Salk, Sabin and the Race Against Polio

As polio ravaged patients worldwide, two gifted American researchers developed distinct vaccines against it. Then the question was: Which one to use?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/polio-patients_header.jpg)

They were two young Jewish men who grew up just a few years apart in the New York area during the Great Depression, and though they were both drawn to the study of medicine and did not know each other at the time, their names would, years later, be linked in a heroic struggle that played out on the front pages of newspapers around the world. In the end, both Albert Sabin and Jonas Salk could rightfully claim credit for one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments—the near-eradication of polio in the 20th century. And yet debate still echoes over whose method is best suited for the mass vaccination needed to finish the job: Salk’s injected, dead-virus vaccine or Sabin’s oral, live-virus version.

Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In the first half of the 20th century, Americans lived in fear of the incurable paralytic poliomyelitis (polio) disease, which they barely understood and knew not how to contain. That the disease led to some kind of infection in the central nervous system that crippled so many children, and even a president (Franklin D. Roosevelt) was alarming enough. But the psychological trauma that followed a neighborhood outbreak resonated. Under the mistaken belief that poor sanitary conditions during the “polio season” of summer increased exposure to the virus, people resorted to measures that had been used to combat the spread of influenza or the plague. Areas were quarantined, schools and movie theaters were closed, windows were sealed shut in the heat of summer, public swimming pools were abandoned, and draft inductions were suspended.

Worse, many hospitals refused to admit patients who were believed to have contracted polio, and the afflicted were forced to rely on home care by doctors and nurses who could do little more than fit children for braces and crutches. In its early stages, polio paralyzed some patients’ chest muscles; if they were fortunate, they would be placed in an “iron lung,” a tank respirator with vacuum pumps pressurized to pull air in and out of the lungs. The iron lungs saved lives, but became an intimidating visual reminder of polio’s often devastating effects.

Parents carry a stricken child during the polio scare. Photo: Wikipedia

By the early 1950s, 25,000 to 50,000 people were becoming infected each year, and 3,000 died from polio in 1952. Parents and children lived in fear that they would be next. The public had been clamoring for some kind of relief as the media reported word of possible vaccines in development. Government as well as corporate and private money flowed into research institutes, led by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (which later became the March of Dimes, for its annual fund-raising campaigns).

At the same time, the two New Yorkers, Salk and Sabin, now living in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, respectively, raced against the clock, and each other, to cure the dreaded disease.

Jonas Edward Salk was born in 1914, the son of Ashkenazi Jewish Russian parents who had immigrated to East Harlem. A gifted student, Salk enrolled at the New York University School of Medicine, but showed little interest in practicing. He was inspired by the intellectual challenges of medical research, particularly his study of the influenza epidemic that claimed the lives of millions after World War I. With his mentor, Thomas Francis Jr., he worked to develop an influenza vaccine.

Salk had an opportunity to pursue a PhD in biochemistry, but he did not want to leave medicine. “I believe that this is all linked to my original ambition, or desire,” he later said, “which was to be of some help to humankind, so to speak, in a larger sense than just a one-to-one basis.”

During World War II, Salk began postgraduate work in virology, and in 1947 he began studying infantile paralysis at the University of Pittsburgh Medical School. It was there that he devoted his research to developing a vaccine against polio, concentrating not on the live vaccines that other researchers had been experimenting with (at great peril; one test killed six children and crippled three more), but with a “killed virus” that Salk believed would be safer.

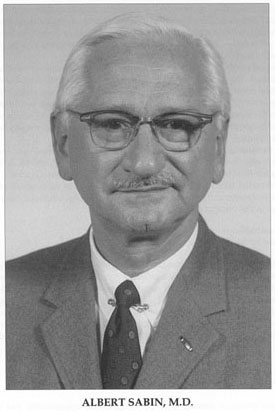

Dr. Albert Sabin. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Albert Bruce Sabin was born to Jewish parents in Poland in 1906 and came to the United States in 1921 when his family, fleeing religious persecution, settled in Paterson, New Jersey. Like Salk, Sabin attended medical school at New York University, and after graduating in 1931, he began research on the causes of polio. After a research stint at the Rockefeller Institute, Sabin left New York for the Children’s Hospital Research Foundation in Cincinnati, where he discovered that the polio virus lived and multiplied in the small intestine. An oral vaccine, he believed, might block the virus from entering the bloodstream, destroying it before it spread.

Salk cultivated polio viruses on cultures of monkey kidney cells, killed the viruses with formaldehyde, then injected the killed virus into monkeys. The experiments worked. The next step was to test the vaccine on humans, but many wondered who would volunteer to be injected with the polio virus, killed or not. Salk provided the answer: He injected himself and his wife and children—the first humans to be inoculated. In 1954, a large-scale field trial was arranged, with the support of major pharmaceutical companies, and nearly two million schoolchildren between the ages of 6 and 9 participated in the study. One half received the vaccine, the other half a placebo. Then everyone waited.

In Cincinnati, Sabin and his research associates swallowed live avirulent viruses and continued to perform trials on prisoners at a federal prison in Chillicothe, Ohio, where volunteer inmates were paid $25 and promised “some days off” their sentences. All thirty prisoners developed antibodies to the virus strains with none taking ill, and the trials were deemed successful. Sabin wanted to do even larger studies, but the United States would not permit it, so he tested his vaccine in Russia, East Germany and some smaller Soviet Bloc countries.

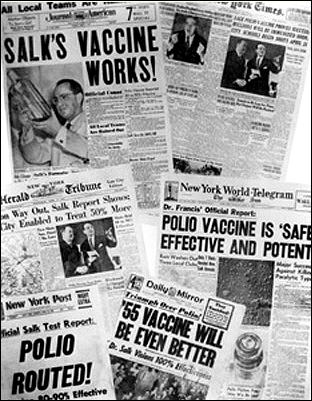

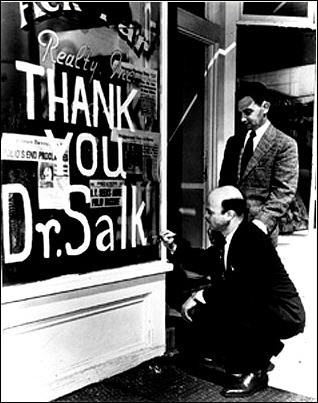

On April 12, 1955, Dr. Thomas Francis Jr., who monitored the Salk trials, called a press conference at the University of Michigan. The conference was broadcast to to 54,000 physicians who gathered in movie theaters; millions of Americans tuned in by radio. After Francis declared Salk’s vaccine to be “safe and effective,” church bells rang out and tearful families embraced. The polio panic would soon be over, as pharmaceutical companies rushed to create hundreds of millions of doses of the new vaccine.

Sabin’s Europeans trials were also deemed highly successful, and in 1957, his oral vaccine was tested in the United States. In 1963, it became the standard vaccine, and the one used in the effort to eradicate polio around the world. There has always been, with Sabin’s vaccine, a slight chance that the polio virus could mutate back into a dangerous virus—a risk the United States deemed unacceptable. A federal advisory panel recommended Salk’s killed-virus vaccine for use in Americans.

Over the years, polio was found to be a highly contagious disease that spread, not in movie theaters or swimming pools, but from contact with water or food contaminated from the stool of an infected person, and yet polio panic was a source of anxiety among Americans surpassed only by fear of atomic attack. Although Jonas Salk is credited with ending the scourge of polio because his killed-virus vaccine was first to market, Albert Sabin’s sweet-tasting and inexpensive oral vaccine continues to prevent the spread of poliomyelitis in nearly every corner of the world.

Sources

Books: David M. Oshinsky, Polio: An American Story, Oxford University Press, 2005. Jeffrey Kluger, Splendid Solution: Jonas Salk and the Conquest of Polio, Berkley Trade, 2006.

Articles: “Jonas Salk and Albert Bruce Sabin.” Chemical Heritage Foundation, www.Chemheritage.org. ”Conquering Polio,” by Jeffrey Kluger, Smithsonian magazine, April, 2005. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/polio.html ”Fear of Polio in the 1950s,” by Beth Sokol, University of Maryland, Honors Project, http://universityhonors.umd.edu/HONR269J/projects/sokol.html. “Jonas Salk, M.D., The Calling to Find a Cure,” Academy of Achievement: A Museum of Living History. http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/sal0bio-1.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)