Remembering the Alamo

John Lee Hancock’s epic re-creation of the 1836 battle between Mexican forces and Texas insurgents casts the massacre in a more historically accurate light

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/alamo_alamo.jpg)

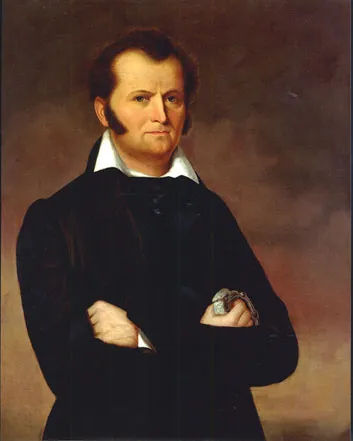

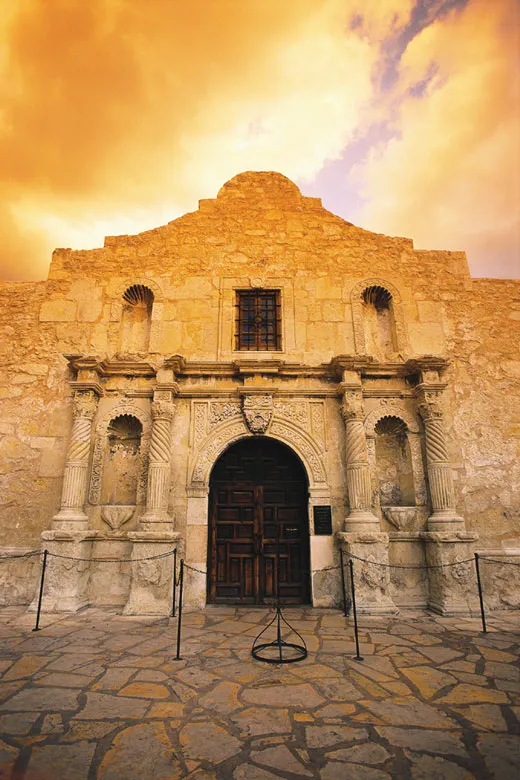

Each year some three million visitors, eager to glimpse a fabled American landmark, converge on a tree-shaded section of downtown San Antonio. In this leafy urban neighborhood, many of them,whether from Berlin or Tokyo or Dime Box, Texas, appear lost. The sightseers glance from their guidebooks to a towering Hyatt Hotel, to the historic 1859 Menger Hotel, to the Crockett Hotel—now that, they may tell themselves, sounds promising—all hard by a drug store, a post office, parking lots and a dingy café serving $5.49 chicken-fried steaks. None of this quite squares with their ideas of the place—largely formed by movie images of John Wayne, eternally valiant in the role of Davy Crockett, defending a sprawling fortress on a vast Texas prairie in 1836. ~ Then tourists round a corner to find themselves facing a weathered limestone church, barely 63 feet wide and 33 feet tall at its hallowed hump, that strikes many as some sort of junior-size replica rather than a heart-grabbing monument. “The first impression of so many who come here is, ‘This is it?’ ” says Although the Alamo defenders including Davy Crockett (played by Billy Bob Thornton, leading a charge, above) fought bravely, the mission complex (in a c. 1885 depiction of the garrison) was nearly indefensible. General Santa Anna, commander of the Mexican Army, called it an irregular fortification hardly worthy of the name.. historian Stephen L. Hardin. “Of course, they’re looking only at the church, not the entire Alamo,” he says of the old Spanish mission that became an unlikely fortress. (The word Alamo means “cottonwood” in Spanish. The mission, established in 1718 and erected on this site in 1724 near the San AntonioRiver, was bordered by stands of poplars.) “It does seem dwarfed by surrounding hotels. I overhear people all the time saying, ‘It’s so small.’ ”

Small it may be, but the “shrine to Texas freedom” looms large in the annals of courage. With the release this month of the new movie The Alamo, filmgoers far too young to remember the 1960 epic, an outsize drama showcasing Wayne as the bold frontiersman Crockett—or actor Fess Parker’s portrayal of a coonskin-capped Crockett on the 1954-55 Disney television series of that name—may discover anew the dramatic power of a uniquely American saga. In this case, the heroic triumvirate of Alamo defenders—William B. Travis, James Bowie and David (as he called himself) Crockett—are portrayed, respectively, by Patrick Wilson, Jason Patric and Billy Bob Thornton.

By no means a remake of Wayne’s histrionic chronicle—“there was hardly a line of historically accurate dialogue in it,” says North Carolina State University historian James E. Crisp—the new, $90 million film from Texas-born director John Lee Hancock is a graphic and largely factual rendition of the legendary battle between insurgent Texas settlers and the Mexican Army.

For many Americans, the actual confrontation remains a symbol of the courage of ordinary men placed in extraordinary circumstances. Others see it as emblematic of America’s territorial ambitions in an era of Manifest Destiny.

Andres Tijerina, a historian at Austin Community College, recalls the day in 1958 at Edison Junior High in San Angelo, Texas, when his history teacher finished her lesson on the Alamo by glaring at him, a kid who, like countless American youngsters, was hooked on the Fess Parker TV series and longed for a coonskin cap. “You’re a Mexican,” she said to Tijerina, even though he was a third-generation U.S. citizen. “How do you explain what they did to Davy Crockett?”

“That was the last time,” says Tijerina, “that I ever wished for a coonskin cap.”

“The Alamo became a hammer for bashing Mexican-Americans in Texas,” says Crisp, a Yale-educated Texan. “It was portrayed as a race war” between Mexicans on one side and American settlers thirsting for freedom on the other. But “on that battlefield there were free blacks, slaves, Indians from central Mexico who spoke no Spanish, Tejanos [Mexicans who sided with the Americans], Europeans, including an Italian general . . . It was almost a laboratory in multiculturalism. It was not a race war.”

All kids growing up in 1950s Texas—as I did—were raised on textbooks that omitted or obscured the fact that the Alamo counted among its defenders Spanish-speaking, Mexican-born Tejanos who fought bravely. “They are the people who often get erased from the story of Texas independence,” says Crisp, who appeared in a recent PBS documentary on the role of Tejanos in the Texas Revolution. “They had their own reasons to fight for Texas independence. This Anglo-Mexican cooperation was purged from the Alamo myth.” Textbooks of the time also neglected to mention that many Alamo heroes, foremost among them Travis and Bowie, had been slaveholders, even slave traders, or that one account of the 12-day Alamo siege, and lightning-quick battle on the 13th day, came from a defender who survived—Travis’ slave, a 23-year-old African-American man known to history only as Joe.

“Telling this tale is an awesome responsibility,” director Hancock, 47, told me in his trailer during the final days of filming last summer. A graduate of Baylor Law School and a screenwriter, Hancock presided over 101 production days that saw Central Texas temperatures go from 22 degrees in January to 102 degrees in August. “I feel the burden of this film in a good way,” he says. “I want to please myself, but I also want to please that 8-year-old in the audience who might make his first trek to the Alamo holding the hand of his grandmother—just as I did.”

Hancock says his intention was to convey depth and humanity upon Mexican soldiers while portraying Travis, Bowie and Crockett less as freedom’s icons than as mortal, fallible men trying to do their best in a difficult situation. Yet Hancock recoils at the suggestion that the movie might be viewed as an exercise in political correctness. “If I had deliberately set out to tell only ‘the Mexican side,’ it would have ended up on the editing room floor,” he says. “Santa Anna may be the most fascinating guy in the movie, and I can’t deny an attempt to convey that a very large Anglo constituency [at the Alamo] was interested in keeping slavery, but ultimately, I looked for those things that would tell the very best story. . . . The facts of the Alamo are far more interesting than the mythology.”

Mexico had a marketing problem. Soon after gaining independence from Spain, in 1821, the young republic desperately wanted to populate its northern state, Texas, to solidify its grip on a huge, lawless territory that the Spanish had never effectively colonized. But few “interior” Mexicans south of the Río Grande wanted to move to the Texas province, largely because it was inhabited by Apaches and Comanches, who were not looking for neighbors. So Mexico offered U.S. settlers cheap land—on the condition they swear allegiance to Mexico and convert to Catholicism. (A good many settlers no doubt failed to abide by those conditions.) Ultimately, says historian William C. Davis, “the Anglos would pose a greater threat than ever the Comanches had.”

Not only did the Mexican government offer land grants to any person or family who agreed to settle in Texas; it also, under the Mexican Constitution of 1824, guaranteed that newcomers would pay no taxes for at least seven years. And to sweeten the deal, Mexico—despite having abolished slavery in the republic—would allow Anglo settlers to bring along with them any slaves they already held.

Before long, immigrants were arriving from nearly every state east of the Mississippi, as well as from France, Germany, Ireland, Denmark, England and Scotland. Edwin Hoyt, author of The Alamo: An Illustrated History, writes that typical settler Dr. Amos Pollard, a New York City physician with a failing practice, awoke one morning in 1834, read an advertisement for land in Columbia, Texas, and set out almost immediately to claim some for himself. Pollard, who would die at the Alamo, where he had served as doctor, settled alongside blacksmiths and trappers from Tennessee, an Irish artist, a Frenchman who had served as a soldier in Napoleon’s army and jailbirds from Alabama. Most of the newcomers, according to Hardin, were “descended from America’s first revolutionaries, and many had fought with Andrew Jackson in 1815 at New Orleans” against the British.

Among those headed for the new frontier was Moses Austin, a Connecticut-born mining magnate, judge and slaveholder from the MissouriTerritory who had received permission from Mexican officials in San Antonio to bring 300 families with him. Although he contracted pneumonia and died in 1821 before he could lead settlers to Texas, his son Stephen succeeded in transplanting the first of some 1,500 families. Today, of course, the capital of Texas bears the Austin name.

By 1834, only 31 years after the United States had doubled its territory with the Louisiana Purchase, tens of thousands of Americans had come to Texas, a place portrayed in newspapers back East as a land of milk and honey with boundless forests and “smiling prairies [that] invite the plough.” (Understandably, there was no mention of scorching summers or lowlands infested with disease-carrying mosquitoes.)

Some settlers, however, had come to Texas uninvited, and before long, the fledgling republic of Mexico was viewing the newcomers warily: by 1830, Americans in Mexico outnumbered Mexicans almost five to one. Although the Mexican congress prohibited further immigration from the United States in April of that year, squatters continued to pour in. Four years later, Mexico ordered the removal of all illegal settlers and the disarming of Texians, as the Americans called themselves (the term would later be contracted to Texans). The man behind the order was a handsome egotist and power-crazed dictator who called himself the Napoleon of the West: President-General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Tensions leading to this order had mounted in the preceding year. In 1833, Stephen Austin rode to Mexico City to urge the government there to confer separate statehood, within the Mexican confederation, on Texas. The Mexican government, not surprisingly, evinced little enthusiasm for such an arrangement. Austin then fired off an intemperate letter to friends in San Antonio, telling them to ignore the authority of Mexico City. Austin’s letter was intercepted; as a result, he was thrown into jail in Mexico City for 18 months. Austin returned home convinced that his fellow colonists had to resist Santa Anna, who had already developed a reputation as a brutal man who sanctioned rape and mass executions by his soldiers.

Within two years, the Mexican congress had authorized Santa Anna to take up arms against the insurrectionists. On November 12, 1835, Texas chose the brilliant but dissipated Sam Houston, who had served under Jackson and had been former governor of Tennessee, as its commander. Santa Anna, lusting for a fight, departed central Mexico in late December. By January 1836, Texians were hearing rumors that the president-general and some 6,000 men were headed their way to teach them a lesson.

In the year leading up to the battle of the Alamo, a number of small but significant skirmishes between settlers and Mexicans had taken place, one of the most important of which was the Texians’ virtually bloodless capture, on December 9, 1835, of the Alamo itself, then a crumbling three-acre mission under the command of Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cós. Says historian Davis, “The Texians kept Mexican arms because they needed them, and allowed Mexican prisoners to go home because they would have been a drain on Texian resources if kept as prisoners.”

By early February 1836, Travis, Bowie and Crockett, three volunteer soldiers, had come to San Antonio to join the struggle for independence. Bowie, fleeing his own checkered past, had arrived in Texas from Louisiana in the late 1820s. In league with his brother Rezin (said to have designed the knife that bears the family name), Bowie, a former slave smuggler, had masterminded a complex series of failed Louisiana land swindles; he had hoped to recoup his fortune by speculating in Texas acreage. He was, says Hardin, “a bit of a thug.” But Bowie possessed virtues as well: a born leader, he was utterly fearless and he outwitted the enemy from the moment the Texians began skirmishing with Mexican regulars. He spoke and wrote fluent Spanish and maintained close friendships within the Tejano community: in 1831, he had married the daughter of a prominent Tejano family from San Antonio; his young wife had died of cholera in 1834. At the Alamo, Bowie would take command of the volunteer company.

William B. Travis was Bowie’s opposite. Bookish, regimented and something of a prig, he had begun to build a law practice in the Texas town of Anahuac. He had acquitted himself well in a clash with the Mexicans in that settlement, participated in the taking of the Alamo and accepted a commission there, assuming responsibility for the formerly enlisted men, or regulars. At the final Alamo battle he would confront the first wave of attackers.

Of the three men, Crockett was the most charismatic. “He was probably America’s first celebrity,” says Hardin of the three-term Tennessee congressman and frontier hero, a renowned marksman and tracker who had served under Jackson in the Creek War of 1813-14, a campaign against Alabama’s Indian tribes. “He came into the Alamo, and these hardened men surely stopped and said, ‘My God, there’s a living legend.’ He was the one you’d want to invite over for dinner—sort of a cross between Will Rogers and Daniel Boone.”

Born in 1786, Crockett had played hooky from school and run away from his Tennessee home to escape his father. He began his military-political career in his mid 20s and was elected to his first Congressional term in 1827. Within a few short years he would become the subject of tall-tale biographies. Like politicians of today, he penned a memoir that was meant to launch a presidential campaign—against Andrew Jackson in 1836—but that plan was derailed when he lost his bid for a fourth Congressional term in 1835. It was then that he decided to go to Texas, where he would write to friends that he had reached “the garden spot of the world.”

“Crockett had real wisdom,” says Hardin. “The more you learn about him, the more you like him.” Along with a handful of companions—fellow Tennesseans who also had once served under Jackson—Crockett set out for the Alamo looking for adventure. “It was pure chance that brought him there,” says Davis. Crockett quickly became a favorite among the men.

On March 2, 1836, some 59 insurgents, Houston among them, convened in Washington-on-the-Brazos and issued a manifesto declaring Texas’ independence from Mexico—however unprepared the settlers may have been for the consequences of such an action. “Most people don’t realize how disorganized the Texians were,” says Crisp. “The ambitions and egos of those would be commanders disrupted any orderly command structure. And this whole independence thing was thrust on them way before they were ready.”

In stark contrast to the motley Texians, Santa Anna’s cavalry men wore dark blue “coatees” with white metal buttons and blue campaign overalls with a red, leather-reinforced seam stripe, and helmets festooned with a comb of black horsehair. They were armed with lances, sabers, short-barreled infantry muskets and the Pageant carbine, a British surplus rifle.

But the cavalry’s sartorial grandeur could not disguise the fact that many of Santa Anna’s conscripted soldiers were Indians pulled from their villages for an agonizing march north through the record-setting cold winter of 1836. “Mules and soldiers were freezing to death,” says Hardin. The hapless soldiers wrapped rags around their feet and packed grass and hay inside the rags.

When they were not fighting frostbite and disease, the men endured repeated attacks from Comanches, who raided them for muskets, blankets and food. With no idea who they would be battling and no combat experience, these shabby, half-starved peasants hardly inspired fear.

Once they reached San Antonio on February 23, many of Santa Anna’s officers were baffled as to why the general seemed so eager to attack, rather than waiting on more artillery. “Santa Anna constantly overplays his hand,” says Hardin of a character flaw that even the general himself recognized. “He once said, ‘If I were to be made God, I would wish for more.’ ” Santa Anna ordered the fort bombarded by cannon. Inside, the fewer than 200 Texians grew anxious. Ominously, the general had raised a blood-red flag, signifying that no quarter would be given. Crockett did his best to keep up spirits, playing tunes on his fiddle.

It is doubtful that the music soothed Travis, the garrison’s intense 26-year-old commander. “The John Wayne film made Travis out to be sort of foppish and prissy,” says Hardin, “but he wasn’t that way at all. He didn’t drink, which was rare back then, but he would buy everyone else drinks. He just wanted to avoid failure at all costs.”

In a letter of February 24, Travis called on the “People of Texas and all Americans in the world” to send reinforcements: “I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna!” he wrote. “I have sustained a continual Bombardment & cannonade for 24 hours & have not lost a man. The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion [meaning the safety of surrendered men would not be guaranteed], otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken. I have answered the demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls. I shall never surrender or retreat. Then, I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism & every thing dear to the American character, to come to our aid with all dispatch. The enemy is receiving reinforcements daily & will no doubt increase to three or four thousand in four or five days. If this call is neglected, I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible & die like a soldier who never forgets what is due his own honor & that of his country. Victory or Death.”

Travis had already appealed to Col. James W. Fannin, a West Point dropout and slave trader who had about 300 men and four cannon, but little ammunition and few horses, at the Spanish presidio at Goliad, some 100 miles away. Fannin set out for San Antonio on February 28, but three wagons broke down almost immediately, and crossing the flooded San AntonioRiver consumed precious time. When the men made camp, they neglected to tie up their oxen and horses, many of which wandered off in the night.

Fannin returned to Goliad, where he ignored additional pleas from Travis. “Fannin was just in over his head,” says Crisp. Fannin would later fight bravely and would ultimately die at the hands of Santa Anna’s troops. “But he would have been nuts to go to the Alamo,” Crisp adds.

Santa Anna must have known the Alamo would be no match for his forces. Built by Spanish priests with Indian labor, the mission was never meant to be a fortress. Lacking extended walls or rifle parapets, it was almost impossible to defend—not because it was too small but because it was too big. Its main plaza, now hidden beneath downtown San Antonio’s streets, comprised almost three acres, with nearly a quarter-mile of adobe walls that were scarcely cannon-proof and easily scaled with ladders—an “irregular fortification hardly worthy of the name,” sniffed Santa Anna.

The morning of March 3 brought bad news. Travis’ trusted subordinate, James Bonham, rode in from Goliad with word that Fannin would not be coming with help. Then, on March 4, one thousand fresh Mexican soldiers arrived from the west. “Take care of my little boy . . . ,” Travis wrote to David Ayres, a friend who was keeping his son. “If the country should be lost and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.” Travis also wrote to the insurgent settlers assembled in Washington-on-the-Brazos: “I will. . . . do the best I can under the circumstances . . . and although [my men] may be sacrificed to the vengeance of a Gothic enemy, the victory will cost the enemy dear, that it will be worse for him than defeat.”

By March 5, Mexican troops were lashing ladders against the fort’s walls in preparation for an assault, and according to the account of Mexican general Vincente Filisola, the besieged men dispatched a woman to propose terms of surrender to Santa Anna. Once again Santa Anna refused to negotiate terms. His decision was purely political, says Hardin. “Militarily, it was stupid: storming the Alamo needlessly sacrificed the lives of hundreds of men. But Santa Anna wanted to be able to write back to Mexico City that he had annihilated the rebels.”

Documentary accounts of the final battle, on March 6, are based largely on journals of Mexican officers and the stories of a few noncombatant survivors who had sheltered inside the Alamo. At about 5:30 a.m., some 1,100 of Santa Anna’s men moved quietly under patchy bright moonlight to surround the garrison. Some of the general’s young soldiers were so excited they could not maintain silence. Viva Santa Anna! they shouted. Viva la Republica! Their cries alerted the Alamo’s defenders. “Come on, boys,” Travis shouted as he sprinted to the walls, “the Mexicans are upon us, and we’ll give them hell!”

The Texians filled their cannons with every available piece of metal—hinges, chains, nails, bits of horseshoes—and sprayed deadly shot over their tightly bunched attackers, who carried axes, crowbars, ladders and muskets fixed with bayonets. The Texians’ nine-pound cannonballs inflicted heavy casualties, splattering flesh and jagged bones over soldiers who were not themselves hit. The carnage caused some Mexicans to attempt retreat, but officers forced them back into battle at swordpoint.

The wounded shrieked in agony, some begging to be put out of their misery. “The shouting of those being attacked . . . ,” wrote Lt. Col. José Enrique de la Peña, “pierced our ears with desperate, terrible cries of alarm in a language we did not understand. . . . Different groups of soldiers were firing in all directions, on their comrades and on their officers, so that one was as likely to die by a friendly hand as by an enemy’s.” At the Alamo’s 12-foot north wall, the Mexicans felled Travis with a musket ball to the forehead. Then Santa Anna sent in more troops, bringing the assault forces to nearly 1,800. Within about half an hour, the Texians retreated toward the barracks and chapel, hemmed in hopelessly for one last, bloody stand.

“Great God, Sue, the Mexicans are inside our walls!” screamed Capt. Almaron Dickinson to his wife, Susanna. “All is lost! If they spare you, save my child.” Susanna and her infant daughter, Angelina, took shelter in the church’s sacristy, along with several Tejano women and children, all of whom, in addition to several unidentified Texian slaves, Santa Anna would spare.

In the Alamo’s final minutes, the fighting turned to hand-to-hand combat with knives, swords and bayonets. Some Texians tied white cloths to bayonets and thrust them through the broken walls, screaming their wish to surrender in whatever Spanish they could command. Historian Alan Huffines believes as many as 50 defenders, not accounted for in the oft-cited number of 189 killed, fled the Alamo over the low east wall, only to be slaughtered by Mexican lancers positioned outside the fortress. (Stricken by what is now thought to be typhoid pneumonia, delirious and probably near death, Bowie was slain in his bed.)

Finally, using cannons they had captured from the defenders, the Mexicans blasted open the entrance to the chapel and butchered the last defenders, except, many historians believe, for Crockett and perhaps a half dozen of his men, who may have been taken alive. In this scenario, Gen. Manuel Fernandez Castrillón wanted to spare the men. But according to de la Peña’s account, when Santa Anna finally entered the Alamo, he ordered their immediate execution. In the end, says Davis, “We don’t know where or how Crockett died, and we never will.”

Santa Anna ordered the bodies of all the Texians heaped onto grisly pyres, inside and outside the Alamo, and set afire. “The bodies,” wrote de la Peña, “with their blackened and bloody faces disfigured by desperate death, their hair and uniforms burning at once, presented a dreadful and truly hellish sight.”

Although the idea that the Alamo defenders refused even to contemplate surrender is an article of faith for many people, Crisp says “it is just a myth that they pledged to die no matter what. That’s the myth that is pervasive in the Fess Parker and John Wayne versions. But these were brave guys, not stupid [ones].”

In the aftermath of the battle, Texians exaggerated Mexican casualties while Santa Anna underreported them. Historian Thomas Ricks Lindley, author of Alamo Traces, used numerous Mexican sources to conclude that Mexican fatalities were about 145 on March 6, and that 442 Mexicans were wounded during the entire siege. Other research suggests as many as 250 wounded Mexican soldiers eventually died in San Antonio.

As Santa Anna walked among the wounded, many undoubtedly writhing in pain, he is said to have remarked: “These are the chickens. Much blood has been shed, but the battle is over. It was but a small affair.”

Santa anna’s butchery achieved the effect he had sought. Army Capt. John Sharpe described the reaction in the town of Gonzales, which had sent troops to the Alamo, when news of the massacre arrived: “Not a sound was heard, save the wild shrieks of the women, and the heart-rending screams of the fatherless children.” Many Texas families soon pulled up stakes and fled eastward.

Forty-six days after the fall of the Alamo, however, Santa Anna met his match. The general, flush with a second major victory at Goliad, where he slaughtered Fannin and his some 350 men but lost many of his most experienced fighters, marched east with about 700 troops (later reinforced to 1,200) toward present-day Houston. He camped on high ground at San Jacinto.

But Sam Houston and a force of about 900 men had gotten there first. By April 21, Santa Anna’s troops were exhausted and hungry from their march. “They had probably gone two days without sleep,” says Hardin. “Many just collapsed in a heap.”

At about 3:30 p.m., the Texians hurtled through the brush, bellowing, “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!,” killing unarmed Mexicans as they screamed, Mi no Alamo! Mi no Goliad! A Mexican drummer boy, pleading for his life, was shot point-blank in the head. “There were atrocities committed every bit as odious as at the Alamo,” says Hardin. Houston’s official report says the San Jacinto battle lasted a mere 18 minutes and claimed 630 Mexican lives, with 730 taken prisoner. The Texians lost nine men. Santa Anna escaped, disguised as a common soldier, but was captured the next day. The Texians had no idea who he was until some Mexican prisoners addressed him as El Presidente. In a remarkable face-to-face encounter, Sam Houston, who intuited that the dictator was more valuable to the fledgling republic alive than dead, negotiated with him for an entire afternoon. Santa Anna saved his skin by agreeing to sign a treaty guaranteeing Texas’ independence from Mexico. He was held in custody—documentation is scanty about the length of his incarceration—and within two years allowed to return to Mexico. Remarkably enough, he would manage to ascend to the presidency three more times.

In the end, says director Hancock, dispelling some of the mythology that has grown up around the Alamo does not demean the men who endured the siege and final assault. “By owning up to these men’s pasts, they become more human and their bravery and sacrifice all the more compelling,” he says. “I’ve always been attracted to flawed heroes.”