These Rare Photos of the Selma March Place You in the Thick of History

James Barker, a photographer from Alaska, shares his memories of documenting the famed event

James Barker was a technical photographer, working with Washington State University's Division of Industrial Research in Pullman, Washington, when he received an unexpected phone call from a colleague: the university had pulled emergency funds together to send three representatives to Selma, Alabama, in anticipation of the third march organized by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The WSU group would join tens of thousands of others from around the country, compelled to join King and civil rights marchers after the violent outcome of the first march, dubbed Bloody Sunday, had left 17 marchers injured at the hands of state and local police. Barker, who spent his weekends and vacations conducting photographic studies of people (migrant workers in Yakima, for instance, or a redevelopment area in San Francisco) had been shortlisted. If he were selected to attend the march, his colleague told him, he'd be on a plane that evening bound for the Deep South.

"I was aware of the kind of violence that was pictured of the attempt of the first march, but of course, it was a long ways away," Barker says. "It all happened extraordinarily quickly. The first thing I did [after the call] was go to the refrigerator and see if there was enough film. I was operating in an utter frenzy, wondering what to carry in order to be able to be portable and move very quickly."

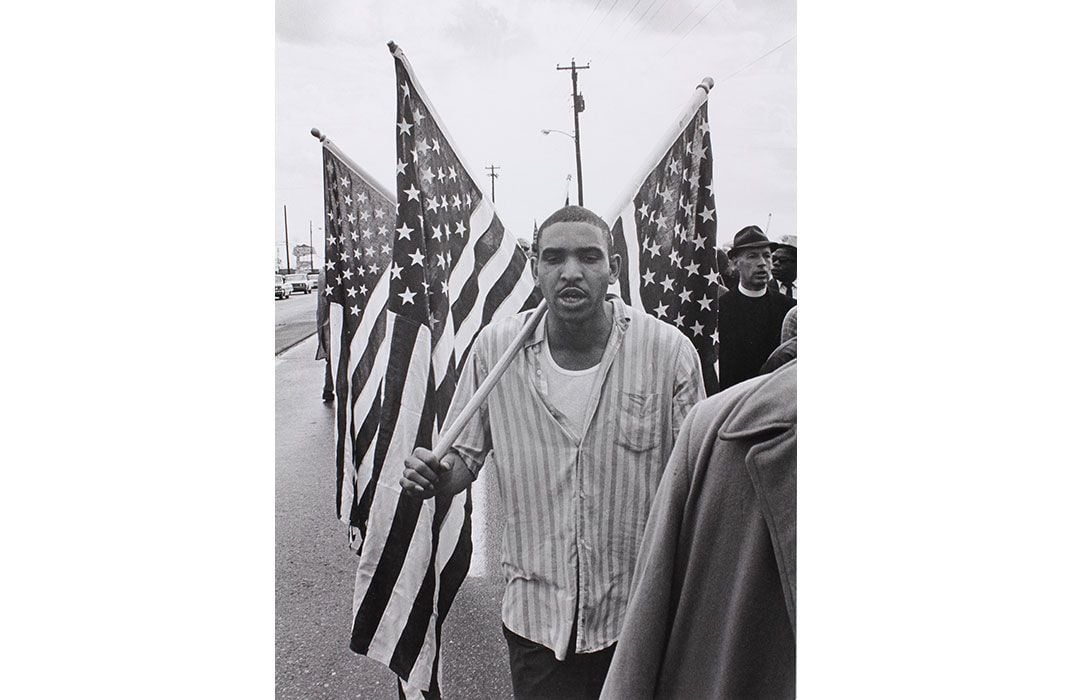

Later that day, Barker found out that he had been selected by the university to travel to Selma. In preparing to head to Alabama, Barker chose his photography equipment carefully, optimizing for simplicity and ease of movement. He took a single Leica with a moderate wide angle lens, which allowed him to take photographs up-close, from inside the march. "My involvement was more of a participant observer, not a press person looking from the outside thinking what kind of story can a photo generate," he says.

Barker and his colleagues arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, the Saturday before the march—which would end up being the third attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery. A pair of volunteers, both black, drove the all-white group from the airport to Selma; throughout the march, volunteers were dispatched to shuttle people (as well as supplies) between Montgomery, Selma and various march sites.

"As we were driving, I was thinking 'When does the photography start?' I looked out of the car at the back and noticed there was a state trooper following us. I pulled out my camera ready to take a photograph, and the driver, who was black, said 'I wish you wouldn't do that, we don't want anything to happen that would prompt them to stop us.' His wife or girlfriend said, 'Those who protect us we fear.'" Barker says. "I thought, 'My god, that's quite a statement.' It's such a different world than what we grew up in on the West Coast."

Barker and his colleagues were taken to Brown Chapel, in Selma, where the march was being organized. He began taking photographs in earnest when they arrived at the chapel and continued to quietly snap photographs throughout the remainder of his time in Alabama, which stretched from the day before the march left Selma to the Wednesday when they reached Montgomery (Barker participated on the first day of the march as well as the last). "Wednesday morning I went out and rejoined the march," Barker says, which had dwindled to 300 people through rural Alabama as per an agreement between organizers and the state. "As I got out of the car, it was an absolute deluge of rain, and here were the thousands of people that had already joined the marchers coming through the rain."

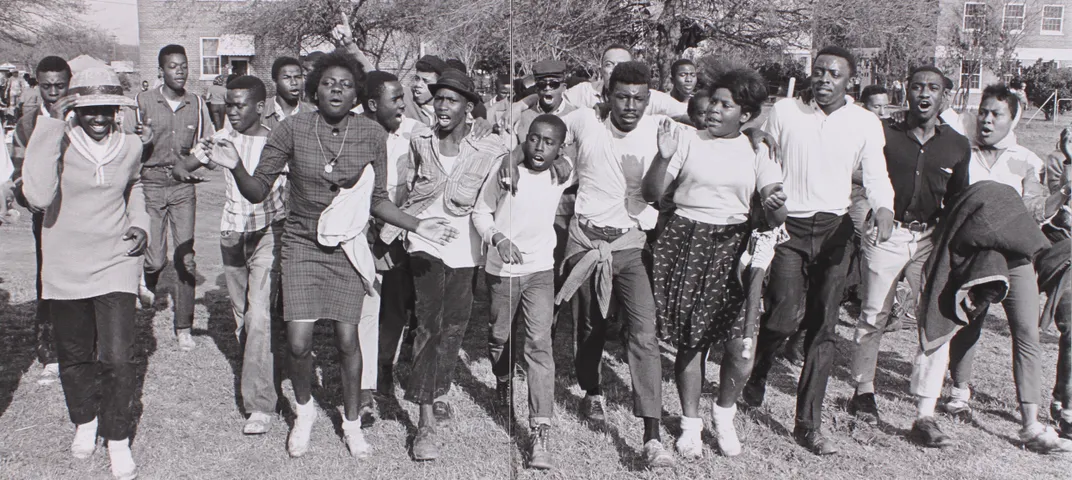

Wednesday night, he snapped his final photograph of the march: a group of teenagers singing. "I really felt that that particular picture of the kids was a highlight of all that had transpired," Barker says.

When he returned to Pullman, Barker immediately processed the film. "I looked at the contact sheets," he says, "and I thought 'Did I really make it? Do I have anything worthwhile?'" The contact sheets sat untouched for over a week, until Barker decided to hurriedly print 74 images, which he hung up in the WSU library. By that time, though, the school year had ended, and the majority of students had left campus.

For years, the photographs traveled throughout the country, hanging on walls of churches and museums. Five years ago, the photographs found their way to the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery, and a few years after that, during a show in Arizona, attracted the attention of a New York art gallery. This March, the photos will head to New York City for a show at the Kasher Gallery.

Nearly 50 years after the march, Barker, who says he is best known today for his photographs of Eskimos in Alaska—took time to answer a few questions from Smithsonian.com.

In photographing the marches and documenting this piece of history, did you have a particular approach in mind? What did you hope to capture in your images?

What I do, through all of my work, is try to carve out personalities of people and interactions—anything possible to show the emotions of who people are and their involvement with each other.

That was the whole attempt. I wasn't conscious of trying to say anything other than 'Here are the people that are involved in this.' During the march there were people on the side standing there glaring at the marchers, and there are a couple of pictures of cars that drove by, and I wanted to cover that hostility so that it shows the environment. But I always just look for who the people are. That has always been my primary goal.

My photographs dwell on individuals, and it takes a number of my pictures for people to understand the message of it.

How did the experience of the march compare with your expectations of how it would be?

When we arrived at Brown chapel, they said that it's safest to remain in that area. That was quite a shock. There was a feeling of this almost kind of utopia of people who were all there with a single purpose in mind, having to do with the march, and yet a few blocks away was this ring where there was a question of safety.

When I was taken up to Montgomery, in the church near the capitol, I looked up and saw the capitol just completely ringed by state police. I didn't leave the church because of the feeling of not knowing what the safety of the environment was; it was real clear I would be seen as an outsider.

As a photographer, how did the people participating in the march react to your presence?

I was operating, as I oft do, as a participant observer. I was there in the middle of the march, carrying a backpack, at times chatting with people, but there were other people there also taking snapshots.

Throughout my life, as I've been photographing situations, something has happened that I really can't entirely explain. Often, I'll be photographing in an event, and when people see the pictures, they'll say, 'This is amazing, I didn’t even know you were there.' I’m 6'2, it's a little surprising that I can mill around in the middle of people and photograph people rather closely and intimately without their seeming to know that I’m there.

I try to work very quickly, capturing moments of interaction and expression, but at the same time, purposely try to avoid making eye contact. If you don't make eye contact, people don't seem to be aware that you're there.

The whole thing was just to be in the middle of a crowd of people and photograph, and not in any way to intrude.

Decades after the march—the movie Selma has come out, there have been more contemporary marches dealing with more recent injustices foisted upon black communities in America—what can we learn from looking back at this moment in these photographs?

Two summers ago, I decided to reprint the exhibit, because it's been recognized that the original prints have considerable historic value, and we decided that we would never exhibit them again. I was reprinting the exhibit in the middle of the summer at the time when the Supreme Court decision came down and gutted one of the major parts of the Voter's Rights Act, and immediately states—including Alabama—changed their laws, which in effect becomes voter suppression.

All I feel I can do is try to put the human element into this—who the people are, that they’re not anonymous people that were very much involved in the march and the demonstrations. Just trying to humanize the whole thing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)