Pioneering Social Reformer Jacob Riis Revealed “How The Other Half Lives” in America

How innovations in photography helped this 19th century journalist improve life for many of his fellow immigrants

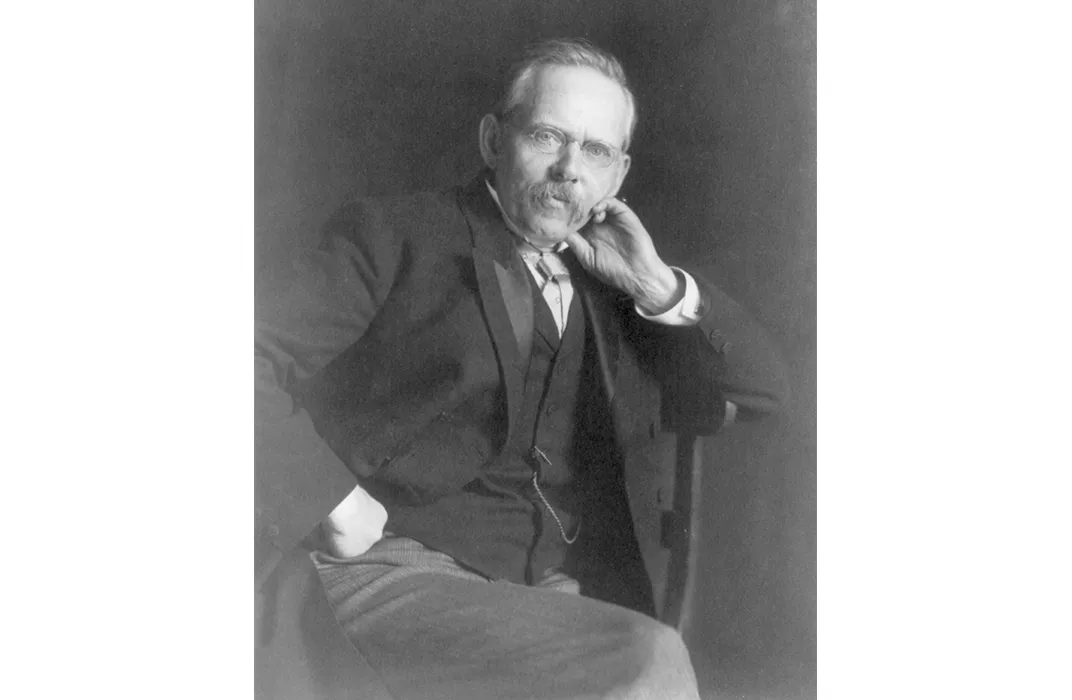

In 1870, when Jacob August Riis immigrated to America from Denmark on the steamship Iowa, he rode in steerage with nothing but the clothes on his back, 40 borrowed dollars in his pocket, and a locket containing a single hair from the girl he loved. It must have been hard for the 21-year-old Riis to imagine that in just a few short years, he would be pallin’ around with a future president, become a pioneer in photojournalism, and help reform housing policy in New York City.

Jacob Riis, who died 100 years ago this month, struggled through his first few years in the United States. Unable to find a steady job, he worked as a farmhand, ironworker, brick-layer, carpenter, and salesman, and experienced the worst aspects of American urbanism--crime, sickness, squalor--in the low-rent tenements and lodging houses that would eventually inspire the young Danish immigrant to dedicate himself to improving living conditions for the city’s lower-class.

Through a little bit of luck and a lot of hard work, he got a job as a journalist and a platform for exposing the plight of the lower class community. Eventually, Riis became a police reporter for The New York Tribune, covering some of the city's most crime-ridden districts, a job that would would lead to fame and a friendship with police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who called Riis "the best American I ever knew." Riis knew what it was to suffer, to starve, and to be homeless, and, though his prose was sometimes sensationalist and even occasionally prejudiced, he had what Roosevelt called "the great gift of making others see what he saw and feel what he felt."

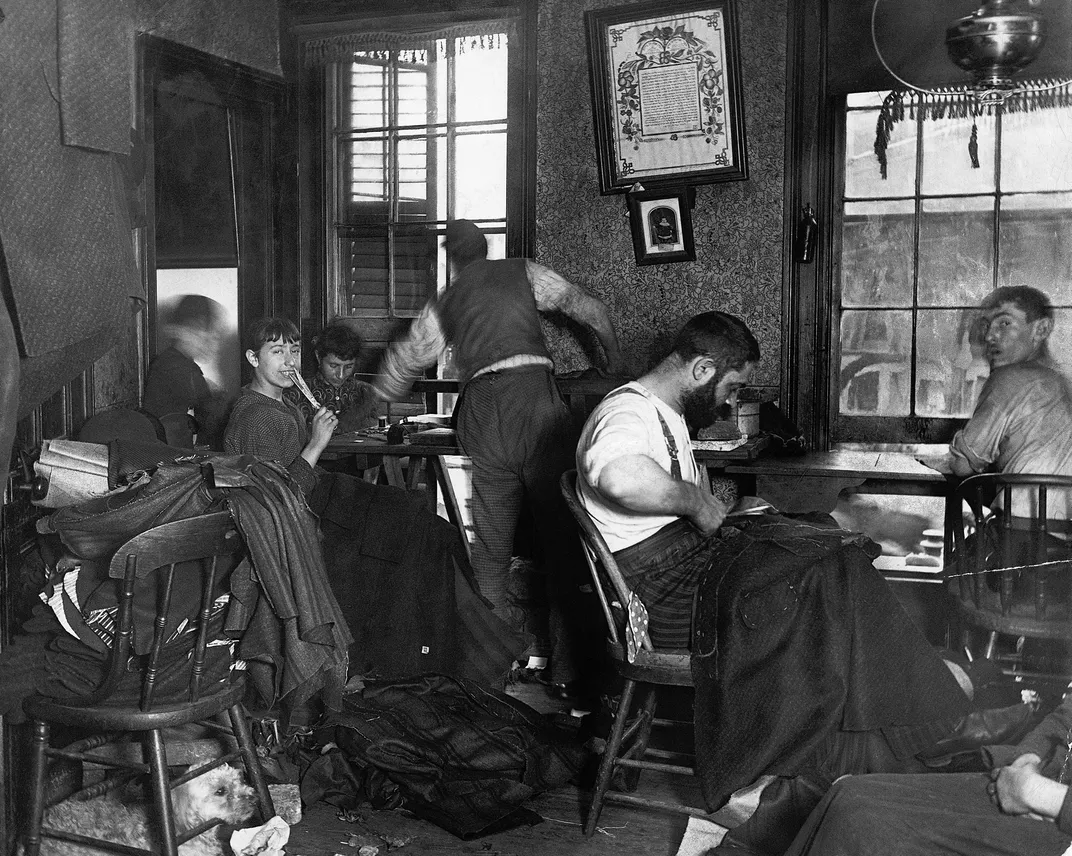

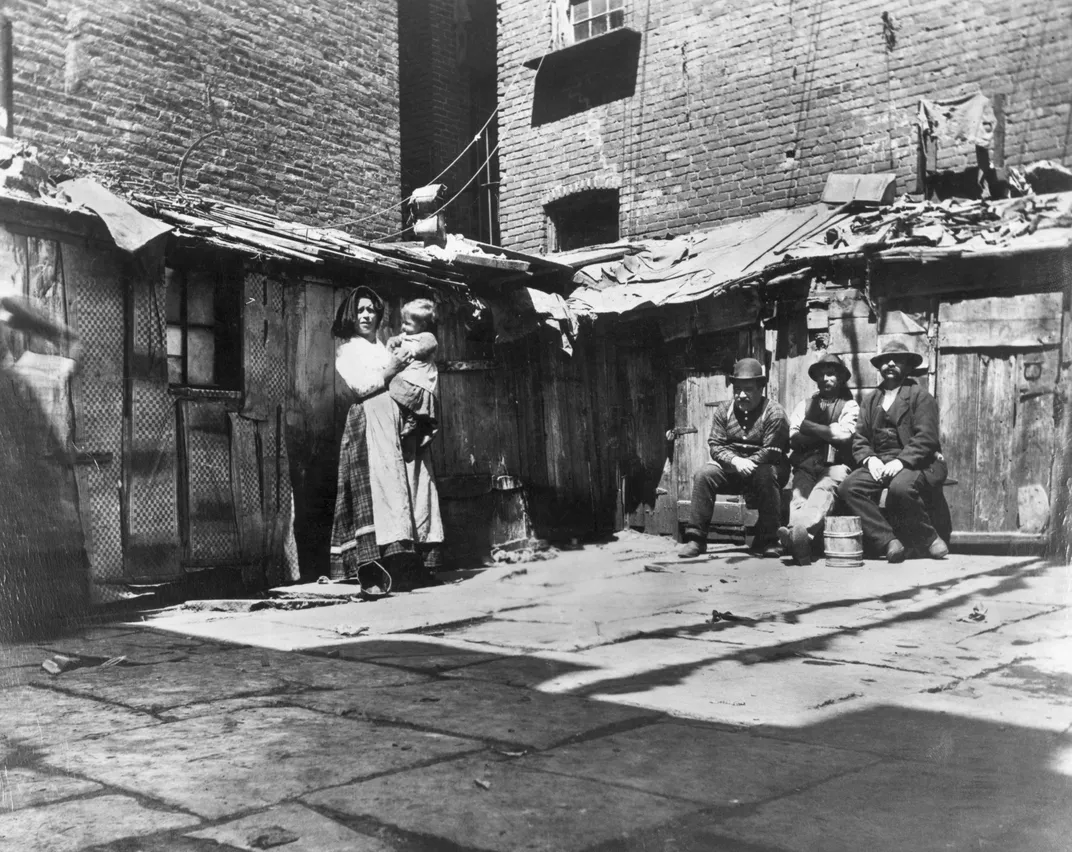

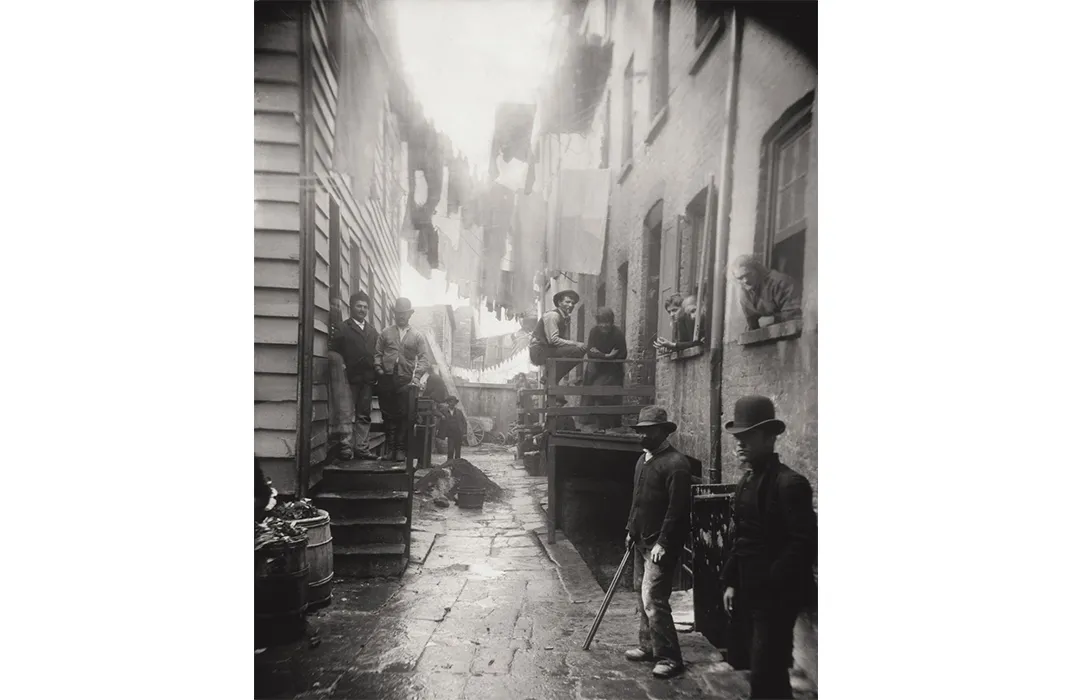

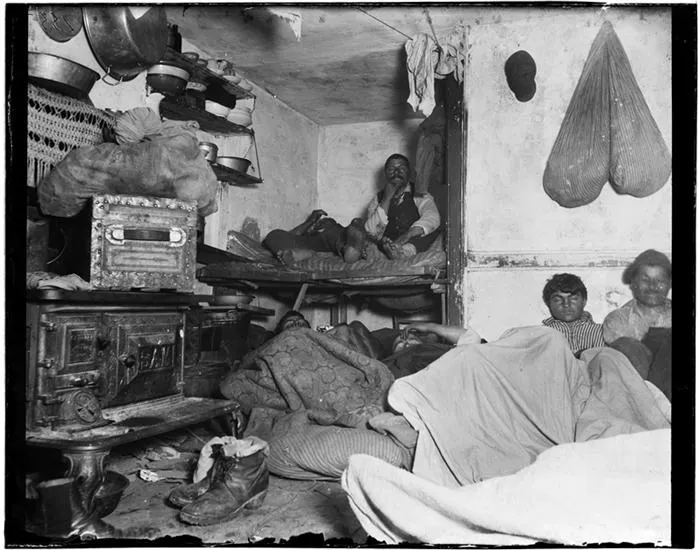

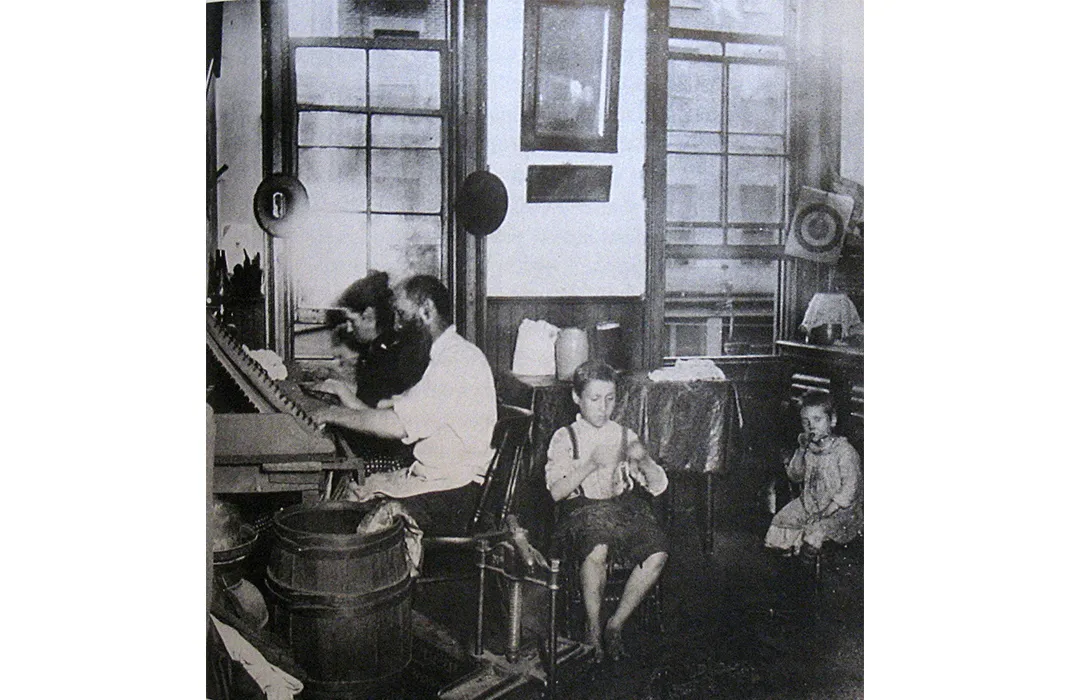

But Riis wanted to literally show the the world what he saw. So, to help his readers truly understand the dehumanizing dangers of the immigrant neighborhoods he knew all too well, Riis taught himself photography and began taking a camera with him on his nightly rounds. The recent invention of flash photography made it possible to document the dark, over-crowded tenements, grim saloons and dangerous slums. Riis’s pioneering use of flash photography brought to light even the darkest parts of the city. Used in articles, books, and lectures, his striking compositions became powerful tools for social reform.

Riis’s 1890 treatise of social criticism How the Other Half Lives was written in the belief “that every man’s experience ought to be worth something to the community from which he drew it, no matter what that experience may be, so long as it was gleaned along the line of some decent, honest work.” Full of unapologetically harsh accounts of life in the worst slums of New York, fascinating and terrible statistics on tenement living, and reproductions of his revelatory photographs, How the Other Half Lives

was a shock to many New Yorkers - and an immediate success. Not only did it sell well, but it inspired Roosevelt to close the worst of the lodging houses and spurred city officials to reform and enforce the city’s housing policies. To once again quote the future President of the United States: “The countless evils which lurk in the dark corners of our civic institutions, which stalk abroad in the slums, and have their permanent abode in the crowded tenement houses, have met in Mr. Riis the most formidable opponent every encountered by them in New York City.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/6a/656af4d0-d828-456a-9863-e94f8f9241b8/be031677.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/39/b9/39b9ef8d-48eb-4c54-8ff9-5821854fc8ae/sf1577.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/5a/a15ac732-5fc2-4437-9177-f547e856e711/ih157172.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/44/5f446967-a5f2-4d9a-adcd-8184c2d32d72/be072639.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/2f/3b2f233f-f6b1-434c-88d4-1aaf8421e52e/be072628.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/30/50301c88-deec-4aca-9946-a10e645a13e6/be072618.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/a4/7fa441cf-f9b7-46ea-a037-9640269556b2/be036609.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ed/5a/ed5a3ae8-6e64-4d8b-9e91-d5d69cc9256b/be031676.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/74/d1/74d1bcfa-6c93-4f08-976f-8ff90fe57176/7-riis-cotton-mill.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/8d/848dc5a9-29d4-4ddb-b953-e7ca65bd16ca/9-riis.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/9e/249e1797-b916-4122-bb1b-932917d5d42a/8-riis-glass-factory.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/a3/1da36bf3-4dd2-4fb1-99e9-b79b3abde77e/6-riis-children.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3f/09/3f09f19b-c12c-4ed6-970c-90bc88cd82fd/5-riis-children-mulberry.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jimmy-Stamp-240.jpg)