden by their mother, who worked as a packer at the Evanston Soap Company. The October 1949 psychiatric report that formally declared Unruh insane, noted that Unruh had a “rather prolonged period of toilet training” and “did not walk or talk until 16 months old,” but otherwise he was basically an average unassuming kid. He was pious, regularly read the Bible and attended services at St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Howard was shy, kept to himself for the most part, consumed with his two favorite hobbies, stamp collecting and building model trains. He wasn’t a drinker or a smoker, even as an adult. The yearbook from Woodrow Wilson High noted his ambition was to work for the government and fellow students called him “How.”

Between high school and World War II, Unruh worked a series of blue-collar jobs, which he picked up for a spell after returning from Europe. He worked for a printing outfit, the Acorn Company, and then operated a metal stamping press at Budd Manufacturing, but neither job lasted a year. His one stab at a career came when he enrolled in pharmacy school at Temple University, but he dropped out after a few months. By December of 1948, he was unemployed and living full-time with his mother back in Cramer Hill. He ventured out in his neighborhood, but didn’t have any friends he called upon. A psychiatrist would later write, “After WWII, after [Unruh] returned home, he did not work nor did he any life goals or directions, had difficulty adjusting or solving problems and was, ‘angry at the world.’”

Unruh’s rage festered. In his mind, everyday ordinary happenings became acts of aggression that demanded retribution. And so, he began to keep thorough lists of his grievances and slights, both real and imagined. In the 1949 commitment report, Unruh claimed Mr. Cohen short-changed him five times while Mrs. Cohen told him to turn down his music—the dulcet sounds of Brahms and Wagner—even though their son Charles was free to aggravate him with his trumpet. Other neighbors on Unruh’s list included: The man and woman who lived below him and threw trash on his back lot, the barber who put dirt in a vacant yard that backed up the drainage and flooded his cellar, the shoemaker who buried trash close to his property, and a mystery boy named “Sorg,” who tapped his electricity to light up the Christmas trees he was selling on the street.

Unruh’s paranoia about what was being said of him around Cramer Hill fueled his persecution complex, he was certain everyone was insulting him. He felt that a number of people knew he was a homosexual and were talking about it, said Mr. Cohen called him a “queer,” said the tailor (and son) was spreading a story that “he saw me go down on somebody in an alley one time,” and was fearful local teenagers who frequently harassed him had seen him at the Family Theatre.

Unruh was a gay man; he was up front with the psychiatrists who interviewed him following the massacre. From 1944-46, he’d had a girlfriend, seemingly the only one of his life, but broke it off after telling her he was “schizo” and would never marry her. He told the psychiatrists that she meant nothing to him and that they’d never had sex. Following their break-up, he’d been with a lot of men and said he’d once contracted gonorrhea. After dropping out of Temple in 1948, he kept his room in a Philadelphia lodging house for nearly a year saying that “his interest in religion declined when his sexual relations with male friends increased.” Ann Mitchell, an African-American maid who cleaned the rooms, told detectives investigating the massacre that she’d seen him going to and from his room with other men at all times of the day and added he would write “nigger” in the dust on the writing desk after returning from weekends in Camden. The report noted, “As {Mitchell} disliked him, she paid little attention to him and she never suspected him of anything.” Unruh paid his $30 a month on time from September 28, 1948, until August 28, 1949, and then never returned.

The sad irony is that the one aspect of Unruh that people did “suspect,” being a homosexual, was accurate, but he couldn’t live as an open gay man in an era when it wasn’t just societally unacceptable, it was illegal. What most Cramer Hill people didn’t suspect, even while finding him rather strange, was that he was a powder keg. In Seymour Shubin’s article, “Camden’s One-Man Massacre,” which took up the entirety of the December 1949 issue of Tragedy-of-the-Month, tailor Tom Zegrino described a pre-shooting Unruh as “awfully polite. The kind of guy who wouldn’t hurt a flea.” His wife of less than a month Helga, who would be one of Unruh’s last victims added, “I think he’s a nice fellow. He seems devoted to his mother, too. That’s something I like.”

**********

Sometime around 8 a.m. on September 6, just hours after returning from Philadelphia, Unruh was awakened by his mother, who prepared him a breakfast of fried eggs and milk. After eating, Unruh went into the basement and retrieved a wrench, which he raised over her in a threatening manner. “What do you want to do that for, Howard?,” she asked him. Freda would later say her son appeared to be transfixed. She repeated her question over and over before running out of the house to a neighbor, fearing her son had reached the tipping point. (A short while later, after hearing gunfire and putting it all together, Freda fainted.)

Unruh immediately collected his Luger and ammo, a six-inch knife, and a tear gas pen with six shells, and cut through the backyard to the 3200 block of River Road. Dressed in a brown tropical-worsted suit, white shirt, striped bow tie, and Army boots, the lanky 6-foot, 164-pound Unruh shot at a bread deliveryman in his truck, but missed. He then walked into the shoemaker’s store and, without saying a word, shot John Pilarchik, the 27-year-old cobbler who was on his list, in the chest. Pilarchik fell to the floor. Still alive, Unruh fired another round into Pilarchik’s head. A young boy crouched in fear behind the counter.

Unruh walked back out to the street and entered the barbershop next door. Clark Hoover, 33, was cutting the hair of Orris Smith, 6, who sat atop a white carousel-style horse as his mother, Catherine, looked on. The barber tried to protect the child, but Unruh killed the boy with a bullet to the head. A second shot ended Hoover’s life. Unruh ignored Catherine, 42, who carried Orris into the street screaming until a neighbor threw them both in the car and sped away to the hospital. The next day, the horrific scene was described by Camden Courier-Post columnist Charley Humes:

“…People were peering through a big plate glass window, looking at a ‘hobby horse’ in a barber shop that is closed.”

At the base of the standard which held the wooden horse in place was another blotch of blood…the blood of another little boy ‘just past six’ who was having his hair cut in preparation for his first trip to school the next day…”

Back on River Road, Unruh shot at a boy in a window, but missed. He then fired into a tavern across the street owned by Frank Engel. In a 1974 Courier-Post retrospective, Engel said Unruh had never come inside the bar, but that he’d seen him “walk down the street, walking straight like he had a poker in his back and the kids on the corner would make some remarks about him.” Nobody was hit as Engel ran upstairs and grabbed his .38 caliber Luger. Meanwhile, Unruh reloaded and headed into the drugstore to confront his primary targets, the Cohens.

An insurance man, James Hutton, 45, was coming out of the drugstore to see what the commotion was all about. He came face-to-face with Unruh, but didn’t move quickly enough when the killer said excuse me. Realizing his time free of police was growing short, Unruh shot Hutton, saying, “I fired on him once, then stepped over him and went into the store.” He saw Maurice, 40, and his wife Rose, 38, running up the stairs into their apartment. Rose hid in a closet (and put son Charles, 12, in a separate one), but Unruh shot three times through the door before opening it and firing once more into her face. Walking across the apartment, he spotted Maurice’s mother Minnie, 63, trying to call the cops, and shot her multiple times. He followed Maurice onto a porch roof and shot him in the back, sending him to the pavement below.

Maurice Cohen was dead on the sidewalk, but Unruh continued his rampage. Back out on River Road, he killed four motorists who found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. He leaned into a car driven by Alvin Day, 24, a television repairman and World War II vet who slowed down at the corner where Hutton’s body lay, and fired. Following Day’s murder, accounts vary, but most likely Unruh next walked out into the street to a car stopped at a red light and fired into the windshield. He instantly killed the driver Helen Wilson, 37, and her mother Emma Matlack, 68, and wounded Helen’s son, John Wilson, 9, with a bullet through the neck. He returned to the same side of the street with the goal of claiming his final two victims.

Unruh entered the tailor shop, looking for Tom Zegrino, but only found Helga, 28. She was on her knees begging for her life when Unruh shot her at close range. Next door, Thomas Hamilton, less than two weeks shy of his third birthday, was playing with the curtain near his playpen and looked out the window. Unruh said he mistook the moving shadows for one of the people he believed was dumping trash in his yard and shot through the window, striking Hamilton with a bullet to the head.

On his final stop after darting back into the alleyway, Unruh broke into a home behind his apartment lot and wounded a mother and son, Madeline Harrie, 36, and Armand, 16, before running out of ammo and retreating to his apartment. By now, sirens were wailing.

In 20 minutes, Howard Unruh had killed 12 and severely wounded four. (The toll would rise to thirteen; John Wilson, the 9-year-old car passenger, later died at the hospital.) His Cramer Hill neighborhood was rattled, to the point where a detective on the scene would say, years later, that the mailman dropped his full bag on the sidewalk, quit his job, and never came back.

Unruh returned to his apartment as a crowd of authorities and neighborhood civilians gathered. In 1949, mass shootings were basically unheard of, so there was no official police protocol. As neighbors milled about, more than 50 officers surrounded the two-story stucco building, and began blasting away at the apartment with machine guns, shotguns, and pistols, even though some in the crowd, estimated to be a thousand people, were in the line of fire.

(How haphazard was police work back then? The magazine Weird N.J. discovered what became of Unruh’s Luger. Detective Ron Conley, following typical 1940s procedure, secured it in his locker. Upon retiring, he brought it home. It was recovered in the early 90s, returned to the Camden County Prosecutor’s Office, and marked as evidence.)

During the onslaught, Philip W. Buxton, an enterprising assistant city editor at The Camden Evening Courier, looked up Unruh’s number in the phone book, rang it up, and to his surprise, had the shooter on the line. Buxton chatted with Unruh for a few minutes as the bullets poured into the apartment, shattering window panes. He asked how many people he’d killed, to which Unruh replied, “I don't know yet, I haven't counted them. But it looks like a pretty good score.” Buxton followed-up asking why he was killing people. Unruh said he didn’t know, but he had to go because “a couple of friends are coming to get me.”

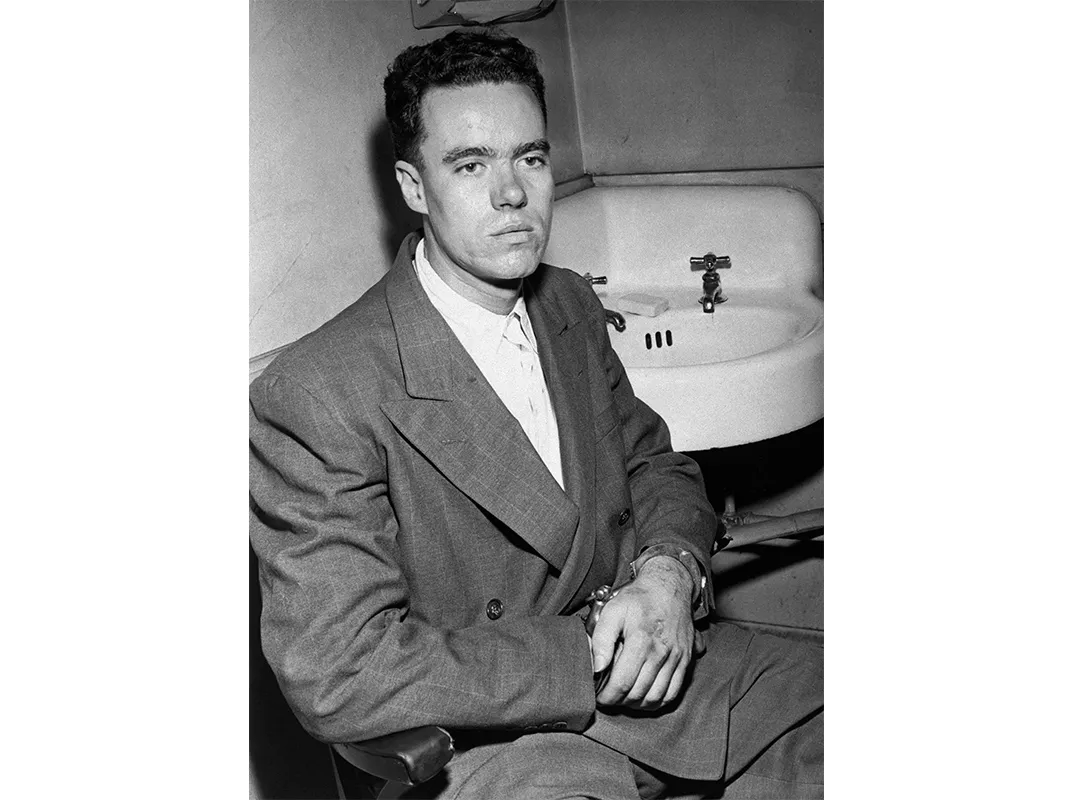

In the chaos, a couple of policemen climbed onto the roof—the same one Maurice Cohen plunged from—and lobbed a tear gas canister into Unruh’s apartment. The first was a dud, but the second was stingingly effective. Five minutes later Unruh called out that he was surrendering. He shouted he was leaving his gun on a desk and walked out the back door with his hands held high. He was patted down and cuffed as gawkers screamed for the mass murderer to be lynched right then and there. One furious cop demand to know, “What’s the matter with you? You a psycho?”

Unruh flatly replied, “I am no psycho. I have a good mind.”

**********

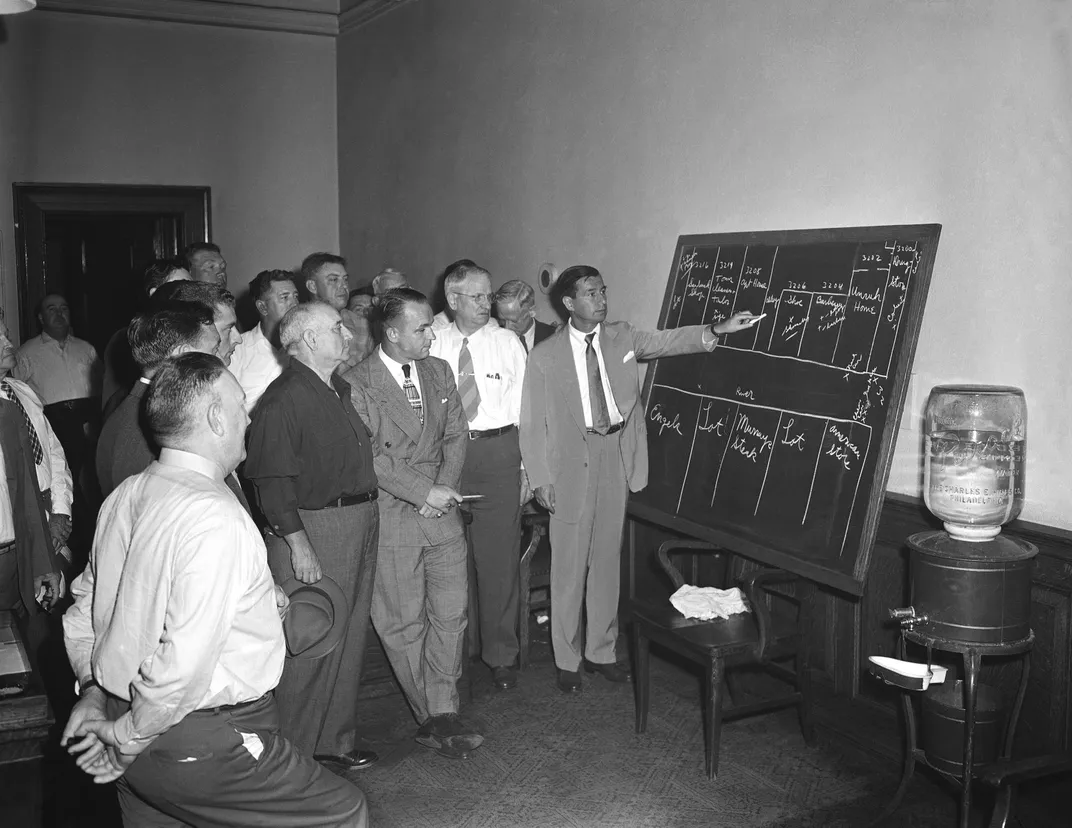

For the next couple of hours, Unruh would be grilled in a Camden detective’s office.

He took full responsibility for the killings and supplied details in a detached clinical manner. During the interrogation, District Attorney Mitchell Cohen (no relation to the druggist) noticed a pool of blood under Unruh’s chair. At one point late in the rampage, Unruh was shot in the buttock or upper leg by Frank Engel, who had taken aim from his upstairs window. Unruh was rushed to Cooper Hospital, the same one as his victims, but surgeons were unable to remove the bullet. Less than 24 hours after his arrest, he was transferred to the Vroom Building for the criminally insane at Trenton Psychiatric Hospital, voluntarily. He would remain on the grounds for the next 60 years as Case No. 47,077. Unruh would never stand trial for the “Walk of Death.”

Starting on September 7, a team of psychiatrists examined Unruh for weeks, trying to get an understanding of why he did what he did. Many of their findings weren’t released until 2012, at the request of the Philadelphia Inquirer. He cold-bloodedly explained everything, listing the neighbors who had wronged him, and describing each murder with little emotion. He claimed to feel sorrow for the children he’d killed, but the doctor’s notes indicate he didn’t seem remorseful. Unruh went so far as to say that “murder is sin, and I should get the chair.”

The full accuracy of Unruh’s statements is unknowable because on more than occasion, psychiatrists administered truth serum, a.k.a. narcosynthesis, which was then considered useful. Scientists discredited it in the 1950s because patients often melded fact and fantasy together. (In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled truth serum confessions unconstitutional in Townsend v. Sain.) It’s impossible to know the veracity of the reports from Unruh’s sessions, such as the one where he told a doctor that he’d been in bed with Freda, fondled his mother’s breasts, and that “their privates touched.” However, a psychiatrist notes in a “Personal History” summation that Unruh’s brother James said “once the patient had made advances to him when they were sleeping together, which he, James, had vigorously resisted.”

On Oct. 20, 1949, a Camden County judge signed a final order of commitment based on a diagnosis of “dementia praecox, mixed type, with pronounced catatonic and paranoid coloring.” In standard parlance, he was declared a paranoid schizophrenic. Unruh was considered too mentally ill to stand trial, although the murder indictment remained if ever he were “cured.” (So the missing Luger could have been vital evidence in a trial.) Ramsland believes Unruh’s initial diagnosis was wrong, and that today, he would have been found legally sane.

“He wouldn’t have been diagnosed with schizophrenia because he didn’t have any actual symptoms of schizophrenia, they just didn’t know what else to do in those days,” she says. “Back then, paranoid schizophrenia was kind of a trash-can diagnosis. You could put anything in there, but the criteria have tightened up since. Unruh didn’t have command hallucinations or anything like that. The standard is, are you so floridly psychotic that you don’t know what you’re doing is wrong? You can be psychotic and still get convicted. I suspect Unruh had a personality disorder, but it’s clear he knew what he was doing was wrong and that there were legal consequences. I always found it so odd that they just locked him away and forgot about him. Thirteen people were killed, are you kidding?”

Unruh’s father Sam was ordered to pay $15 a month for Howard’s upkeep in Trenton. And basically, for the next six decades, Unruh vanished. Occasionally, something would come up like in 1964, Unruh wrote a petition to have his indictment dismissed on the grounds he was insane at the time of the shootings. He withdrew it, probably upon understanding that it would only be useful as a defense in a trial, which he did not want. Freda visited him until her death in 1985, but after that, Unruh didn’t talk much. Over the years, he did take an art class, and in the 1970s had an unrequited crush on a much younger inmate, but for the most part, he kept up with his stamp collection and was known to mop the floors while muttering to himself.

In 1991, a psychiatrist said Unruh had one friendship inside, but actually it was “a person who just keeps talking all the time. Mr Unruh is a good listener.” In 1993, Unruh was transferred to a less restrictive geriatric unit, where he would live out his days. He died on October 19, 2009 at the age of 88.

**********

Technically, Unruh wasn’t the first mass shooter. There had been at least two, including one less that a year before in nearby Chester, Pennsylvania. Melvin Collins, 30, opened fire from a boardinghouse, killing eight before taking his own life, but his story was quickly forgotten. He doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page. Part of the reason Unruh is known as the “father of mass murderer” is that he didn’t follow the typical script. He, somewhat miraculously considering the firepower aimed his way, lived.

“Mass murder is typically a suicidal act in which apocalyptic violence is used to enact extreme vengeance, and it almost always ends in the perpetrator’s death,” says Schechter. “Unruh was the rare exception and he became the public face of a serious horrifying crime.”

Unruh didn’t lack for publicity. It was covered extensively by local newspapers and his homicidal terror was brilliantly re-created by famed New York Times writer Meyer Berger who left Manhattan at 11 a.m., interviewed at least 20 people in Camden by himself, and filed 4,000 words an hour before deadline. For his masterwork, Berger won the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting. (He sent the $1,000 prize money to Freda Unruh.) The piece remains a staple of journalism scholarship today.

Unruh’s “Walk of Death” is certainly infamous and well known in criminology circles, so it’s a bit curious that he’s fallen off the radar as a public figure. There were periodic articles published about Unruh throughout his long life, especially when Charles Cohen, the boy who hid in the closet, came out publicly after 32 years to denounce the prisoner’s request to be moved to a less-restrictive setting. In 1999, Cohen, 62, told the Philadelphia Inquirer that he was haunted by the morning, that other mass killings like Columbine brought back the pain, and that he was waiting for the call that Unruh had died. “I’ll make my final statement, spit on his grave, and go on with my life,” he said. Cohen passed away one month before Unruh.

Unruh’s massacre was a watershed crime, but it’s been usurped by other deadlier shooters of the television and internet age. A Google news search of “Howard Unruh” and “Umpqua” turned up no results, while an October 4 New York Times article about profiling mass killers said, “The episode…that some academics view as having ‘introduced the nation to the idea of mass murder in a public space’ happened in 1966, when Charles Whitman climbed a tower at the University of Texas at Austin and killed 16 people.”

Schechter says another reason Unruh isn’t as renowned is because the “Walk of Death” was seen as a stand-alone atrocity of a “crazy.” Mass murder wasn’t a regular occurrence and Unruh didn’t spark copycats—Whitman was years later—so it didn’t tap into common fears of the post-World War II generation. “Unruh’s killings were seen as a weird aberration and not something the culture was obsessed by, so he didn’t immediately enter into a larger American mythology,” says Schechter.

**********

One place where Unruh hasn’t been forgotten is the Cramer Hill neighborhood where he destroyed so many lives. River Road is still working-class, dotted with Mexican shops these days, but the layout is generally the same. The barbershop was torn down, but the buildings that housed the tailor, cobbler, and drugstore are all intact. The block looks the same. There are no plaques, memorials, or markers of any kind.

In late September, a 76-year-old Vietnam War veteran working as a school crossing guard on River Road, told me that when he moved to East Camden in 1977, many people who lived through that awful day were still around. He said even now, neighbors knows the legend of the “Walk of Death.” He pointed to Unruh’s apartment, which has reportedly remained empty since he was arrested. The outer wall of the apartment building was re-stuccoed and painted gray at some point, but plenty of indentations remain, presumably from the hailstorm of bullets. The crossing guard took me into Unruh’s backyard, the rear entrances boarded shut with cheap padlocks. By all appearances, the residential part of the building was shuttered and abandoned after Unruh killed 13 people in Cramer Hill. The back lot was overgrown with weeds and tall grass, but someone beautified it a bit by planting tomatoes and corn. The ears were growing on the other side of a chain-link fence.

The gate, however, was missing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_2851_thumbnail_copy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_2851_thumbnail_copy.png)